Lung cancer

Notes

Introduction

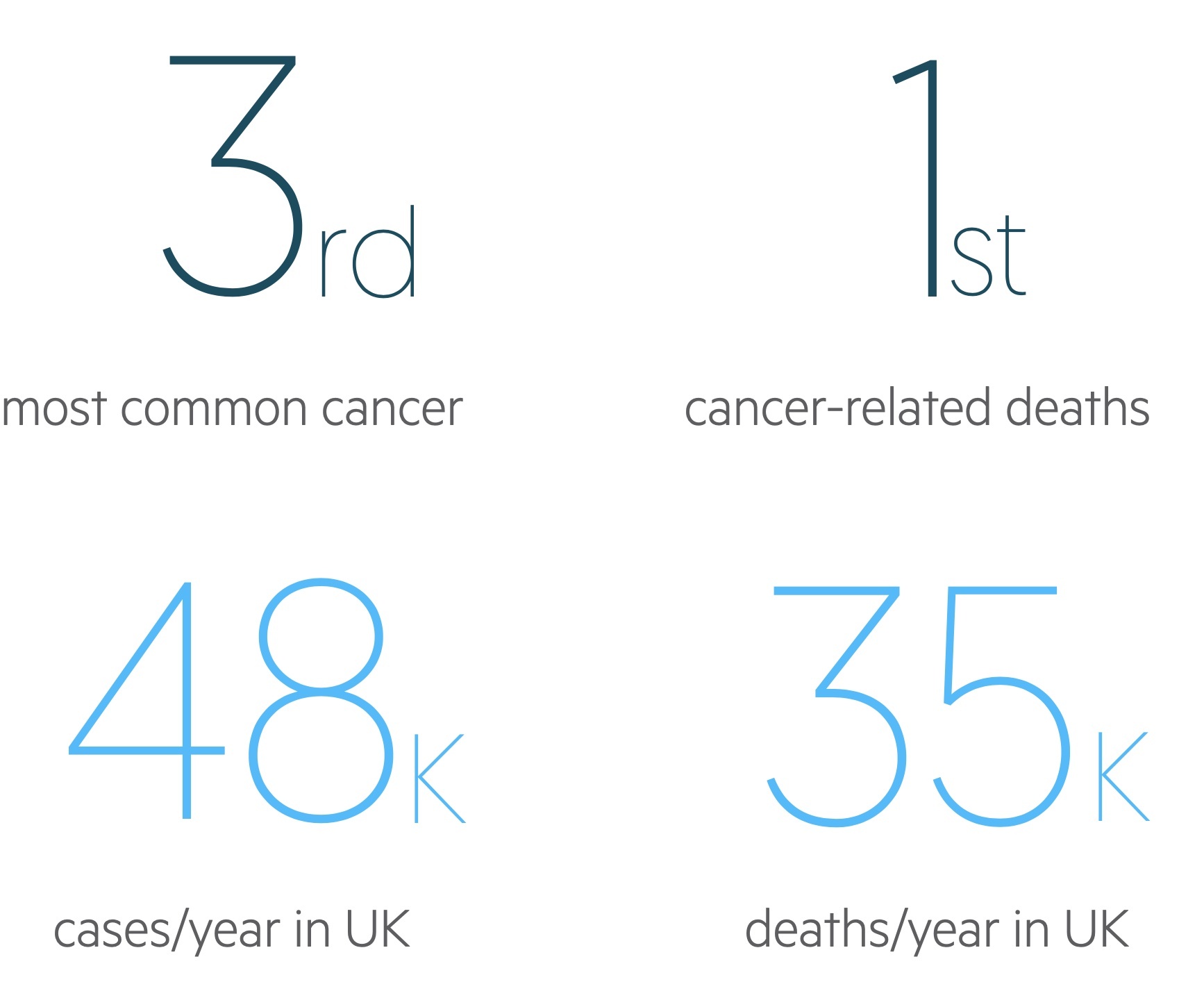

Lung cancer is a common malignant tumour, with around 48,500 cases diagnosed in the UK each year.

It is the third most common malignancy in the UK and is the leading cause of cancer-related death. Smoking is the most important aetiological factor, implicated in upwards of 80% of cases.

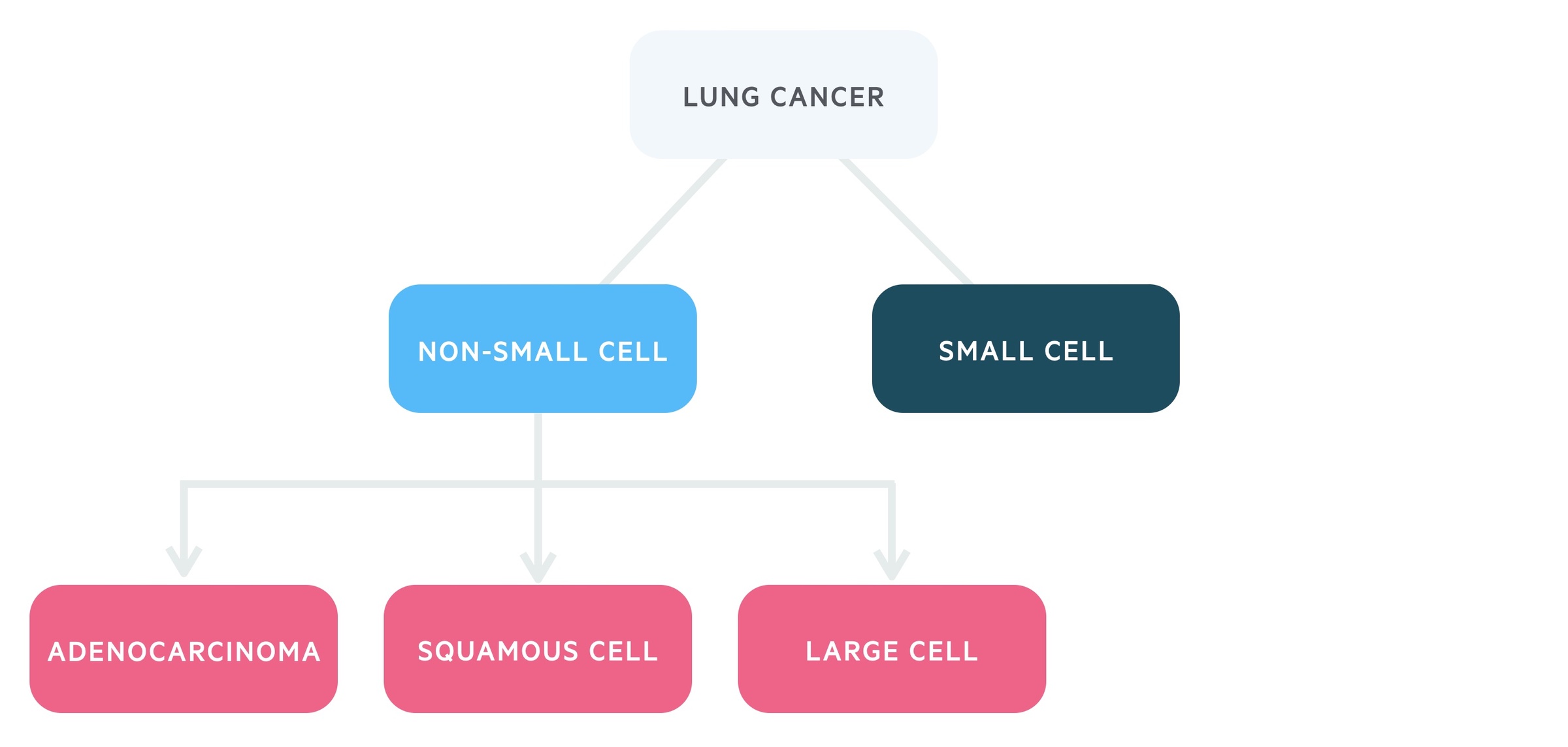

It is categorised by the underlying cell type:

- Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC)

- Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC):

- Adenocarcinoma

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Large cell

Management depends on the subtype, stage at diagnosis and patient co-morbidities. Broadly the options include chemotherapy, radiotherapy and surgical resection.

Figures from Cancer Research UK (last accessed Nov 2021).

Aetiology

Smoking is by far the most important aetiological factor. Exposure to other environmental agents can also increase the risk of developing lung cancer.

Smoking

Tobacco smoking is thought to be the cause of lung cancer in 80-90% of cases. Differences in gender mean women are somewhat less susceptible.

The effects of smoking remain long after cessation - the relative risk remains around two times that of a non-smoker at 30 years post-cessation.

Exposure

Asbestos, a fibrous building material, is perhaps the best-known carcinogen aside from tobacco. Unfortunately, Britain spent years as one of the largest importers of the material. Despite its use being illegal for decades in the UK, cases of asbestos-related disease are still seen as many of its effects appear after a lag.

Though more strongly associated with mesothelioma, asbestos is linked with adenocarcinoma of the lung. Tobacco and asbestos exposure act synergistically increasing the risk of cancer multiple times.

Radon gas, released from naturally occurring uranium, is also a recognised cause of lung cancer.

Pathophysiology

Lung cancers are divided by the cell type responsible, two broad categories exist, non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) and small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC).

Non-small cell lung cancer

Non-small cell lung cancer account for around 80-85% of lung cancers. Changing trends in incidence is a reflection of the timing of countries smoking epidemics.

1. Adenocarcinoma

Adenocarcinoma is now the most common form of lung cancer (around 38%). It is a cancer of the mucus-secreting cells.

Its incidence relative to other forms of lung cancer has shown an increase. It also appears proportionally more in non-smokers than squamous cell carcinoma. Smoking and asbestos exposure are both risk factors.

Adenocarcinoma tends to occur in lung peripheries.

2. Squamous cell

Squamous cell carcinoma is the second most common form of lung cancer (around 20%). Typically occurring in the central parts of the lungs, it can present with pneumonia secondary to an obstructed bronchus.

Smoking is the most common cause. Metastases tend to occur late and histopathology classically shows keratin.

3. Large cell

These are undifferentiated neoplasms accounting for around 5% of lung cancers. They tend to metastasise early.

Small cell lung cancer

SCLC accounts for around 15-20% of lung cancers and is considered separately due its fast doubling time, aggressive nature and early metastasis. SCLC is a cancer of the APUD cells, a neuroendocrine cell found in the lungs. It occurs almost exclusively in smokers.

It has an extremely poor prognosis, by the time of diagnosis curative therapy is rarely possible. SCLCs are commonly associated with paraneoplastic syndromes.

Clinical features

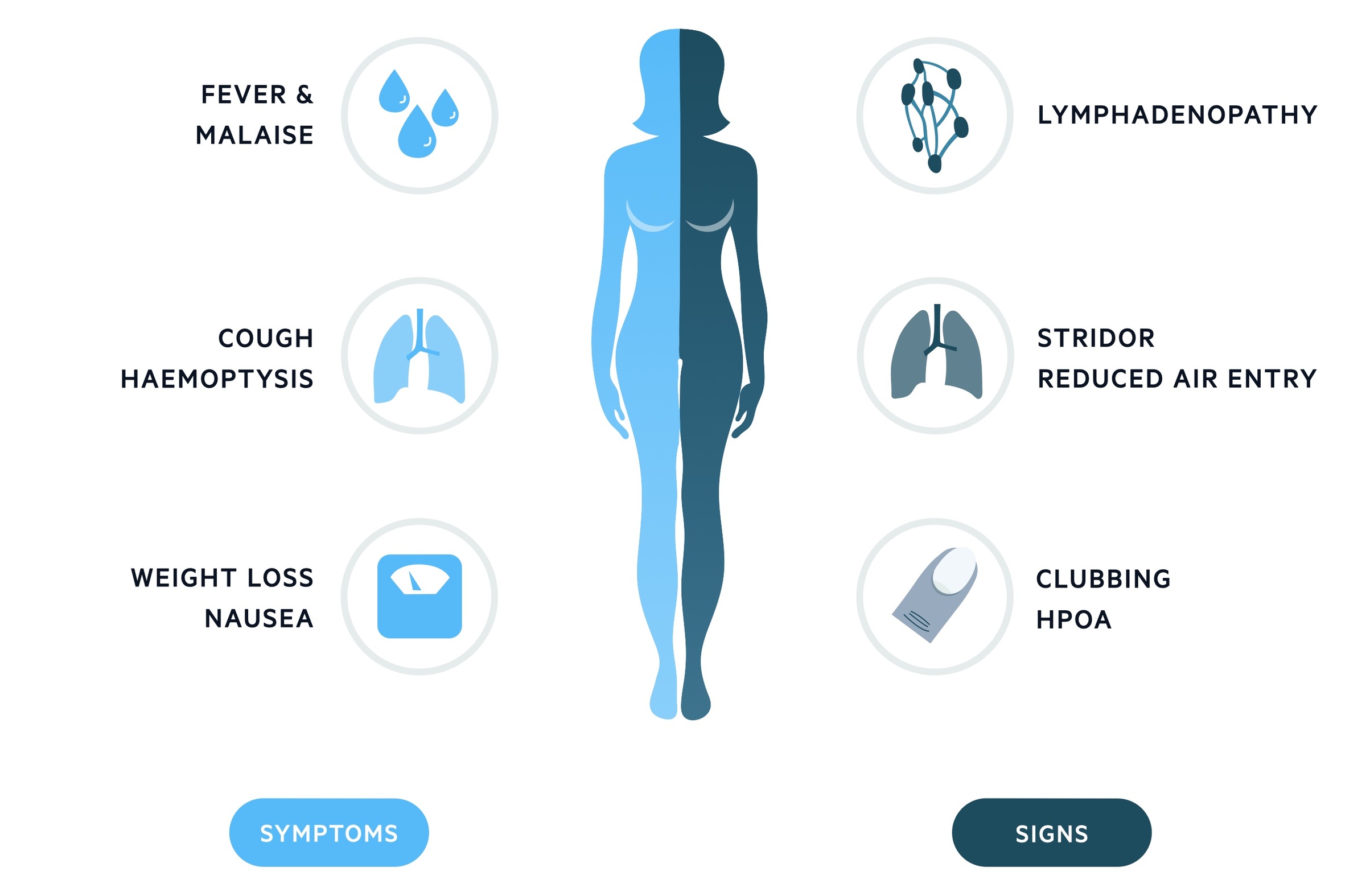

Lung cancer is frequently asymptomatic. When symptomatic, cough, malaise and weight loss predominate.

It may also present with haemoptysis, features of superior vena cava obstruction (SVCO) or a paraneoplastic syndrome (see chapter below). A higher index of suspicion is necessary for patients with a history of smoking.

Symptoms

- Fever

- Malaise

- Nausea

- Cough

- Haemoptysis

- Hoarseness (due to involvement of the recurrent laryngeal nerve)

- Weight loss

Signs

- Lymphadenopathy

- Stridor

- Wheeze

- Clubbing

- Hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy (HPOA): refers to a fibrovascular proliferation that results in periostitis of the long bones, arthralgia and clubbing. It is almost always secondary to another condition and there are many causes aside from lung cancer. For those interested read this article for more details.

- Signs of pleural effusion (exudative):

- Dull (‘stony dull') percussion

- Reduced vocal fremitus

- Reduced breath sounds

Superior vena cava obstruction

A tumour may cause compression of the superior vena cava. This causes engorgement of vessels in the neck and face, shortness of breath and a ‘fullness’ of the head.

See our SVCO notes for more information.

Pancoast tumour

This is a tumour of the pulmonary apex. Their location means local spread may affect the:

- Brachial plexus

- Cervical sympathetic trunk and the stellate ganglion

- Subclavian vein

Pancoast tumours are known to cause:

- Horner’s syndrome

- Pain in the shoulder that radiates into the arm and hand

- Atrophy of muscles of the upper limb

- Oedema of the upper limb

Metastasis

Metastasis may cause a variety of clinical features:

- Bone: bone pain, raised ALP

- Brain: focal and non-focal neurology

- Liver: abnormal LFTs

- Adrenal glands: though a common site of metastasis, normally asymptomatic

Paraneoplastic syndromes

Paraneoplastic syndromes refer to remote effects of tumours unrelated to mass effect, invasion or metastasis.

Hypercalcaemia

Hypercalcaemia may occur in lung cancers due to:

- Bony metastasis

- Tumour secretion of:

- Parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP)

- Calcitriol

Clinical manifestations of hypercalcaemia are often remembered by “stones, bones, groans, thrones, and psychiatric moans”. This refers to renal calculi, bone pain, abdominal pain, polyuria and signs of altered mental status. Hypercalcaemia is common in lung carcinoma, seen in approximately 50% of patients with squamous cell carcinoma, 20% of adenocarcinoma and 15% of small cell carcinoma.

See our Hypercalcaemia notes for more details.

SIADH

The syndrome of inappropriate anti-diuretic hormone (SIADH) is seen in around 10% of patients with SCLC. Symptoms are those of hyponatraemia and in extreme cases, cerebral oedema may occur.

See our SIADH notes for more details.

Cushing’s syndrome

Cushing’s syndrome is caused by exposure to high levels of glucocorticoids. In rare cases, lung cancers produce ectopic ACTH driving an increase in glucocorticoids.

See our Cushing's syndrome notes for more details.

Lambert-Eaton syndrome

This syndrome is caused by antibodies to voltage-gated calcium channels. It is seen in 1-3% of SCLC. It is characterised by both proximal and ocular muscle weakness.

Hypertrophic osteoarthropathy

This syndrome is characterised by clubbing and periostitis. It features a symmetrical, painful arthropathy affecting the distal joints.

Referral guidance

Patients with suspected lung cancer require two-week wait referral for further review.

NICE guidelines (NG 12): Suspected cancer: recognition and referral (published 2015, updated Jan 2021, last accessed Nov 2021) offer advice on referral for suspected malignancy. They advise two-week wait referral in patients with:

- Suggestive CXR findings

- Unexplained haemoptysis and aged over 40

Patients with evidence of SVCO or stridor require an urgent referral and emergency admission to hospital for further review.

Consider urgent CXR (within 2 weeks) in those aged over 40 with:

- Persistent or recurrent chest infection

- Clubbing

- Supraclavicular lymphadenopathy or persistent cervical lymphadenopathy

- Chest signs indicative of lung cancer

- Thrombocytosis

Offer an urgent CXR (within 2 weeks) in those aged over 40 with two of the following or have ever smoked and have one of the following:

- Cough

- Fatigue

- Shortness of breath

- Chest pain

- Weight loss

- Appetite loss

Investigations & diagnosis

Investigations look for evidence of a primary lung cancer, this involves imaging and tissue/cell sampling.

It is necessary to identify the cell type, the extent of invasion, nodal involvement and any metastasis.

Bloods

A routine blood screen should be ordered in all patients. Deranged liver function tests (LFTs) should prompt suspicion of liver metastasis. Calcium (measured in the bone profile) can be elevated in patients with malignant hypercalcaemia or bony metastasis.

- FBC

- U&Es

- LFTs

- Bone profile

Imaging

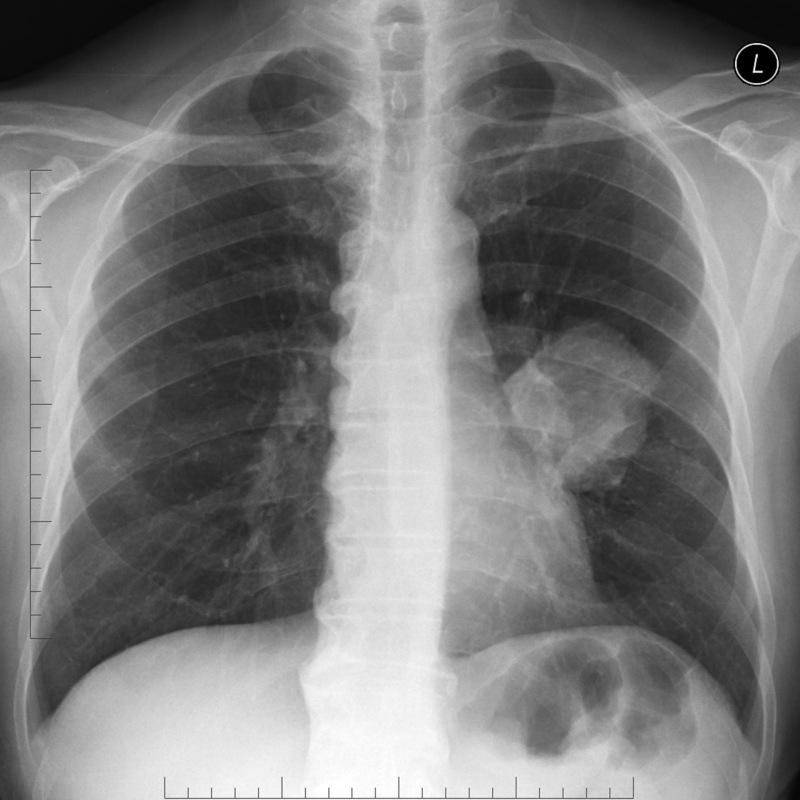

- Chest X-ray: is often used as initial screening (see referral above) and can also pick lesions incidentally. Signs of lung cancer on CXR include:

- Focal lesion

- Pleural effusion

- Widened mediastinum (indicative of enlarged nodes)

- CT chest (+ neck and upper abdomen): ordered in patients with significant suspicion of lung cancer or a suggestive CXR. Typical findings are a solitary pulmonary nodule with irregular or spiculated (looks like spikes coming out of the surface of the lesion). It may also show lymph node involvement or invasion. To help with staging the CT should include the neck and the upper abdomen (to look for liver or adrenal metastasis).

- PET-CT: positron emission tomography (combined with CT) involves the injection of a radioactive tracer, for example, fluorodeoxyglucose-18 (FGD-18). FGD-18 is a radiolabelled glucose taken up preferentially into more metabolically active cells - this includes cancers. It can be used to help with the radiological staging of disease.

- CT/MRI brain: can be ordered to exclude cerebral metastasis.

Large left-sided perihilar mass suspicious for lung cancer

Image courtesy of Assoc Prof Frank Gaillard and Radiopaedia

Special

- Bronchoscopy (+/- endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration or 'EBUS-TBNA'): bronchoscopy involves a thin long camera that enters the trachea and bronchial tree via the mouth. It allows for visualisation of the airways and any lesions that may be impinging or invading them. It also allows for washings/brushings to be taken for cytological analysis. In EBUS-TBNA an ultrasound probe is passed into the trachea and bronchial tree via the mouth. It allows for ultrasound-guided biopsy of paratracheal (next to the trachea) and peri-bronchial intra-parenchymal (near the bronchial tree within the lung) lung lesions.

- Lung function tests: this is typically ordered pre-operatively in patients undergoing lung resection for cancer. It allows clinicians to estimate if the patient will have sufficient residual lung capacity following a wedge resection (a wedge of the lung with tumour removed), a lobectomy (an entire lobe is removed) or pneumonectomy (removal of a whole lung). This is of particular importance in patients with pre-existing lung disease (e.g. emphysema) as they will already have reduced lung function.

Histology and cytology

Tissue biopsy:

- Obtained via bronchoscopy, image-guided biopsy, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) and/or mediastinoscopy.

- Obtained from the tumour, lymph node or metastasis.

Cytology:

- From aspirates, washings, pleural fluids.

- Obtained from the tumour, lymph node or metastasis.

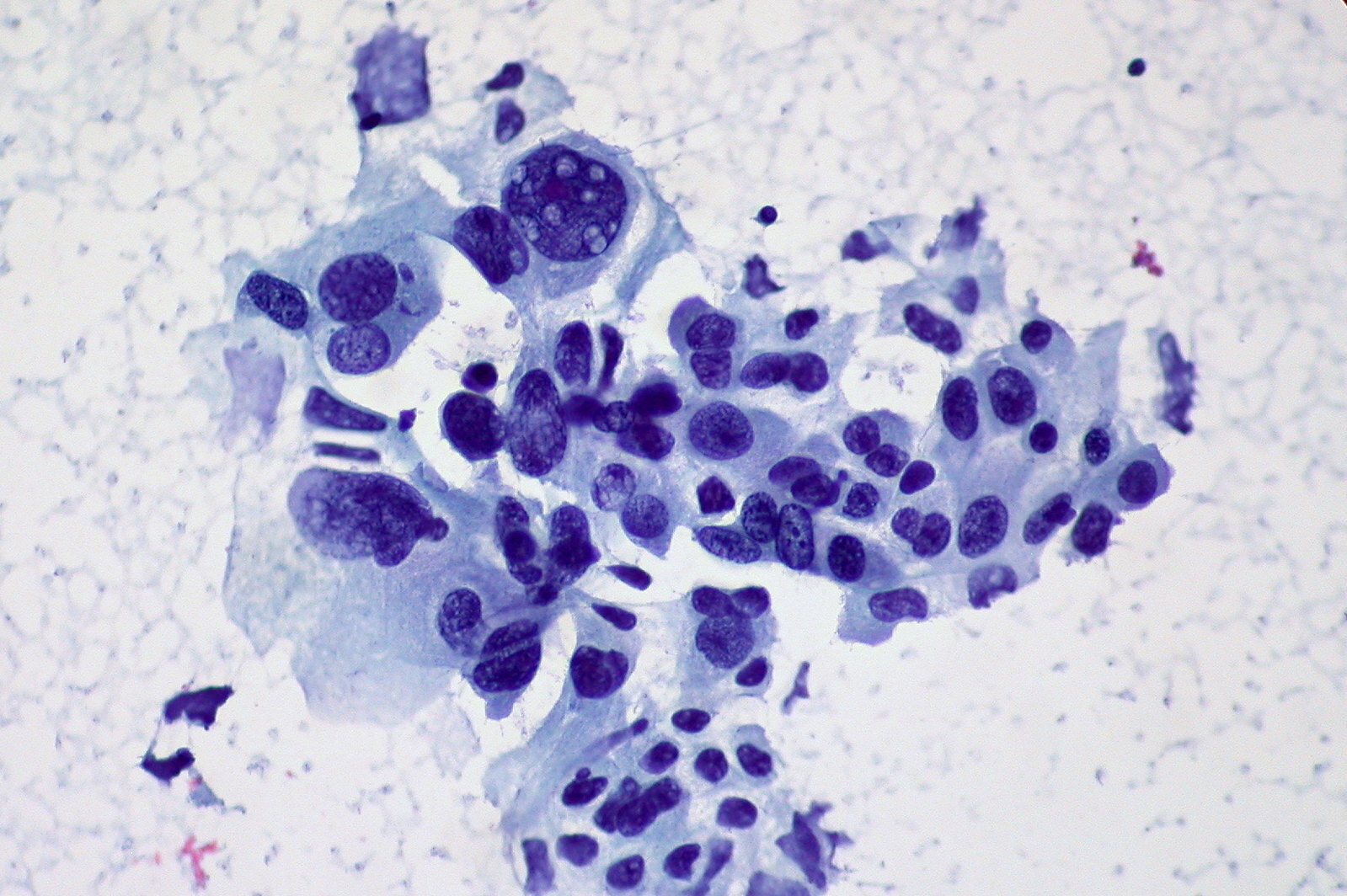

Cytology showing non-small cell carcinoma of the lung

Image courtesy of Ed Uthman

TNM staging

Staging helps guide management as well as providing prognostic information.

NSCLC is staged using the tumour node metastasis (TMN) staging system (based upon IASLC 8th Edition Lung Cancer TNM staging guidelines). SCLC may also be staged this way, though the VALSG staging system (see chapter below) may be used instead/in conjunction with it.

Tumour

- TX: Primary tumour cannot be assessed or tumour proven by presence of malignant cells in sputum or bronchial washings but not visualised by imaging or bronchoscopy

- T0: No evidence of a primary tumour

- Tis: Carcinoma in situ

- T1: Tumour measuring 3 cm or less in greatest dimension surrounded by lung or visceral pleura without bronchoscopic evidence of invasion more proximal than the lobar bronchus (i.e. not in the main bronchus)

- T1a: tumor ≤1 cm

- T1b: tumor >1 cm but ≤2 cm

- T1c: tumor >2 cm but ≤3 cm

- T2: Tumour > 3 cm but ≤ 5 cm or tumour with any of the following features:

- Involves the main bronchus regardless of distance from the carina but without the involvement of the carina

- Invades visceral pleura

- Associated with atelectasis or obstructive pneumonitis that extends to the hilar region involving part or all of the lung

- T2a: tumour > 3 cm but ≤ 4 cm in greatest dimension

- T2b: tumour > 4 cm but ≤ 5 cm in greatest dimension

- T3: Tumour > 5 cm but ≤ 7 cm in greatest dimension or associated with separate tumour nodule(s) in the same lobe as the primary tumour or directly invades any of the following structure:

- Chest wall (including the parietal pleura and superior sulcus)

- Phrenic nerve

- Parietal pericardium

- T4: Tumour > 7 cm in greatest dimension or associated with separate tumour nodule(s) in a different ipsilateral lobe than that of the primary tumour or invades any of the following structures: diaphragm, mediastinum, heart, great vessels, trachea, recurrent laryngeal nerve, oesophagus, vertebral body or carina)

Node

- Nx: Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed

- N0: No regional lymph node metastasis

- N1: Metastasis in ipsilateral peribronchial and/or ipsilateral hilar lymph nodes and intrapulmonary nodes, including involvement by direct extension

- N2: Metastasis in ipsilateral mediastinal and/or subcarinal lymph node(s)

- N3: Metastasis in contralateral mediastinal, contralateral hilar, ipsilateral or contralateral scalene, or supraclavicular lymph node(s)

Metastasis

- M0: no distant metastasis

- M1: distant metastasis present

The above tumour, node and metastasis classification can then be grouped into stages:

Stage I:

- IA: T1N0M0

- IIB: T2aN0M0

Stage II:

- IIA: T2bN0M0

- IIB: T1N1M0, T2N1M0, T3N0M0

Stage III:

- IIIA: T1N2M0, T2N2M0, T3N1M0, T4N0M0, T4N1M0

- IIIB: T1N3M0, T2N3M0, T3N2M0

- IIIC: T3N3M0, T4N3M0

Stage IV: Any T, Any N, M1

VALSG staging

SCLC may be staged in a more simple two stage system named VALSG staging. It is felt this better reflects the limited opportunities for treatment with curative intent.

Limited disease: tumour not spread beyond hemithorax, regional nodes that may be treated with single radiotherapy field.

Extensive disease: tumour spread beyond hemithorax or extensively through the hemithorax, distant metastasis, malignant effusions or contralateral hilar/supraclavicular involvement.

Management

Management is guided primarily by the cancers cell type, staging and the patients performance status.

Care is guided by an appropriate MDT. Patients will require help and support coming to terms with their diagnosis and to understand, and best choose from, the treatment options available to them.

As a student there are a number of key management options to be aware of:

- Smoking cessation: patients who are still smoking should be given support to quit. This still has the potential to improve their long-term outcomes, particularly in those undergoing surgery where it reduces the risk of postoperative pulmonary complications.

- Surgical resection: this represents the mainstay of treatment for patients with potentially curative disease. Operations can be via a thoracotomy (large incision, open procedure) or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). VATS is 'key-hole' procedure that is commonly used and can be thought of as similar to laparoscopy in the abdomen. It differs as the space is achieved not by the insufflation of gas (as in laparoscopy) but through deflation of the lung. Finally, robotics are slowly entering the field and may be used in some centres. The main options for surgical resection are:

- Wedge resection: a 'wedge' of tumour containing lung is removed

- Lobectomy: an entire lobe of the lung is removed

- Pneumonectomy: an entire lung is removed.

- Radiotherapy: radiotherapy involves beaming intense targeted radiation at the tumour. It can be used with radical intent (i.e. potentially curative) as an alternative to surgery in early-stage NSCLC. It can also be used as a combination with chemotherapy (that can follow surgery) or alone for both NSCLC and SCLC.

- Chemotherapy: chemotherapy, often cisplatin-based, is commonly used. It may be used as adjuvant therapy (following surgery for NSCLC) to increase the chance of cure. It may also be used in those with SCLC.

- Systemic anti-cancer therapy (SACT): these are specific therapies used in non-squamous NSCLC (i.e. adenocarcinoma, large cell undifferentiated). They are indicated for patients with specific identifiable mutations that demonstrate a predisposition to a certain treatment. There are many types and it is not likely you will be expected to recite them as a student but it is worth being aware of them. Here are two examples:

- Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase (EGFR-TK) mutation: treatment options include afatinib, erlotinib and gefitinib. These are all EGFR-TK inhibitors.

- Anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive (ALK) gene rearrangement: treatment options include crizotinib, ceritinib and alectinib. These are all ALK inhibitors.

NSCLC

Surgical resection (normally lobectomy) is the treatment of choice in those where it is potentially curative (e.g. stage I-II). Radical radiotherapy can be used where surgery is not suitable or declined.

Adjuvant chemotherapy is used in combination with surgery or given as a palliative therapy to improve survival in more advanced disease. SACTs (as described above) are often used in non-squamous NSCLC.

SCLC

Surgical resection is only an option in early disease, appropriate in < 5% of cases. In T1/2a N0 M0 disease surgery with curative intent may be utilised.

Generally, treatment consists of chemotherapy (often cisplatin-based) and/or radiotherapy with the goal of extending survival and reducing troublesome symptoms.

Prognosis

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death in the UK.

In the UK the overall survival is (figures from Cancer Research UK):

- One-year survival: 40.6%

- Five-year survival: 16.2%

Prognosis is highly dependent on age and stage at time of diagnosis. Almost half survive 5-years if aged 15-39 whilst just 5 in 100 of those over 80 survive that long. When diagnosed at the earliest stage 88% survive one-year or more compared with 19% diagnosed at the latest stage.

Last updated: April 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback