Trigeminal neuralgia

Notes

Overview

Trigeminal neuralgia is characterised by episodes of acute severe facial pain within the distribution of the trigeminal nerve.

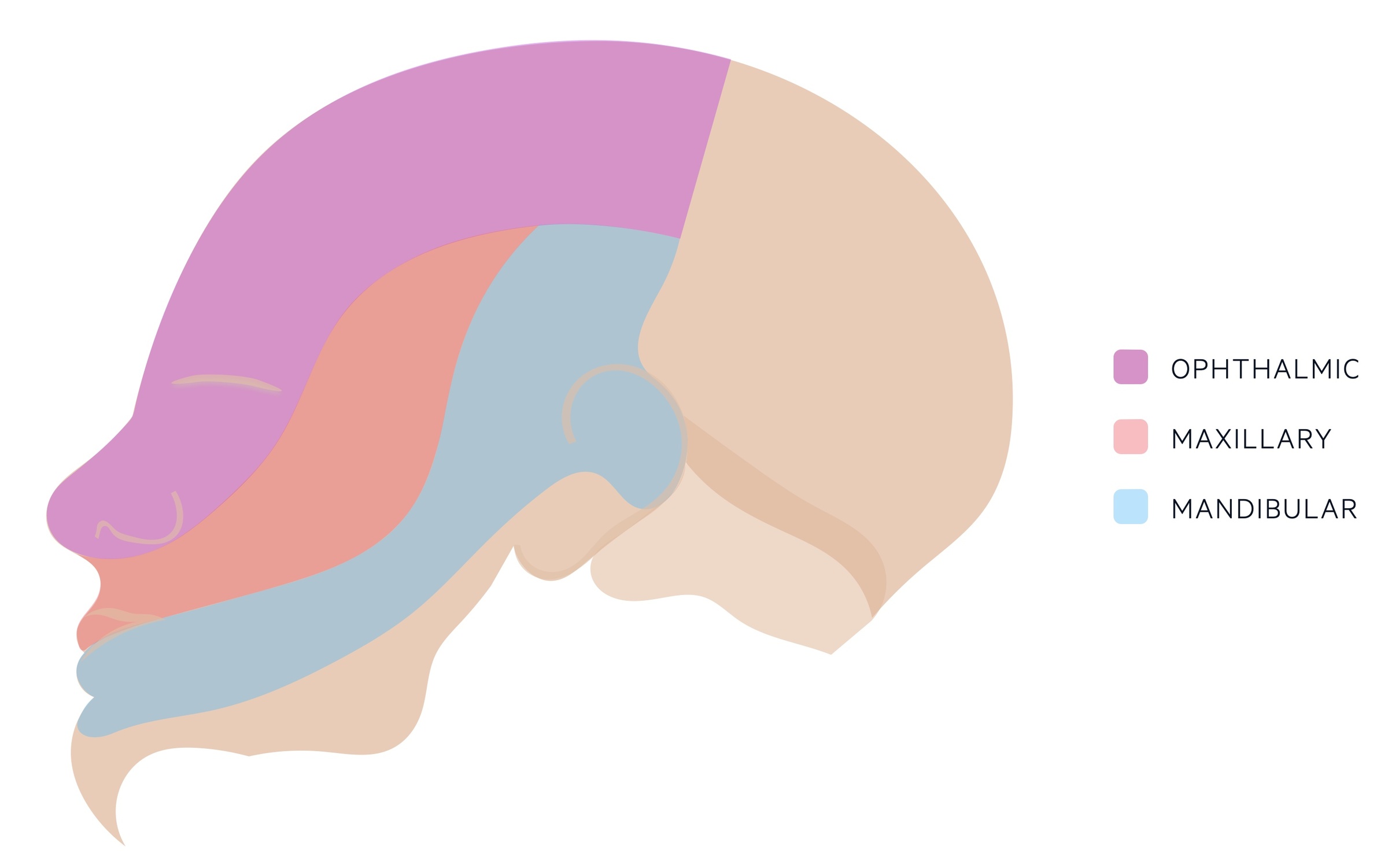

Once termed tic douloureux, trigeminal neuralgia is a rare condition that most commonly affects the maxillary and mandibular branches of the trigeminal nerve.

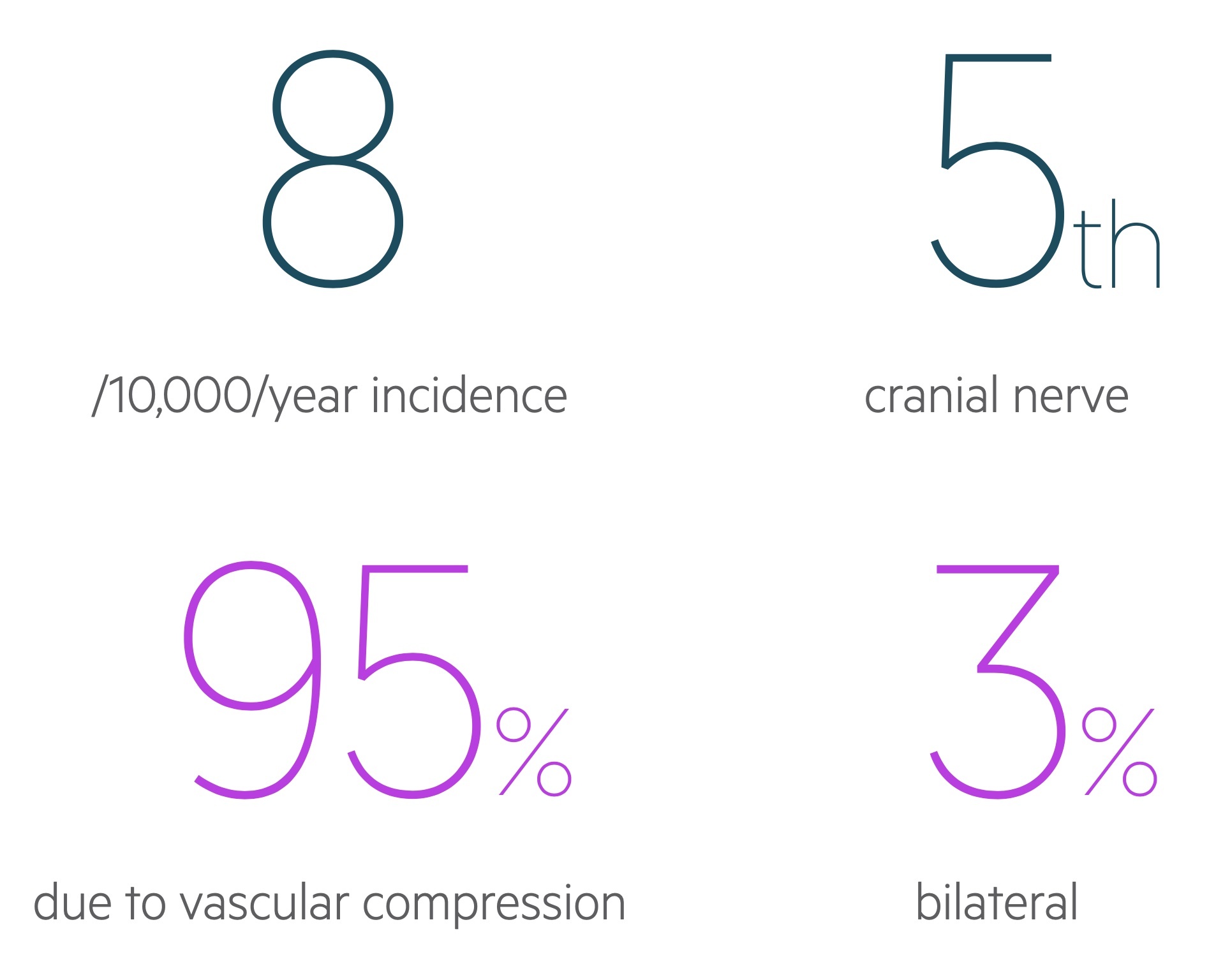

Episodes normally last seconds to a few minutes and may be triggered by cold wind, talking, vibrations Typically the condition is unilateral though it is bilateral in 3%.

Epidemiology

Trigeminal neuralgia is a rare condition that is more common in women.

The exact incidence of trigeminal is unclear. Annual incidence in the UK is estimated to be 8 per 10,000 although due to its rarity these estimations can vary wildly. It is around twice as common in women compared to men.

Trigeminal nerve

The trigeminal nerve is the 5th cranial nerve.

The trigeminal nerve is composed of three major branches:

- Ophthalmic nerve (V1): general somatic afferent. Exits the skull via the superior orbital fissure and provides sensation to the to forehead, anterior scalp, nose and eyes (including conjunctiva).

- Maxillary nerve (V2): general somatic afferent. Exits the skull via the foramen rotundum. Provides sensation to the mid-face, lower eyelid, nasal cavity, palate, upper lip and maxillary teeth.

- Mandibular nerve (V3): general somatic afferent and branchial (special visceral) efferent. Exits the skull via the foramen ovale. Provides sensation to part of scalp, part of the ear, lower face, tongue, floor of mouth and mandibular teeth. Provides motor input to the muscles of mastication (temporalis, masseter, medial and lateral pterygoids) and the tensor tympani.

Aetiology

Vascular compression is the most common cause of trigeminal neuralgia.

Primary trigeminal neuralgia

Primary trigeminal neuralgia refers to disease caused by vascular compression. It is thought to account for 80-95% of cases of trigeminal neuralgia. This normally occurs near the root of the nerve at the ‘nerve root entry zone’. The compression is thought to lead to demyelination and abnormal electrical activity in response to stimuli.

Secondary trigeminal neuralgia

Secondary trigeminal neuralgia refers to disease occurring secondary to another condition. Compression may be caused by other lesions (e.g. vestibular schwannoma, meningioma, cysts).

Multiple sclerosis can also lead to secondary trigeminal neuralgia due to demyelination of the trigeminal nerve.

Idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia

As the name suggests trigeminal neuralgia may occur without an identifiable cause.

Risk factors

Women are more commonly affected by trigeminal neuralgia and incidence increases with advancing age.

- Female sex

- Advancing age

- Multiple sclerosis

- Family history

Clinical features

Patients describe short-lived episodes of electric shock pain in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve.

Classical presentation

Patients typically describe a history of unilateral severe episodic pain in the trigeminal distribution (normally maxillary, mandibular or both) that lasts seconds to minutes before resolving. Patients often characterise the pain as ‘electric shock’ like. It can occur bilaterally though this is rare and considered a red flag (see below).

The attacks are recurrent and there may be triggers such as cold air or eating. Remission can occur with symptoms disappearing for long periods before recurring.

Red flags

Clinicians must be aware that similar symptoms may be seen in other conditions including malignancy. In general, younger onset (<40 years), bilateral onset, hearing difficulties, or optic neuritis are all concerning features that require investigation for an alternative cuase, particularly something like multiple sclerosis.

Diagnostic criteria

The International Classification of Headache Disorders, third edition formally defines the clinical diagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia.

Recurrent paroxysms of unilateral facial pain in the distribution(s) of one or more divisions of the trigeminal nerve, with no radiation beyond, and fulfilling criteria 2 and 3.

- Pain has all of the following characteristics:

- Lasting from a fraction of a second to 2 minutes

- Severe intensity

- Electric shock-like, shooting, stabbing or sharp in quality

- Precipitated by innocuous stimuli within the affected trigeminal distribution

- Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis

Taken from ICHD, third edition.

Management

Carbamazepine forms the mainstay of management.

Urgent referral

Clinical judgement must be used - urgently refer any patient with a suspected secondary cause or in whom an alternative diagnosis is considered. Some red flags are described in the ‘Clinical features’ section above. MRI tends to be the diagnostic investigation of choice in those with a suspected sinister cause.

Medical management

Carbamazepine forms the mainstay of management. Typically a starting dose of 100mg twice day is given and this may be titrated upward depending upon response. Once in remission the dose should be titrated down to the lowest level that maintains remission.

If ineffective, contraindicated or not tolerated patients should be referred to neurology. Second line options include:

- Gabapentin

- Lamotrigine

Surgical management

In patients in who medical management is ineffective surgical intervention may be considered. The options depend on the underlying aetiology and patient factors. For primary trigeminal neuralgia options include:

- Microvascular decompression

- Gamma knife radiosurgery

Prognosis

The course of trigeminal neuralgia is varied but normally characterised by episodes of attacks followed by remissions.

Most patients have a relapsing-remitting course though some patients experience a chronic background pain.

Patients may experience remissions that last many months. With time such remissions normally become shorter. Of those with a new diagnosis:

- 65% will have a further episode in 5 years

- 77% will have a further episode in 10 years

The majority of patients experience remission with medical therapy, though up to 10% will not respond.

Last updated: June 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback