Keratitis

Notes

Overview

Keratitis is a broad clinical term that refers to inflammation of the cornea.

The cornea is the transparent dome-shaped structure at the front of the eye that is continuous with the sclera. Keratitis refers to inflammation of the cornea, which is commonly secondary to an infectious cause (e.g. viral, bacterial, fungal). Keratitis is characterised by pain, redness, irritation, photophobia, and in more severe cases, reduced visual acuity. Without prompt treatment, patients can develop corneal ulcers, and with certain aetiologies such as bacterial keratitis, sight can be threatened.

Infectious keratitis is often used interchangeably with the term corneal ulcer as the two commonly present together. A corneal ulcer refers to a defect within the epithelium of the cornea that involves the stroma. The term ‘ulcerative keratitis’ may also be used to describe the presence of corneal inflammation and ulceration.

Non-ulcerative keratitis

Image courtesy of Eddie314 (Wikimedia commons)

Corneal anatomy

The cornea is composed of five distinct layers and is important for focusing light onto the retina.

The cornea forms the clear anterior surface of the eye and is continuous with the sclera. The two parts meet at a point termed the limbus which can be seen as the intersection between the white sclera and the coloured iris.

The cornea is a collagen-based structure that helps focus light onto the retina. It is composed of five distinct layers:

- Epithelium: outermost layer of the cornea that helps maintain its smoothness. It acts as a protective barrier against foreign particles and microorganisms.

- Bowman's layer: thin acellular layer that provides structural support.

- Stroma: accounts for approximately 90% of the total corneal thickness. Composed of highly organised collagen fibres that enable both strength and transparency.

- Descemet's membrane: thin cell-free layer that acts as a protective barrier. Composed mainly of type IV collagen.

- Endothelium: innermost layer of the cornea, which consists of a single layer of cells. Regulates fluid levels within the cornea.

Epidemiology

In the UK, keratitis is commonly secondary to a bacterial infection.

The epidemiology of keratitis varies around the world. This is due to the change in climate and responsible pathogens. The rates of microbial (i.e. infectious) keratitis have been increasing with the rising use of contact lenses. The true incidence of microbial keratitis varies but rates have been reported between 3.3-52.1 per 100,000.

Aetiology & pathophysiology

The cause of keratitis may be infectious or non-infectious.

Keratitis occurs when there is inflammation of the cornea. The cause of keratitis is broadly divided into infectious and non-infectious:

- Infectious keratitis: bacterial, viral, fungal, protozoal

- Non-infectious keratitis: autoimmune, exposure, vitamin A deficiency

Keratitis is commonly secondary to an infective microorganism. Any disruption to the normally protective host defence mechanisms of the external eye can lead to established infection. This may include physical irritation, reduced tear production, and inadequate eye closure, amongst others. The associated inflammatory response can lead to polymorphonuclear cells infiltrating the corneal stroma and causing destruction of Bowman’s membrane. In severe cases, there can be significant tissue destruction and breaching of Descemet’s membrane. The main consequence of severe keratitis is blindness.

Risk factors

Anything that damages the integrity of the corneal epithelium can increase the risk of keratitis. Important risk factors include:

- Contact lens use

- Trauma

- Immunosuppression

- Dry eyes

- Corticosteroid eye drops

- UV light exposure

- Swimming in contaminated waters

Infectious keratitis

Bacterial keratitis is a serious condition that can cause loss of vision without prompt treatment.

A variety of infective pathogens can lead to keratitis. Bacterial keratitis can be particularly destructive, and prompt ophthalmic assessment is pertinent to prevent sight loss and minimise scarring.

Viral

Two common causes of viral keratitis include adenovirus and herpes simplex virus (HSV).

Adenovirus commonly causes conjunctivitis but certain strains can affect the cornea. This is usually characterised by features of viral conjunctivitis (red eye, watery eye, irritation) for a few days that are followed by typical corneal symptoms including pain, foreign body sensation, and photophobia. Collectively, it is termed keratoconjunctivitis.

HSV is a major cause of blindness worldwide. It is predominantly caused by the HSV-1 subtype following viral reactivation (the virus remains dormant in nerve ganglia after initial infection). Only 5% of cases are due to primary infection. The classification of HSV keratitis and its pathophysiology is complex. However, the most common form is epithelial keratitis (i.e. affecting the corneal epithelium) which can be categorised into different subtypes.

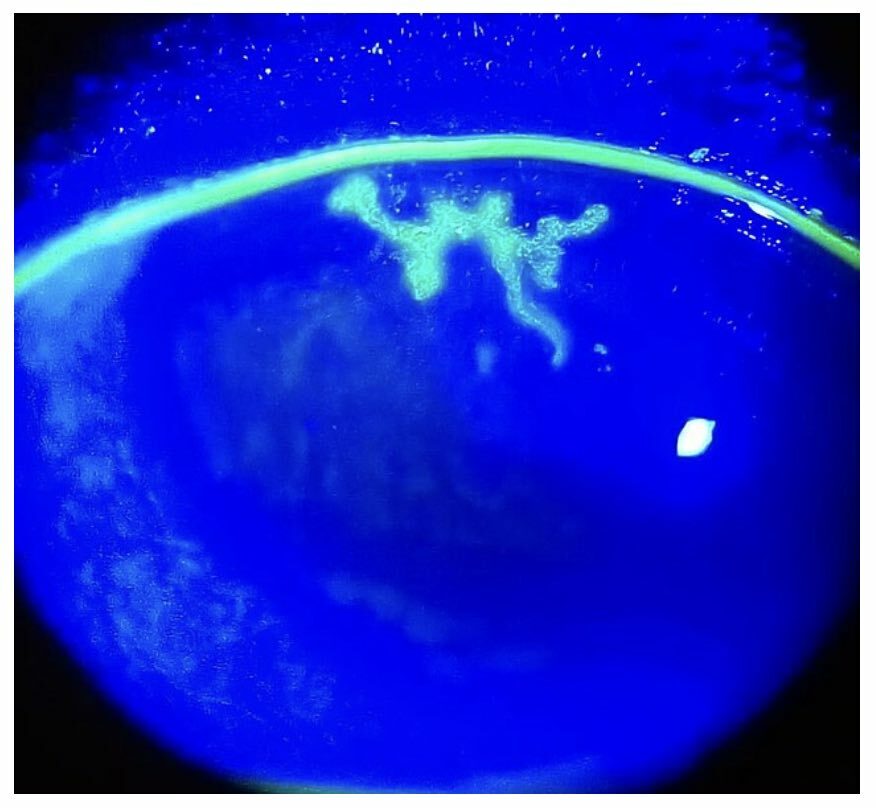

Dendritic keratitis is a subtype of epithelial HSV keratitis that is characterised by the presence of dendritic lesions. These are initial punctate lesions that can coalesce to form dendritiform (i.e. branching tree-like) patterns and lead to ulcers.

Dendritic ulcer under fluorescein staining

Image courtesy of Imrankabirhossain (Wikimedia Commons)

Bacterial

A variety of bacterial pathogens may lead to Keratitis including:

- Staphylococcus aureus

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus

- Streptococcus pneumoniae

- Moraxella catarrhalis

These are the most common causes and typically rely on a compromised epithelium to initiate infection. Improper use of contact lenses is the most likely predisposing factor. Other organisms may penetrate the epithelium directly due to high virulence including Corynebacterium diphtheriae and Neisseria species.

Fungal

Fungi are ubiquitous in the environment but the development of fungal keratitis is rare. It is more common in tropical regions and there is usually an underlying predisposing factor such as immunosuppression, eye trauma, or contact lens use. Common causative fungi include;

- Aspergillus spp.

- Fusarium spp.

- Candida spp.

Acanthamoeba

Acanthamoeba refers to the genera of a group of protozoa (single-celled eukaryotes) that can cause human disease. They are ubiquitous in the environment and may lead to keratitis in the developed world due to improper contact lens use. A common route of infection is the use of non-sterile tap water in preparation of lens solution. It typically affects a single eye and can lead to chronic infection and visual loss.

Non-infectious keratitis

Non-infectious causes may be local due to corneal irritation or systemic conditions.

Non-infectious causes of keratitis can occur due to local corneal inflammation from trichiasis (inward-growing eyelash), chronic blepharitis secondary to S. Aureus antigens, or a foreign body. Alternatively, it may be due to a systemic condition, which can include:

- Connective tissue disease (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis)

- Vasculitis (e.g. granulomatosis with polyangiitis)

- Vitamin A deficiency

- Severe allergic response (e.g. vernal keratoconjunctivitis)

- Photokeratitis (e.g. intense UV light exposure)

- Neurotrophic keratitis (absence or reduce corneal sensitivity)

Autoimmune causes of keratitis (e.g. connective tissue disease, vasculitis) collectively cause peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK).

Clinical features

Keratitis is characterised by eye redness, pain, blurry vision, and photophobia.

Keratitis is one of the major differentials for a painful red eye. The presence of overt pain, photophobia, and reduced visual acuity are key signs there is involvement of the cornea.

Symptoms

- Eye redness

- Eye pain

- Blurred vision

- Photophobia (sensitivity to light)

- Increased lacrimation (excess tear production)

- Difficulty opening the eye

- Foreign body sensation

- Eye discharge

- Associated conjunctivitis

Signs

The signs of keratitis may be profound with evidence of corneal ulceration, oedema, and profound redness. Corneal infiltrates may be present that refer to collections of inflammatory cells that appear as grey spots under magnification. There may be mucopurulent discharge and patients may have a hypopyon (i.e. accumulation of immune cells within the anterior chamber).

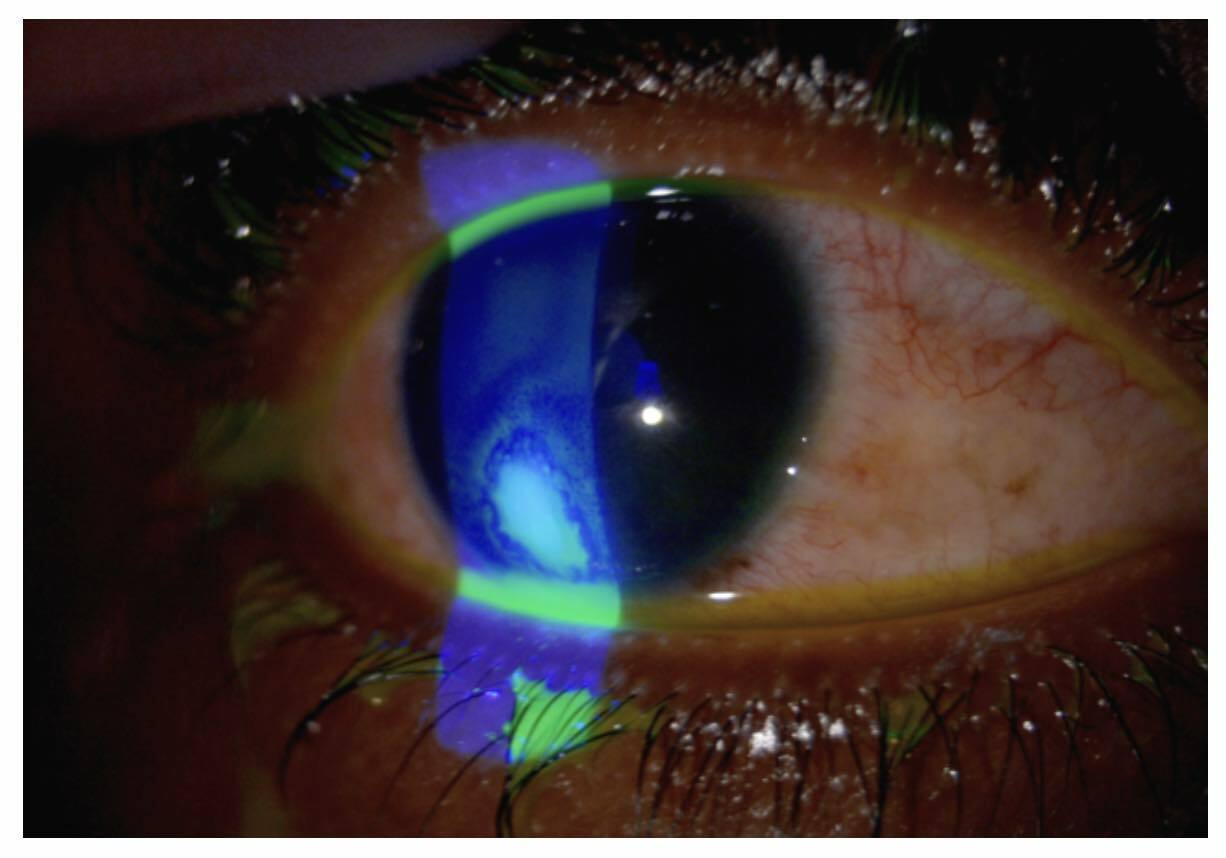

Corneal ulcer

A corneal ulcer refers to a defect in the epithelium that involves the stroma. It should be considered an ophthalmic emergency because it can be sight-threatening if untreated. It is essential to include an infective cause and the defect can be better visualised with fluorescein staining.

Corneal ulcer under fluorescein staining

Image courtesy of Yoanmb (Wikimedia Commons)

Corneal abrasion

A corneal abrasion only involves the epithelium of the cornea and occurs secondary to trauma or contact lens use. However, a corneal abrasion can present with similar features of eye redness, pain, photophobia, and foreign body sensation. Therefore, it is critical to exclude a more serious cause (e.g. infective keratitis). Patients with evidence of infiltrates, white spots, or early ulcerative should be referred for urgent ophthalmic assessment.

Diagnosis & work-up

The diagnosis of infective keratitis is usually clinical whilst awaiting confirmatory laboratory investigations.

Keratitis is initially a clinical diagnosis due to the potential for serious complications if left untreated. This enables prompt initiation of treatment whilst further investigations are conducted to determine the exact cause and possible differential diagnoses.

A formal eye examination is essential to determine the diagnosis, associated complications, and need for urgent ophthalmic assessment. A formal slit-lamp examination should be completed. The eye examination should include;

- Penlight examination: should be completed to exclude penetrating trauma and assess the pupillary reaction. Also useful to exclude a foreign body.

- Eyelid eversion: this is to assess for any retained foreign body (commonly lodged onto the pretarsal sulcus of the upper lid).

- Visual acuity testing: A Snellen chart is most commonly used.

- Eye movements: assessment of extra-ocular muscle function.

- Fundoscopy: may be very difficult to complete in the presence of an acutely painful eye and small pupils.

- Fluorescein examination: This involves the application of fluorescein drops that stain the basement membrane. Should only be completed once other eye assessments have been completed and penetrating trauma excluded. Ulcer and abrasions will appear yellow to the naked eye and additional light filters (e.g. cobalt blue) can be used to enhance visualisation.

NOTE: specific patterns on fluorescein staining can aid with the suspected diagnosis (e.g. typical dendritic lesion of HSV keratitis).

Local anaesthetic drops

The eye examination is best completed without topical analgesia as they have been shown to affect corneal healing in animal studies. However, if the patient is unable to tolerate the examination, once penetrating trauma has been excluded, a small application of a local anaethestic (e.g. lidocaine or proparacaine 0.5) can be used.

Further investigations

Additional investigations can be completed to help determine the underlying aetiology, which include:

- Corneal scrapings: used to send off for gram staining (e.g. bacterial, acanthamoeba) formal culture (e.g. bacterial), and PCR (e.g. HSV).

- Corneal biopsy: considered in patients who do not respond to treatment.

Management

Patients with suspected keratitis or corneal ulceration require same-day ophthalmic assessment.

The specific management of keratitis depends on the underlying cause.

Referral

Infectious keratitis is a potentially sight-threatening diagnosis and presents with many ‘red flag’ features including photophobia, corneal defect(s), moderate-to-severe eye pain, and/or reduced visual acuity. Therefore, patients should be referred for urgent same-day ophthalmic assessment.

Bacterial

Bacterial keratitis is treated with topical antibiotics. Severe infections and specific pathogens may require the addition of systemic antibiotic therapy to the treatment regimen. A typical choice is the use of topical Ciprofloxacin every 2-6 hours. Other agents may be added to this depending on local guidelines and suspected organisms.

Due to antibiotic resistance, cultures are strongly recommended to guide treatment (e.g. corneal scrapings).

Viral

The choice of treatment depends on the suspected viral pathogen. Epithelial HSV keratitis is treated with topical aciclovir. For more invasive disease involving the stroma, oral aciclovir may be added to the regimen, and under the special guidance of an ophthalmologist, this may be combined with topical corticosteroids.

In patients with adenovirus keratitis, treatment is usually supportive and personal hygiene is very important.

Acanthamoeba

Patients with Acanthamoeba keratitis should be treated with a combination of topical polyhexamethylene biguanide and chlorhexidine that may be combined with pentamidine. Other treatments may be indicated in those with a poor response and chronic refractory cases may require surgery (e.g. corneal transplant).

Fungal

Fungal keratitis is very difficult to treat and depends on the underlying fungal pathogen. A variety of treatment options can be used including topical (e.g. natamycin) and systemic (e.g. Voriconazole) antifungals. In chronic or resistant cases ophthalmic surgery may be required.

Non-infective

The management of non-infective causes is complex and depends on the underlying cause. Any local irritating factor should be addressed (e.g. removal of lashes in trichiasis) and systemic autoimmune conditions often require immunosuppression and the use of topical steroids under the guidance of an ophthalmologist.

Complications

The most severe complications of keratitis is blindness without correct diagnosis and prompt treatment.

Major complications associated with keratitis include:

- Corneal scarring

- Visual loss

- Descemetocele (herniation of Descemet's membrane through corneal stromal defect)

- Endophthalmitis (inflammation/infection of internal eye structures)

- Secondary glaucoma (increased intra-ocular pressure due to inflammatory process and abnormal drainage)

- Corneal melting and perforation

NOTE: inflammation of the cornea can lead to the formation of ulcers. As the inflammatory progress continues there is progressive destruction and thinning of the cornea known as ‘melting’, which is a prelude to corneal perforation.

Last updated: July 2023

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback