Acute epiglottitis

Notes

Overview

Acute epiglottitis refers to inflammation of the epiglottis and surrounding supraglottic mucosa.

It can be a life-threatening condition due to airway obstruction. Thankfully, acute epiglottitis is now rare in children due to the introduction of the Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib) vaccination as part of the routine immunisation programme. In adults, the incidence is estimated at 1-4 per 100,000 people.

In children, the median age at presentation has increased to 6-12 years (traditionally affected children 2-5 years old). Children who have not been vaccinated are at particular risk.

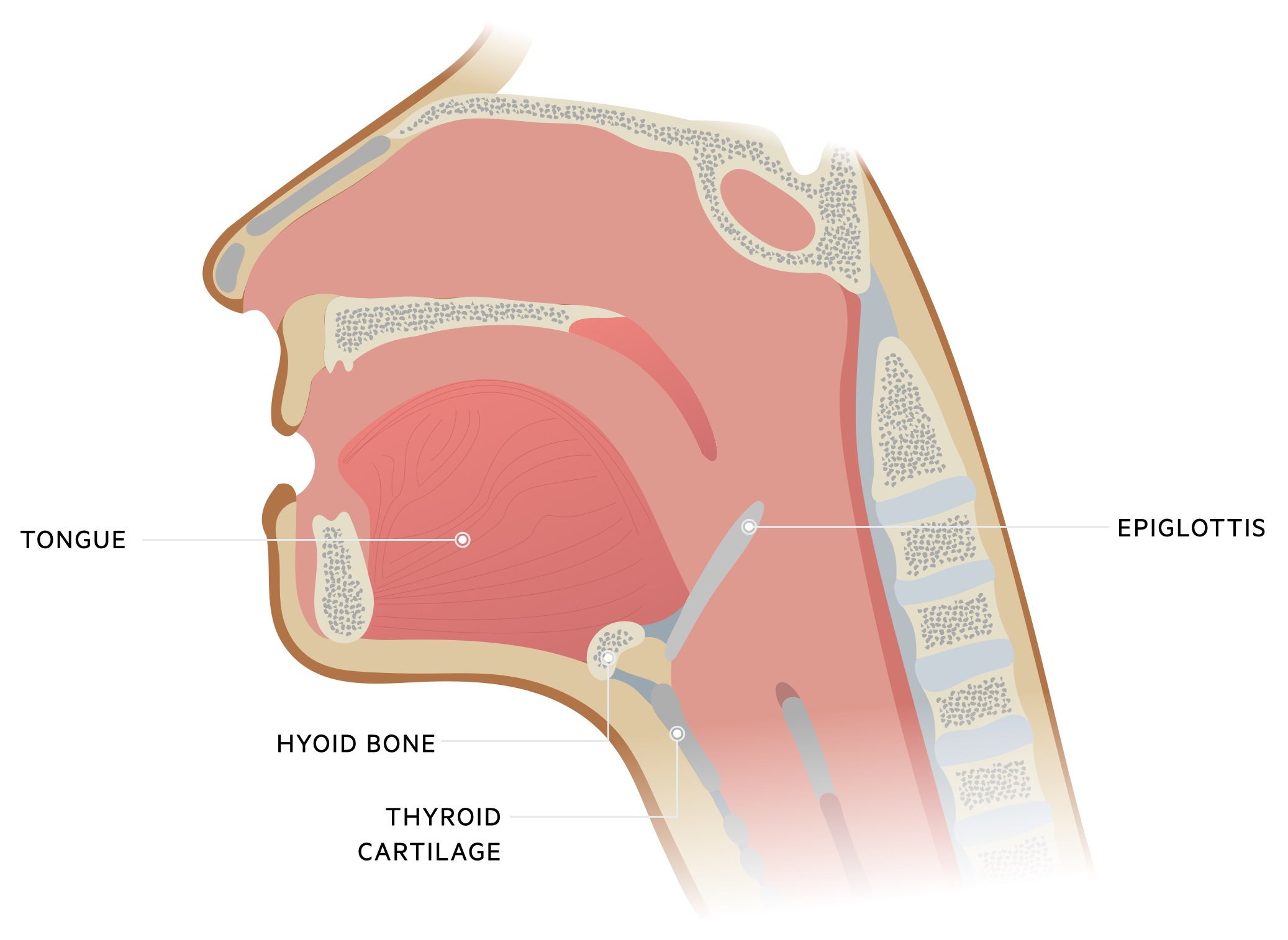

Basic anatomy

The epiglottis is a thin layer of elastic cartilage that sits at the base of the tongue.

It is a leaf-shaped piece of elastic cartilage that protects the airway during swallowing. It contains a layer of stratified squamous epithelium on its anterior surface and superior third of the posterior surface.

Aetiology

Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib) was the classical cause of epiglottitis in children before widespread vaccination was available.

Acute epiglottitis may be caused by a number of infectious microorganisms.

- Bacteria (Haemophilus): Hib most common. Other Haemophilus species (e.g. A, F) can occur.

- Bacteria (Non-Haemophilus): group A Streptococcus, Staphylococcus and Neisseria meningitidis.

- Viruses: human herpes virus, Parainfluenza virus, Influenza B virus.

- Fungal: consider if immunocompromised. Candidia spp. Aspergillus spp.

- Non-infectious: inflammation may occur due to trauma (e.g. thermal injury or ingestion of caustic substances). Other rare causes include graft vs host disease and systemic granulomatous conditions.

Pathophysiology

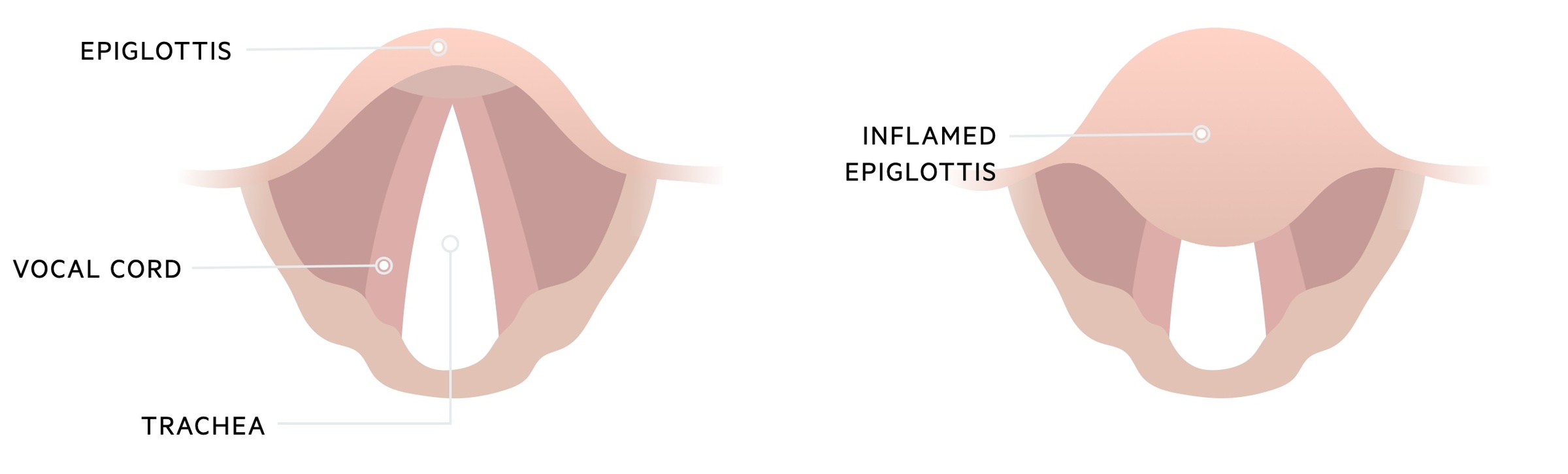

Acute epiglottitis may be due to direct invasion of the mucosal layer by microorganisms.

Infectious microorganisms may lead to acute inflammation of the epiglottitis from direct invasion or spread via bacteraemia. Typically, bacteria (most common cause) reside in the nasopharynx and infiltrate the epiglottis mucosa through defects (i.e. microtrauma).

Defects in the mucosa may occur due to a preceding viral illness or direct trauma from swallowing food. Inflammation and swelling occur and rapidly lead to infection of the entire supraglottic airway leading to potentially life-threatening airway obstruction.

Clinical features

Acute epiglottitis is a medical emergency that can present with severe respiratory distress and stridor.

Children with acute epiglottitis classically present with the three ‘D’s’: dysphagia, drooling, distress (respiratory). Cough is usually lacking (or a less prominent feature) and more characteristic of croup. Other features can include:

- Fever

- Sore throat

- Restless and irritable

- Muffled or hoarse voice

- ‘Tripod’ positioning: leaning forward, hyperextended neck, chin forward (an attempt to maximise airflow)

- Stridor

Diagnosis & investigations

Acute epiglottitis requires rapid assessment and clinical diagnosis to prevent further airway compromise.

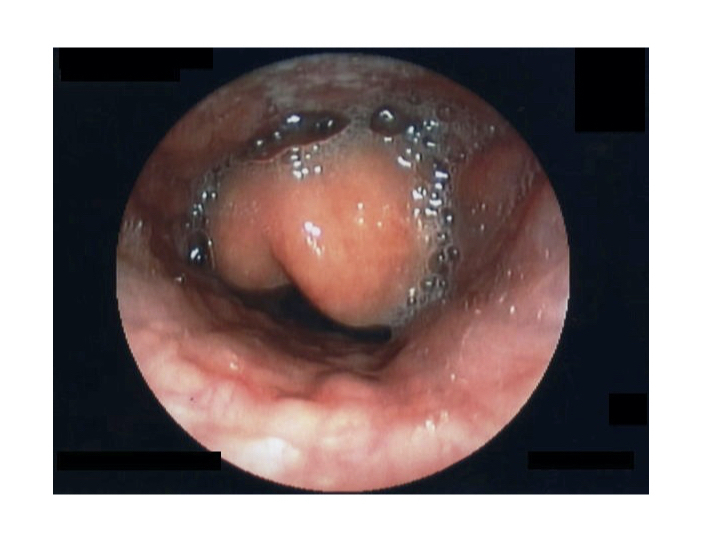

There should be a low threshold for the suspicion of acute epiglottitis due to the risk of rapid deterioration. Diagnosis is based on visualisation of the inflamed epiglottis, however, this should only be attempted by a clinician who is trained to deal with the airway.

Inflamed epiglottis, suggestive of acute epiglottitis

Image courtesy of CC BY-SA 3.0

There is concern that attempts to visualise the back of the throat by an untrained clinician could lead to cardiorespiratory arrest by a variety of mechanisms (e.g. functional obstruction, laryngospasm). Therefore, if a child has classical signs of epiglottitis prompt involvement of a clinician with paediatric airway skills is needed before visualisation. This is so the airway can be secured if deterioration during, or after, visualisation occurs.

Other investigations

The initial priority is airway management. Subsequent investigations may include blood tests, blood cultures, epiglottic cultures (only if airway secure), or imaging. Imaging may have a role (e.g. MRI/CT for suspected abscess). Lateral radiographs of the neck can be used to look for oedema of the epiglottis (the classic 'thumb sign'), but direct visualisation is the standard of care.

Management

The priority of acute epiglottitis treatment is airway management by an experienced clinician trained in paediatric airways.

All patients require review from senior members of the anaesthetic and ENT teams. The key aspects of treatment include airway management and antibiotics.

- Airway management: clinician with paediatric airway skills. Maintain oxygenation. Intubation if respiratory arrest or compromise. Do NOT use supraglottic airways.

- Antibiotics: refer to local guidelines. Intravenous (IV) broad-spectrum antibiotics should be commenced in all patients.

- Other treatments: IV steroids and adrenaline nebulisers are often given. IV fluids should be given as appropriate.

- Other measures: try to prevent agitation of the child. Referral to the paediatric intensive care unit. Monitor for complications (e.g. abscess), if intubated will need reassessment of epiglottis prior to extubation

Vaccination

All children should have the Hib vaccination as part of the usual childhood vaccination programme. This has dramatically decreased the incidence of acute epiglottitis.

Complications

Prognosis is good when the diagnosis and treatment of acute epiglottitis are instigated promptly.

Complications may include abscess formation, sepsis, respiratory arrest and death. Early recognition and treatment can prevent the need for intubation and development of complications.

Last updated: March 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback