Intussusception

Notes

Introduction

Intussusception is the telescoping of intestine into a neighbouring segment, most frequently seen in infants and young children.

It is a common abdominal emergency in infants and young children, typically occurring between the ages of 3 months and 3 years. Patients present with distress and severe abdominal pain often accompanied by vomiting and bloody stools.

The mesentery of the telescoped segment of intestine is impaired leading to reduced venous and lymphatic outflow. Intestinal oedema, obstruction and ischaemia develop.

Early diagnosis and appropriate management are essential to obtaining good outcomes. The majority of patients can be managed with non-operative reduction (with air or liquid enema). A proportion of patients, typically with evidence of perforation or who fail non-operative management, require operative intervention.

Epidemiology

Around 80-90% of cases present before the age of two.

Intussusception is rare before 3 months and becomes less common after the age of 2. Though it normally affects young children, up to 10% of cases occur in patients over the age of 5. Males are affected slightly more than females with a ratio of 3:2.

Pathogenesis

Approximately 75% of cases of intussusception in children are said to be idiopathic.

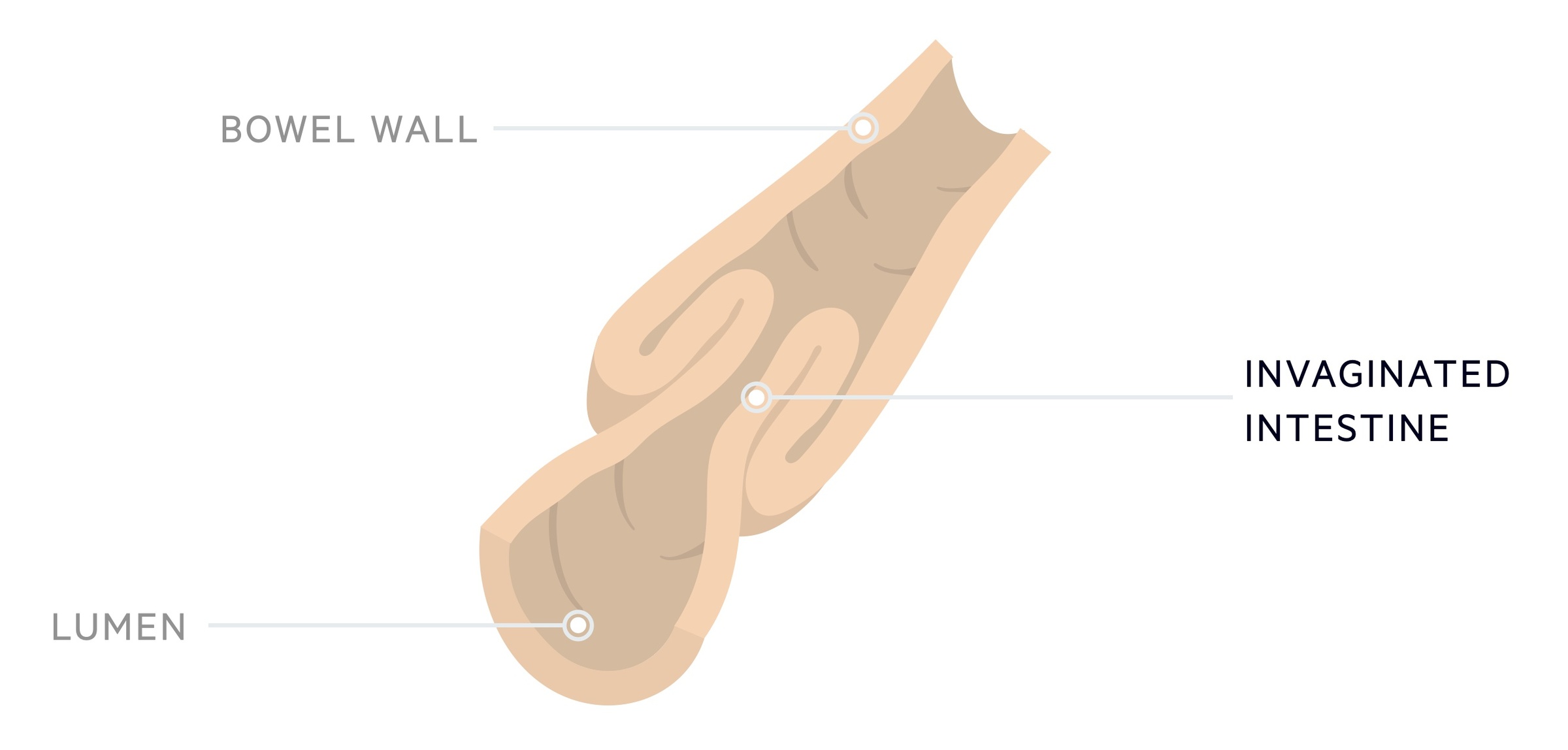

Intussusception occurs when (almost always) a proximal segment of intestine invaginates into a distal segment. There are therefore two components:

- Intussusceptum: the segment of bowel that telescopes into another.

- Intussuscipiens: the neighbouring portion of bowel that receives the intussusceptum.

It can occur anywhere in the intestines but the majority of cases are ileocolic - that is the terminal ileum (the intussusceptum) invaginates into the colon (the intussuscipiens).

The mesentery of the affected segment becomes involved and pressure prevents normal venous and lymphatic drainage. The invaginated segment becomes oedematous and the bowel becomes obstructed. If untreated intestinal ischaemia occurs with resulting perforation and peritonitis.

Cases may be idiopathic (approx. 75%) or secondary to a lead point (approx. 25%). When occurring in older children a higher proportion will have an identifiable lead point.

Idiopathic

In 75% of cases in children no specific cause is identified (i.e. idiopathic). It is thought that viral infections may predispose children to intussusception and children/parents will commonly report recent symptoms consistent with this. It has also been linked to certain types of rotavirus vaccine.

Lead point

In 25% of cases a ‘lead point’ is identified. A lead point refers to an abnormality that predisposes patients to intussusception.

Examples of lead points include:

- Meckel diverticulum

- Vascular malformation

- Lymphoma

- Parasites

- Thick stool (e.g. as seen in patients with cystic fibrosis)

- Polyps

Clinical features

The typical presentation of intussusception involves worsening abdominal pain and vomiting that becomes bilious in a distressed child.

Depending on the severity there may be signs of fluid depletion. Bloody stool is seen in around 50% of cases. The classical red currant jelly stool (blood mixed with mucus and stool) is a late sign and normally absent. The clinical exam may reveal a sausage-shaped mass, often in the right upper quadrant, but again this is often absent.

Patients may also present with a more gradual and insidious onset of symptoms. Some children present with lethargy and signs of systemic upset without significant abdominal pain or bloody diarrhoea.

Symptoms

- Abdominal pain

- Vomiting

- Distress

- Dehydration

- Bloody stool

- Red currant jelly stool (late sign)

Signs

- Sausage-shaped mass

- Abdominal tenderness

- Lethargy

- Dry mucous membranes

- Peritonism (late sign)

Investigations

Abdominal ultrasound offers excellent sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of intussusception.

Bloods

- FBC

- Renal function

- CRP

Imaging

Abdominal X-ray: a soft tissue density may be seen in the right upper quadrant with proximal bowel dilatation. It has a relatively poor sensitivity and specificity and should not be used alone to exclude intussusception.

Ultrasound: USS offers excellent diagnostic sensitivity. The ‘target sign’ is classical for intussusception.

Management

Intussusception in children is often managed with non-operative radiologically guided reduction.

The management of intussusception involves initiating supportive therapies and reducing the invaginated bowel. Here we largely discuss ileocolic intussusception (the most common location in children).

It should be noted, small bowel intussusception (e.g. ileo-ileal, jejuno-ileal, jejuno-jejuno) may resolve spontaneously but where it does not is less likely to resolve with non-operative techniques.

Supportive measures

Children will often be fluid deplete at presentation and will require appropriate IV replacement. A nasogastric tube may be needed. Analgesia should be given for symptomatic relief.

Antibiotics can be given, particularly where there is concern regarding perforation, in line with local guidance.

Non-operative reduction

Stable patients without peritonism or evidence of perforation can normally be managed with non-operative reduction.

The procedure is performed by radiology with the relevant surgical team on standby in case of failure or complication. There are two main techniques:

- Hydrostatic: utilises saline or contrast to resolve the intussusception.

- Pneumatic: utilises air to resolve the intussusception.

The research is somewhat mixed as to which technique is best and both are used in practice. A Cochrane review published in 2017 reflected a relative lack of appropriately powered and reported studies.

Both techniques are conducted under imaging guidance, either sonographic or fluoroscopic. Sonographic requires a hydrostatic technique, whilst either can be guided by fluoroscopy.

Operative intervention

Surgery is typically indicated in patients with evidence of perforation or those that are unstable. It is also required where non-operative reduction fails or is complicated by perforation.

When necessary the procedure can normally be performed laparoscopically allowing diagnosis, reduction and where indicated resection and anastomosis.

Last updated: July 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback