Hypocalcaemia

Notes

Overview

Hypocalcaemia is defined as a serum corrected calcium concentration < 2.2 mmol/L.

Hypocalcaemia can lead to dangerous cardiac arrhythmias and requires urgent identification and treatment. The normal serum calcium concentration is 2.2-2.6 mmol/L and this should be corrected for albumin.

Hypocalcaemia is a common electrolyte abnormality with a wide range of causes. It is commonly seen in chronic kidney disease (CKD) and vitamin D deficiency. Acute symptomatic hypocalcaemia is most often seen following thyroidectomy (removal of the thyroid gland) which can disrupt the parathyroid glands that are needed for in parathyroid hormone (PTH) secretion.

Acute hypocalcaemia can be further divided as follows:

- Mild - corrected calcium ≥ 1.9 mmol/L

- Severe - corrected calcium < 1.9 mmol/L

Calcium physiology

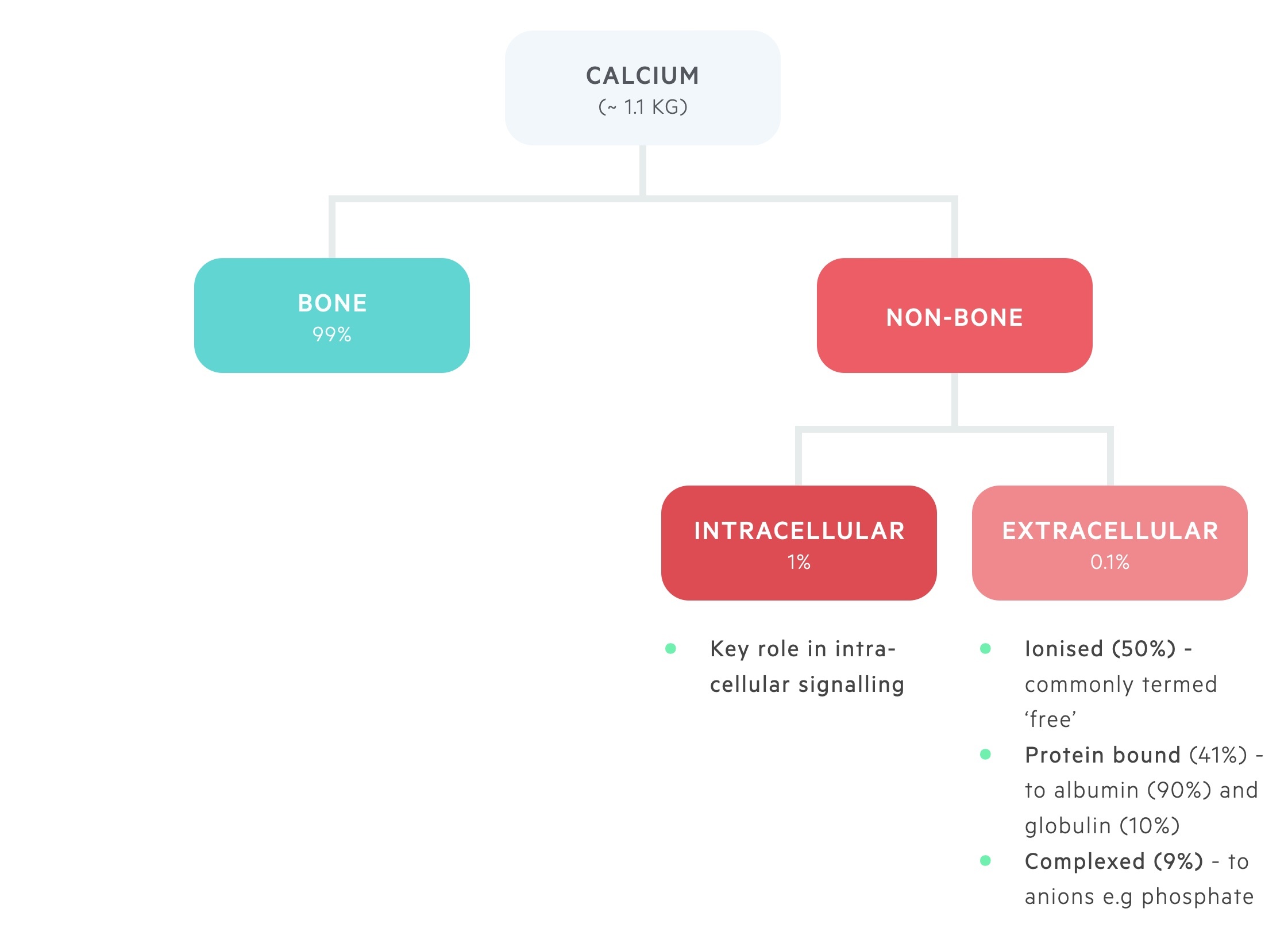

Calcium is distributed between bone and the intra- and extra-cellular compartments.

The majority of body calcium, 99%, is stored in bone.

Approximately 1% of total body calcium is found within the intracellular compartment. Here it plays a key role in intracellular signalling.

Around 0.1% of total body calcium is found within the extracellular pool, this is divided into:

- Ionised (~ 50%) - metabolically active, or ‘ionised’, free pool of calcium.

- Bound (~ 41%) - bound to albumin (90%) and globulin (10%).

- Complexed (~ 9%) - forms complexes with phosphate and citrate.

The balance between stored calcium and the extracellular pool of calcium is a closely regulated process. It is controlled by the interaction of three hormones; parathyroid hormone (PTH), vitamin D and calcitonin.

Decreased extracellular calcium is detected by the calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) on the parathyroid gland. The parathyroid glands respond to the fall in serum calcium by releasing PTH. PTH stimulates the resorption of calcium from bone, activation of vitamin D (leads to calcium absorption from enterocytes) and increased renal tubular reabsorption of calcium.

Conversely, a rise in extracellular calcium detected by the CaSR has the opposite effect. It leads to a reduction in the release of PTH and stimulates the release of calcitonin. This combined effect helps decrease bone resorption and promotes calcium excretion in the kidneys.

Corrected calcium

Serum calcium levels may be 'corrected' by adjusting them for the albumin level.

As described in the chapter above around 40-45% of extracellular calcium is bound to albumin and around 50% physiologically active and ‘free’ or ionised. Due to calcium binding to albumin, a corrected calcium level is determined by taking into account the albumin level. With modern laboratories, a corrected calcium result is normally automated.

It is estimated that the serum calcium concentration falls by 0.25 mmol/L (0.8 mg/dL) for every 10 g/L (1 g/L) fall in serum albumin concentration. This can be calculated manually using the following formula:

Corrected calcium (mg/dL) = serum calcium (mg/dL) + 0.8 x (4.0 - serum albumin [g/dL])

Aetiology

Major causes of hypocalcaemia can be determined in relation to the parathyroid hormone concentration.

There are multiple causes of hypocalcaemia that are broadly be divided into four groups:

- Hypocalcaemia with raised PTH (discussed below)

- Hypocalcaemia with low PTH (discussed below)

- Hypocalcaemia related to magnesium metabolism

- Medication-induced hypocalcaemia

Magnesium metabolism

Hypomagnesaemia is a common cause of hypocalcaemia because it impairs the action of PTH leading to resistance. This predominantly occurs at markedly low magnesium levels (< 0.4 mmol/L). In more severe hypomagnesaemia it can cause a reduction in PTH secretion. Therefore, when assessing a patient with hypocalcaemia it is important to check and replace magnesium. If severe hypomagnesaemia is present, calcium will not improve without normalisation of magnesium.

Rarely, hypermagnesaemia (markedly raised levels e.g. > 2.5 mmol/L) can cause hypocalcaemia through suppression of PTH secretion.

Medication-induced hypocalcaemia

Several medications can cause hypocalcaemia by various mechanisms:

- Bisphosphonates (bind calcium in bone and inhibit osteoclasts)

- Calcium chelators (e.g. citrate used to inhibit coagulation in banked blood)

- Denosumab (monoclonal antibody to RANK ligand)

- Cinacalcet (calcimimetic that mimics the action of calcium on calcium-sensing receptors)

Hypocalcaemia & raised PTH

In these causes, PTH is secreted in response to low calcium in an attempt to restore normal calcium levels.

Vitamin D deficiency

This is a very common cause of hypocalcaemia. Linked to poor diet and absence of ultraviolet light.

Chronic kidney disease

CKD is a major cause of hypocalcaemia as part of a wider calcium-phosphate handling disorder known as ‘CKD mineral and bone disorders’.

This can cause hypocalcaemia through:

- Reduced activation of vitamin D

- Reduced renal absorption of calcium

- Reduced renal excretion of phosphate

CKD can lead to a marked rise in PTH in response to hypocalcaemia known as secondary hyperparathyroidism.

Pseudohypoparathyroidism

When peripheral tissue is unresponsive to the effects of PTH due to an alteration in the PTH receptor, the condition is known as pseudohypoparathyroidism. The condition presents in childhood with characteristic features.

The reason for the term 'pseudo' is because the biochemical picture is similar to a lack of PTH (hypoparathyroidism) with hypocalcaemia and hyperphosphataemia. However as it is due to resistance to PTH rather than reduced secretion the PTH is elevated.

Extravascular deposition

Many conditions lead to the sequestration of calcium. This causes hypocalcaemia and an appropriate rise in PTH in an attempt to normalise the serum calcium concentration.

Causes include:

- Tumour lysis syndrome: release of intracellular phosphate which binds to plasma calcium

- Rhabdomyolysis: similar mechanism to tumour lysis syndrome

- Acute pancreatitis: free fatty acids released in the inflammation are thought to bind and cause precipitation of calcium

- Osteoblastic metastases: deposition of calcium around metastatic sites. Usually seen in breast and prostate cancer.

Other

- Severe illness: hypocalcaemia thought to be due to low magnesium levels and PTH resistance

- Blood transfusions: citrate in banked blood to prevent coagulation can bind to calcium and cause hypocalcaemia.

Hypocalcaemia & low PTH

Hypocalcaemia secondary to low PTH is classically seen following thyroid surgery.

Surgery

Hypocalcaemia with a low PTH is most commonly related to surgery, which can occur following any neck surgery (e.g. thyroid, parathyroid, dissection for cancer). Post-surgical hypocalcaemia can be divided into three types:

- Transient: usually from disruption of blood supply or removal of 1-2 glands. May last days, weeks or months. Seen in 20% after surgery for thyroid cancer

- Intermittent: recurrent episode of hypoparathyroidism and subsequent hypocalcaemia due to poor PTH reserve

- Permanent: requires life-long treatment. Affects up to 3% undergoing surgery for thyroid cancer.

Hypoparathyroidism

This is most commonly an autoimmune disorder that results in immune-mediated destruction of the parathyroid glands. Also occurs due to autoantibodies that bind to the calcium-sensing receptors (CaSR), which decreases PTH secretion.

Other

Rarely hypocalcaemia can be due to damage to the parathyroid glands by infiltration or radiation. Additionally, abnormal parathyroid gland development, as seen in DiGeorge syndrome, can result in hypocalcaemia.

Pathophysiology

Untreated, hypocalcaemia can cause dangerous cardiac arrhythmias and seizures.

Calcium is essential for many functions and structures in the body. This includes stability of membrane potential, neural transmission, bony structures, coagulation and intracellular signalling.

Hypocalcaemia can lead to neuromuscular irritability and tetany. In severe hypocalcaemia life-threatening arrhythmias and seizures can develop.

Clinical features

Acute hypocalcaemia is characterised by paraesthesia and muscle spasms.

Symptoms

This usually occurs at calcium concentrations < 1.9 mmol/L

- Paraesthesia (numbness and tingling sensation, usually located peri-orally and in the fingers/toes)

- Muscle cramps

- Wheezing

- Voice changes (laryngospasm)

- CNS disturbance (seizures, irritability, confusion)

- Chest pain (angina)

- Palpitations (arrhythmias)

Signs

Two classical eponymous signs are associated with hypocalcaemia:

- Trousseau's sign: development of carpopedal spasm* following inflation of a blood pressure (BP) cuff above systolic BP

- Chvostek's sign: tapping over the course of the facial nerve in the pre-auricular area causes muscle spasms (seen as twitching of the face, mouth or nose)

* Carpopedal spasm refers to flexion at the wrist and metacarpophalangeal joints, extension of the interphalangeal joints and adduction of the thumb

Diagnosis & investigations

The diagnosis of hypocalcaemia is based on a serum corrected calcium < 2.2 mmol/L.

It is important to distinguish whether the cause of hypocalcaemia is acute or chronic. Acute severe hypocalcaemia (< 1.9 mmol) is a medical emergency that requires urgent treatment and cardiac monitoring.

Usual investigations to determine the underlying cause include:

- Bone profile

- Urea & electrolytes

- Vitamin D

- Parathyroid hormone

- Magnesium

- ECG (low calcium can cause a prolonged QT interval and arrhythmias)

Other investigations are guided by the clinical presentation. For example, a lipase or amylase in suspected acute pancreatitis or a uric acid level if tumour lysis syndrome is suspected.

Management

Acute severe hypocalcaemia (< 1.9 mmol/L) is a medical emergency.

Acute hypocalcaemia

The management of acute hypocalcaemia depends on whether it is mild or severe. Please note, most centres performing thyroid or parathyroid surgery will have set local protocols for the monitoring and management of hypocalcaemia around the time of surgery.

Mild hypocalcaemia (≥ 1.9 mmol/L)

- Oral calcium supplements (e.g. Sandocal 2 tablets BD or Adcal D3 1-3 tablets BD)

- Vitamin D replacement: if vitamin D deficiency the cause:

- Weekly loading: 25,000-50,000 IU weekly for 6-8 weeks. Then daily dosing

- Daily dosing: 800-2000 IU per day.

- Alternate day rapid loading regimens available

- Magnesium replacement: if hypomagnesaemia the cause:

- Intravenous: magnesium sulphate 2-5 g (1g = 4 mmol) in 100-250 mls of normal saline over 1-4 hours (always follow local policy and requires cardiac monitoring)

- Oral: Magnesium glycerophosphate 2 tablets (1 tablet = 4 mmol) three times a day, OR Magnesium aspartate 6.5g sachet (1 sachet = 10 mmol) twice a day.

Severe hypocalcaemia (< 1.9 mmol/L or symptomatic at any level)

- Give intravenous calcium gluconate: 10ml of 10% calcium gluconate in 100mls 0.9% sodium chloride or 5% dextrose over 10-20 mins. Can be given neat over 3 minutes if required. Needs cardiac monitoring.

- Consider repeat dose: repeated doses can be given until asymptomatic.

- Follow-up infusion: 100 mls of 10% calcium gluconate in 1L of 0.9% sodium chloride or 5% dextrose. This should be given at a rate of 50-100 ml/hour. Adjust based on response, continue cardiac monitoring.

- Calcium monitoring: calcium should be checked after 1-2 hours of initial dose and then monitor 4-6 hourly.

- Treat co-existent pathology: replace vitamin D or magnesium if deficiency identified.

Chronic hypocalcaemia

Patients with chronic hypocalcaemia require investigation into the underlying cause, common causes include CKD or vitamin D deficiency. In these cases, treatment of the underlying cause and management with vitamin D supplementation is usually sufficient. Patients with CKD may require additional measures due to secondary hyperparathyroidism.

Last updated: May 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback