TIA

Notes

Overview

Transient ischaemic attack is a cerebrovascular event that is caused by abnormal perfusion of cerebral tissue.

TIA is defined as transient neurological dysfunction caused by focal brain, spinal cord, or retinal ischaemia, without evidence of acute infarction. It is a medical emergency, within the first week following a TIA, the risk of stroke is up to 10%. The estimated incidence of TIA within the UK is 50 per 100,000 people per year.

Traditionally, transient neurological dysfunction with resolution within 24 hours was diagnostic of TIA. However, up to a third of patients whose symptoms have resolved within 24 hours have evidence of infarction on imaging. Consequently, the definition is now 'tissue-based' rather than 'time-based' with the incoporation of the phrase ‘without evidence of acute infarction’. Thus, the end-point is biological tissue damage, not an arbitrary time cut-off.

Aetiology & pathophysiology

TIA is caused by temporary blockage to blood flow, which leads to ischaemia.

Ischaemia refers to the absence of blood flow to an organ, which deprives it of oxygen. Cerebral ischaemia may be due to in situ thrombosis, emboli, or rarely, dissection.

- Thrombosis: local blockage of a vessel due to atherosclerosis. Precipitated by cardiovascular risk factors (e.g. hypertension, smoking) or small vessel disease (e.g. vasculitis, sickle cell).

- Emboli: propagation of a blood clot that leads to acute obstruction and ischaemia. Typically due to atrial fibrillation or carotid artery disease.

- Dissection: a rare cause of cerebral ischaemia from tearing of the intimal layer of an artery (typically carotid). This leads to an intramural haematoma that compromises cerebral blood flow. May be spontaneous or secondary to trauma.

During a TIA, there is a transient reduction in blood flow to an area of cerebral tissue that causes neurological symptoms. TIA commonly occurs secondary to embolisation from atrial fibrillation or carotid artery disease.

Risk factors

Risk factors for TIA are due to conditions that affect the integrity of vessels or increase the risk of embolisation.

TIA is a cardiovascular disease, and as such, it shares many common risk factors with conditions such as ischaemic heart disease and peripheral vascular disease.

- Smoking

- Diabetes mellitus

- Hypertension

- Hypercholesterolaemia

- Obesity

- Atrial fibrillation

- Carotid artery disease

- Age

- Thrombophilic disorders (e.g. antiphospholipid syndrome)

- Sickle cell disease

Clinical features

A TIA presents with sudden, focal neurological deficit that reflects the area of the brain devoid of blood flow.

A variety of neurological deficits can present in TIA, but the majority of symptoms will resolve within 1-2 hours.

Neurological deficit

- Unilateral weakness or sensory loss

- Dysphasia

- Ataxia, vertigo, or incoordination

- Amaurosis fugax: see below

- Homonymous hemianopia: visual field loss on the same side of both eyes

- Cranial nerve defects: particularly if associated with contralateral sensory/motor deficits

Amaurosis fugax

This is a classical syndrome of short-lived monocular blindness, which is often described as a black curtain coming across the vision. It is a term usually reserved for transient visual loss of ischaemic origin.

The principle cause of amaurosis fugax is transient obstruction of the ophthalmic artery, which is a branch of the internal carotid artery. However, other ischaemic causes to consider include giant cell arteritis (i.e. temporal arteritis) and central retinal artery occlusion. An important differential of transient visual loss, particularly in young patients, is migraine.

Diagnosis

Any patient with ongoing symptoms requires urgent referral to a stroke unit.

TIA is a clinical diagnosis based on the history as the majority of patients will have complete resolution of symptoms. Any patient with ongoing symptoms needs to be treated as an acute stroke and urgently referred to a stroke unit.

Key aspects to making the diagnosis of TIA include:

- Onset & duration of symptoms: collateral history may be needed

- Associated symptoms (suggest alternative diagnosis): headache, vomiting, syncope, seizures

- Neurological deficit: see clinical features

- Cardiovascular risk factors: hypertension, diabetes, smoking, high cholesterol, family history

- Co-morbidities: heart disease, atrial fibrillation, carotid disease, previous stroke/TIA

- Anticoagulation history

- Clinical examination: cardiovascular exam including BP, neurological examination, fundoscopy

NOTE: patients on anticoagulation with new neurological deficits require urgent admission and exclusion of intracerebral bleeding

The Face Arm Speech Time Test (FAST test)

A rapid diagnostic screen to assess for features of TIA/stroke used in the community. Anyone with a positive screen should be assessed urgently at a stroke unit. The test is positive if any of the following are met:

- New facial weakness

- New arm weakness

- New speech difficulty

Differential diagnosis

Numerous conditions can present similarly to TIA, which are collectively referred to as ‘stroke mimics’.

- Toxic/metabolic: hypoglycaemia, drug and alcohol consumption

- Neurological: seizure, migraine, Bell’s palsy

- Space occupying lesion: tumour, haematoma

- Infection: meningitis/encephalitis, systemic infection with ‘decompensation’ of old stroke

- Syncope: extremely uncommon presentation of TIA, many causes

Referral

All patients with a suspected TIA should be referred to a specialist TIA clinic and be seen within 24 hours.

At the TIA clinic, patients should have a comprehensive medical assessment including blood tests, electrocardiogram (ECG) and imaging. If the episode occurred > 1 week ago, the assessment should be within 7 days.

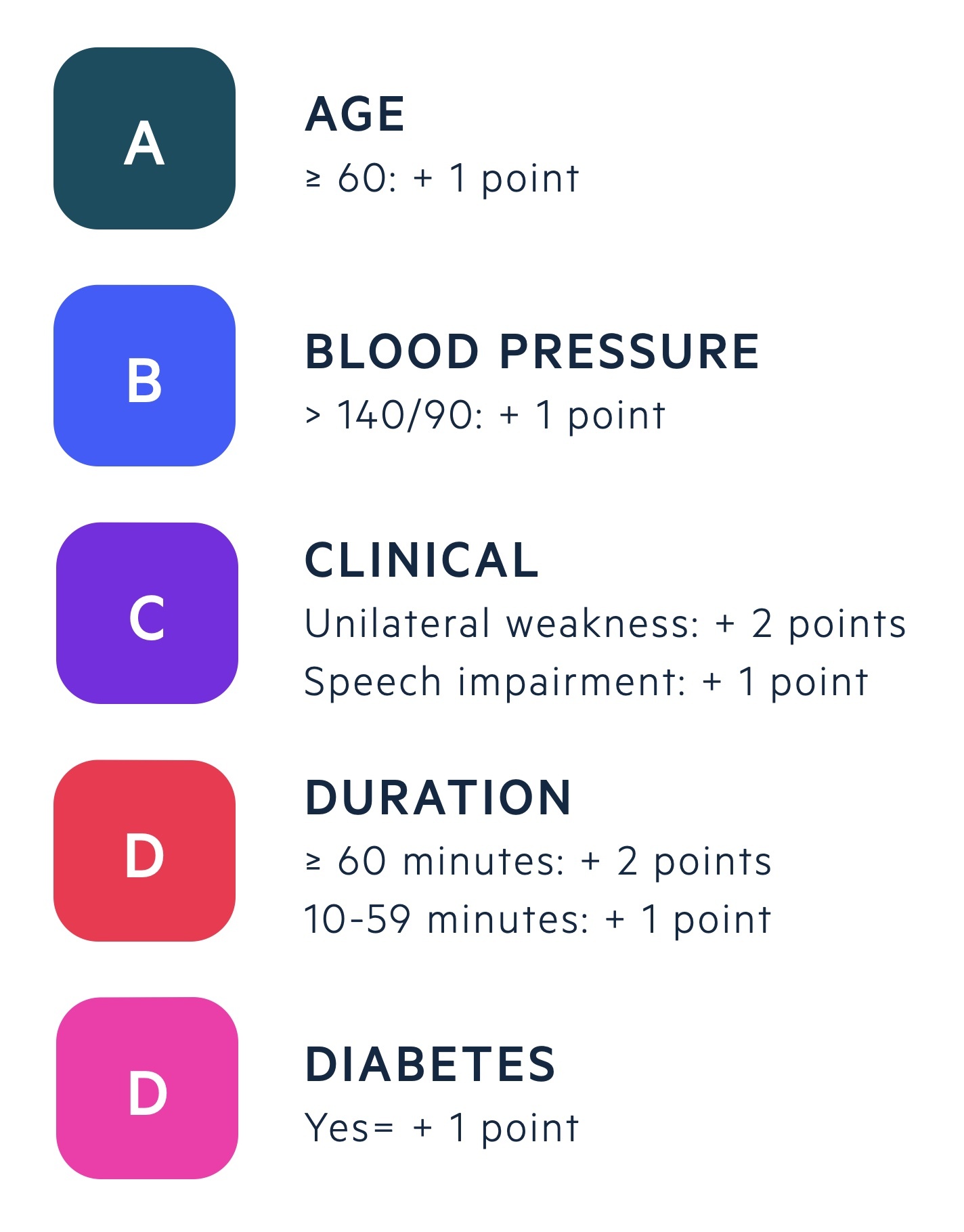

The ABCD2 is a prognostic score that was traditionally used to identify people at high risk of stroke after a TIA score. It was originally used to triage the urgency of TIA referrals and treatment with aspirin. NICE no longer recommend its use.

Investigations

MRI is the key investigation in a patient with suspected TIA.

Bloods

- Haematology: full blood count (FBC), HbA1c +/- haemoglobin electrophoresis

- Routine biochemistry: Urea & electrolytes (U&Es), bone profile, liver function tests (LFTs), lipid profile

- Coagulation: routine clotting

- Special (as indicated): ‘young stroke screen’ (e.g. thrombophilia screen, Fabry’s)

Cardiac investigations

- ECG: assessment for arrhythmias, especially atrial fibrillation

- Echo: not routinely offered unless suspicion of heart disease or confirmed stroke

Imaging

- MRI head with diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI): preferred to CT unless alternative diagnosis suspected that CT could detect. Enables detection of small infarcts.

- Carotid dopplers: all patients who are candidates for carotid endarterectomy.

Urgent admission

Certain features warrant urgent admission to hospital because of the high risk of stroke, bleeding or deterioration.

- ≥1 suspected TIA (crescendo TIA): typically within the last 7 days

- Suspected cardioembolic source or severe carotid stenosis

- Vulnerable patient: lack of reliable observer at home to monitor for worsening symptoms

- Bleeding disorder or taking an anticoagulant

Any patient with ongoing symptoms needs to be treated as an acute stroke and urgently referred to a stroke unit.

Management

Any patient with a suspected TIA should be treated with 300 mg of aspirin unless contraindicated.

The management of TIA can be divided into acute treatment, secondary prevention and lifestyle measures.

Acute treatment

The principle management for TIA is 300 mg of aspirin that is usually continued for two weeks. This is followed by treatment with 75 mg of clopidogrel as long-term vascular prevention.

Patients with atrial fibrillation or significant carotid artery disease require a different treatment pathway.

- Atrial fibrillation (AF): should be offered and counselled about starting an oral anticoagulant

- Carotid artery disease (CAD): urgent referral for consideration of carotid endarterectomy if significant disease. Based on NASCET or ECST criteria for stenosis.

- NASCET: 50-99% stenosis

- ECST: 70-99% stenosis

Secondary prevention

Patients with a TIA should be offered secondary prevention treatments to optimise their cardiovascular risk

- Anti-hypertensives: as per hypertension guidelines (tolerate higher if significant bilateral CAD)

- Lipid modification: offer high-dose statin therapy unless contraindication.

- Diabetic control: treat any new diagnosis of diabetes and optimise control of pre-existing disease

- Obstructive sleep apnoea: referral to specialist sleep medicine/respiratory clinic if suspected

- Pre-menopause: use of combined oral contraceptive pill contraindicated.

Lifestyle measures

Basic advice on physical activity, smoking cessation, diet optimisation and alcohol intake should be given to all patients

Driving

It is vital to advise all patients to stop driving if they have had a suspected, or confirmed, TIA.

Patients should always be advised to check the DVLA for the most up to date recommendations on driving.

- Cars and motorcycles: stop driving one month, do not need to inform DVLA

- Larger vehicles (e.g. buses, lorries): stop driving, inform the DVLA

Last updated: October 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback