Pre-eclampsia

Notes

Introduction

Pre-eclampsia is a complication of pregnancy characterised by hypertension and proteinuria with or without oedema.

It is a systemic disease whose exact aetiology is still not fully understood, though uteroplacental dysfunction and widespread maternal endothelial dysfunction is seen. It is a significant cause of maternal morbidity and mortality.

Severe cases may result in seizures (eclampsia), multi-organ failure (in particular the liver and kidneys) and significant coagulopathy.

There are a number of terms to be aware of which may be variably defined. Here we present the definitions from the International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy (ISSHP), The classification, diagnosis and management of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: A revised statement from the ISSHP, 2014.

- Chronic hypertension: pre-existing hypertension.

- Gestational hypertension: new-onset hypertension (≥ 140 systolic, ≥ 90 diastolic) after 20 weeks gestation.

- Pre-eclampsia: new-onset hypertension (≥ 140 systolic, ≥ 90 diastolic) - or superimposed on chronic hypertension - after 20 weeks gestation and proteinuria, uteroplacental dysfunction or other maternal organ damage. It should be noted that pre-eclampsia may occur up to 4-6 weeks after giving birth.

- Whitecoat hypertension: hypertension confirmed only to occur due to the healthcare professional presence/environment. Ambulatory monitoring may be used.

It can be challenging to make a diagnosis of pre-eclampsia in the setting of pre-existing hypertension or gestational hypertension. Pre-existing renal disease from proteinuria may also add layers of complexity. These patients need close specialist monitoring to identify any signs of pre-eclampsia.

Epidemiology

According to the Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, pre-eclampsia affects 1-5 in 100 pregnant women.

These figures vary depending on parity. The risk of pre-eclampsia is highest in the first pregnancy (4%), which decreases in the second and third pregnancies. However, among people who have pre-eclampsia the risk in subsequent pregnancies significantly increases.

If a pregnancy is affected by pre-eclampsia then the risk of the subsequent pregnancy being affected also depends on the gestational age of the original birth, for example:

- Born 28-34 weeks: 1 in 3 affected by pre-eclampsia in subsequent pregnancy

- Born 34-37 weeks: 1 in 4 affected by pre-eclampsia in subsequent pregnancy

- Born ≥37 weeks: 1 in 6 affected by pre-eclampsia in subsequent pregnancy

The MBBRACE-UK is a national audit that reviews the causes of maternal deaths. Their figures show four deaths per 100,000 pregnancies between 2016-2018 from pre-eclampsia and eclampsia, numbers that reflect a significant fall over the past 50 years.

The exact aetiology and contributing factors can be difficult to assess and attribute, for example in the 2015-17 report they note that of nine women who died of aortic dissection, five were hypertensive and two had pre-eclampsia.

Risk stratification

NICE risk stratify certain women as high risk to help guide preventative management.

NICE NG 133: Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management (2019), describe high risk and moderate risk factors that can be used to guide preventative therapy (see chapter below). Women are considered high risk if they have one of the following high-risk factors:

- History of hypertensive disease during a previous pregnancy

- Chronic kidney disease

- Autoimmune disease (e.g. systemic lupus erythematosus or antiphospholipid syndrome)

- Type 1 or type 2 diabetes

- Chronic hypertension

Women are considered high risk if they have two of the following moderate risk factors:

- First pregnancy

- Aged 40 years or older

- Pregnancy interval of more than 10 years

- BMI of 35 kg/m2 or greater at the first visit

- Family history of pre-eclampsia

- Multiple pregnancy

Studies have also indicated higher incidence in those with African and Caribbean heritage.

Prevention

Women with one high risk or two moderate risk factors should be offered aspirin prophylaxis.

NICE advise the use of Aspirin 75mg-150mg once daily from 12 weeks until birth in at-risk women to reduce the chance of developing pre-eclampsia.

Standard lifestyle and exercise advice for pregnancy should be given. Ensure modifiable risk factors are addressed and diabetes managed as per guidance.

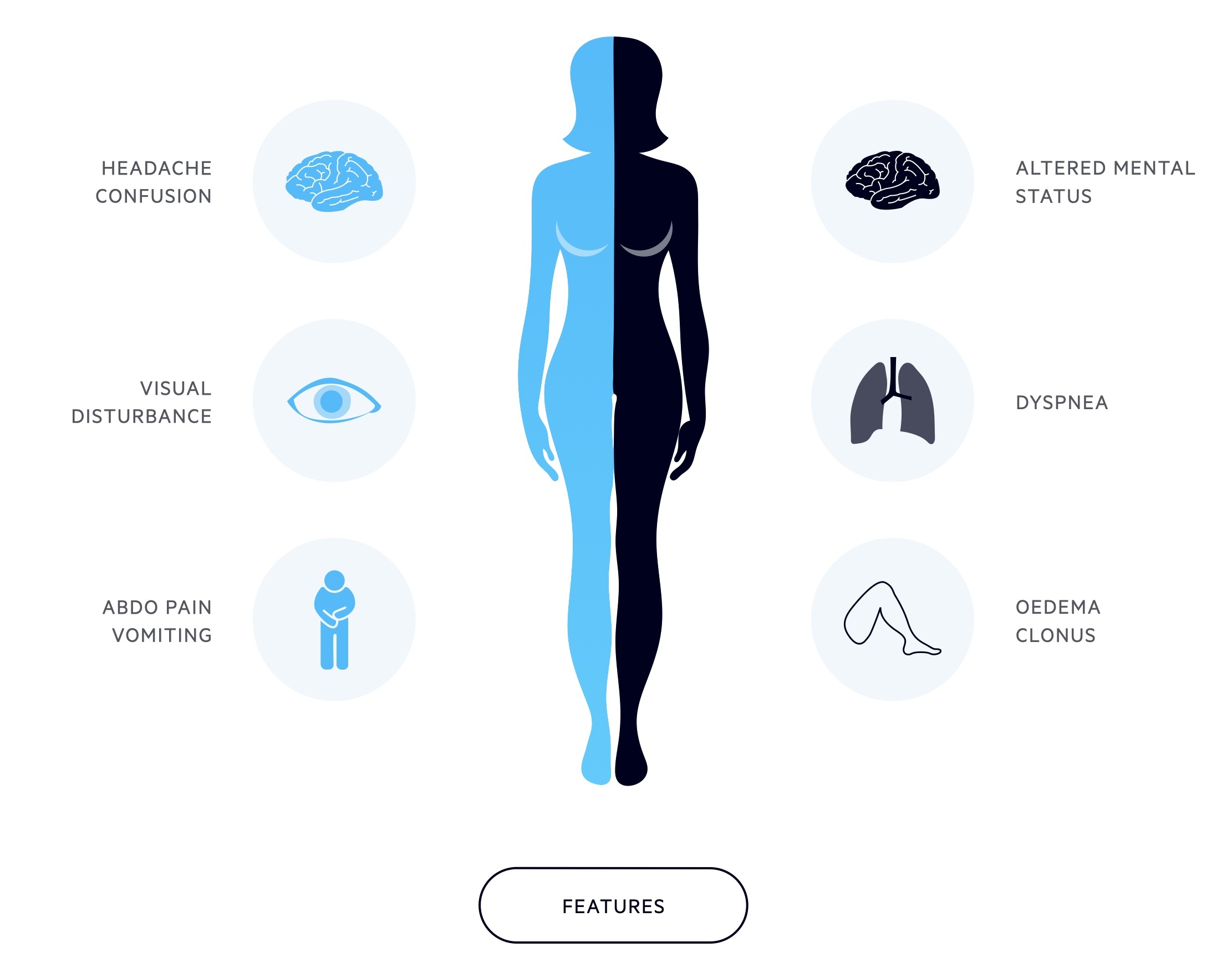

Clinical features

Pregnant women should be advised to present urgently to hospital if they develop features consistent with pre-eclampsia.

Pre-eclampsia is frequently asymptomatic, picked up during routine antenatal screening based on raised blood pressure and protein in the urine. In more severe disease symptoms may develop including headaches, visual disturbances and abdominal pain.

Onset is after 34 weeks in around 85% of patients. The development of pre-eclampsia before 34 weeks is considered 'early onset'. Pre-eclampsia occurring before 20 weeks is rare and may be associated with a molar pregnancy or antiphospholipid syndrome.

Symptoms

- Headache

- Visual disturbance

- Oedema (facial, peripheral)

- Abdominal pain (typically upper abdominal/epigastric)

- Vomiting

Signs

- Altered mental status

- Dyspnea

- Clonus

- Oedema

Investigations

The diagnosis of pre-eclampsia is made by the combination of hypertension (after 20 weeks) and proteinuria.

Bedside

- Blood pressure

- Vital signs

- Urine dipstick and culture

- Albumin:creatinine ratio or protein:creatinine ratio

- 24-hour urinary collection (not routinely sent)

NOTE: Do not use first morning void to quantify proteinuria.

Blood tests

- FBC: falling platelet counts may herald the development of HELLP syndrome.

- Renal function: serum creatinine should be monitored for signs of developing acute kidney injury.

- LFT: derangement of transaminases is common, also become elevated in HELLP syndrome.

- Clotting screen: in severe cases, coagulopathy may develop.

Imaging

- USS: allows assessment of foetal development.

- CT/MRI: cerebral imaging may be considered if concern exists of an acute intracranial event (e.g. acute haemorrhage).

Special

Placenta growth factor-based tests may be used between 20 and 34+6 weeks gestation, particularly in patients with pre-existing chronic hypertension or gestational hypertension, to help rule in or rule out pre-eclampsia.

Management

The care of any women with pre-eclampsia should be lead by a senior obstetrician.

Optimal management of patients with pre-eclampsia may demand input from multiple teams apart from the obstetricians and can include haematology, intensive care/anaesthetics and neonatology.

The only ‘cure’ is delivery though if patients are stable and closely monitored this can be delayed until 37 weeks. NICE guideline 133 gives an overview of the management of pre-eclampsia.

Conservative, hypertension (140/90 - 159/109)

- Place of care: admit if any clinical concerns for mother or baby, or if scores high risk on fullPIERS or PREP-S. In practice, most patients will be admitted for a period of observation.

- Anti-hypertensives: if BP remains ≥ 140/90 offer antihypertensives. Labetalol is often offered first line, nifedipine may be used as an alternative if labetalol is not appropriate. Methyldopa may be offered if neither is appropriate.

- BP monitoring: target BP < 135/85. BP should be measure at least every 48hrs and at a greater frequency if an inpatient.

- Blood tests: repeat FBC, UE, LFT at least twice a week.

- Foetal assessment: carry out USS and CTG at diagnosis. Repeat USS at 2 weekly intervals, auscultate foetal heart at every visit.

Conservative, severe hypertension (≥ 160/110)

- Place of care: admit to hospital. Consider discharge if falls below this under senior guidance.

- Anti-hypertensives: offer antihypertensives to all women. Labetalol is often offered first line with nifedipine if labetalol is not appropriate. Methyldopa may be offered if neither are appropriate.

- BP monitoring: target BP < 135/85. Monitor BP every 15-30 mins until <160/110 and then at least four times a day whilst an inpatient.

- Blood tests: repeat FBC, UE, LFT at least three times a week.

- Foetal assessment: carry out USS and CTG at diagnosis. Repeat USS at 2 weekly intervals, auscultate foetal heart at every visit.

Timing of birth

Where possible, in the absence of severe pre-eclampsia, patients should be managed conservatively until 37 weeks. NICE guideline 133 recommend early birth (i.e. < 37 weeks) should be considered in the following instances (not an exhaustive list):

- Inability to control maternal blood pressure despite using 3 or more classes of antihypertensives in appropriate doses

- Maternal pulse oximetry less than 90%

- Progressive deterioration in liver function, renal function, haemolysis, or platelet count

- Ongoing neurological features, such as severe intractable headache, repeated visual scotomata, or eclampsia

- Placental abruption

- Reversed end-diastolic flow in the umbilical artery doppler velocimetry, a non-reassuring cardiotocograph, or stillbirth.

The thresholds for early birth should be discussed with the mother and decisions about timings advised by consultant obstetricians.

- Before 34 weeks: in absence of contraindications (see above) continue surveillance. If early birth required consider magnesium sulphate (neuroprotection) and corticosteroids.

- 34 to 36 weeks: in absence of contraindications (see above) continue surveillance. If early birth required consider corticosteroids.

- 37 weeks onwards: initiate birth within 24-48 hours

Severe pre-eclampsia

- Blood pressure: control is key and may require multiple agents such as labetalol, nifedipine and hydralazine.

- Fluid balance: close monitoring of fluid balance is required. There is a risk of both renal impairment and pulmonary oedema.

- Complications: a number of life-threatening complications may develop including HELLP syndrome, disseminated intravascular coagulation and adult respiratory distress syndrome.

- Delivery: the decision should be lead by a consultant obstetrician and when possible taken in conjunction with the mother. A holistic view is required and must come from the most experienced decision-makers.

Eclampsia

Seizures represent the onset of eclampsia. This is an obstetric emergency requiring an immediate response, commencement of oxygen and securing of the airway. The mother should be placed in the left lateral position. Magnesium sulphate is the first-line treatment for eclamptic seizures. Intubation may be required and cerebral imaging considered. Delivery is the definitive management.

Complications

Numerous complications can occur during pre-eclampsia including HELLP syndrome and DIC.

- HELLP Syndrome: Haemolysis Elevated Liver enzymes Low Platelets syndrome is a severe complication of pregnancy that normally occurs in patients suffering with pre-eclampsia. The details of this condition are beyond the scope of this note.

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation: Life-threatening coagulopathy where wide-spread activation of the clotting system leads to micro-thrombi formation and consumption of clotting factors. It can lead to haemorrhage and multi-organ failure.

Last updated: March 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback