Myasthenia gravis

Notes

Overview

Myasthenia gravis is a neuromuscular disorder, which is characterised by weakness and fatiguability.

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is a relatively uncommon autoimmune disorder, which is due to antibody-mediated blockage of neuromuscular transmission.

MG is predominantly due to the formation acetylcholine receptor antibodies (AChR-Ab) that bind to acetylcholine (ACh) receptors at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ). This prevents binding of ACh and subsequent depolarisation needed for muscular contraction. The hallmark of MG is fatiguability, which refers to increasing muscle weakness with repeated use.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of MG is estimated at 15 per 100,000 population within the UK.

MG has a variable annual incidence of 7-23 per million people. The prevalence of the condition has been increasing over the last few decades with improved mortality, better recognition and ageing population.

MG can occur at any age and it has a bimodal peak in incidence:

- 2nd-3rd decade of life: predominantly females

- 6th-7th decade of life: predominantly males

There are rare forms of neonatal MG due to transplacental passage of the AChR-Ab (transient MG) or congenital MG due to genetic mutations.

Aetiology

Approximately 80-90% of cases of MG are due to the formation of AChR-antibodies.

MG is considered an acquired autoimmune disorder due to the formation of AChR-Ab by B lymphocytes. The reason patients develop this autoantibodies is unknown.

The AChR antibodies are typically polyclonal IgG1 and IgG3 antibodies, which block the ACh receptor at the NMJ of skeletal tissue. In addition, they fix complement and accelerate the turnover of these receptors leading to reduced number. Due to the heterogeneity of the ACh receptor, there is marked variability between patients and even between muscle groups of the same patient. The AChR-Ab level does not generally correlate with disease severity.

Thymus gland

The majority of patients with MG secondary to AChR-Abs have evidence of thymic abnormalities. The thymus is a bilobed lymphoid organ important in the development of T lymphocytes (i.e. T cells), which is situated in the anterior superior mediastinum of the thorax.

Immature T cells migrate to the thymus from the bone marrow and undergo maturation. During this process positive and negative selection are essential to ensure T cells can detect its own cells from foreign and that any cells with high autoreactivity are eliminated (i.e. react strongly to self-antigens). These mechanisms are thought to be important in the development of autoimmune disease.

In MG, 10-15% of patients have a thymoma (rare benign tumour of thymus gland) and up to 85% have thymic hyperplasia. The disease may even improve or regress with removal of the thymus gland.

Myoid cells

The importance of the thymus in MG is related to myoid cells. Myoid cells in the thymus resemble skeletal muscle cells and even possess the ACh receptor. It is thought these cells are central to the development of autoimmunity to ACh receptors. For these reasons, investigating for thymic abnormalities is critical in MG and many patients may be offered surgical removal.

Other factors

Several genetic factors have been implicated in the development of MG including human leucocyte antigens (HLA) HLA-B8, DRw3, and DQw2, which are involved in antigen presentation.

Additionally, MG is associated with other autoimmune diseases including Graves’ disease, systemic lupus erythematous, and rheumatoid arthritis, among others.

Pathophysiology

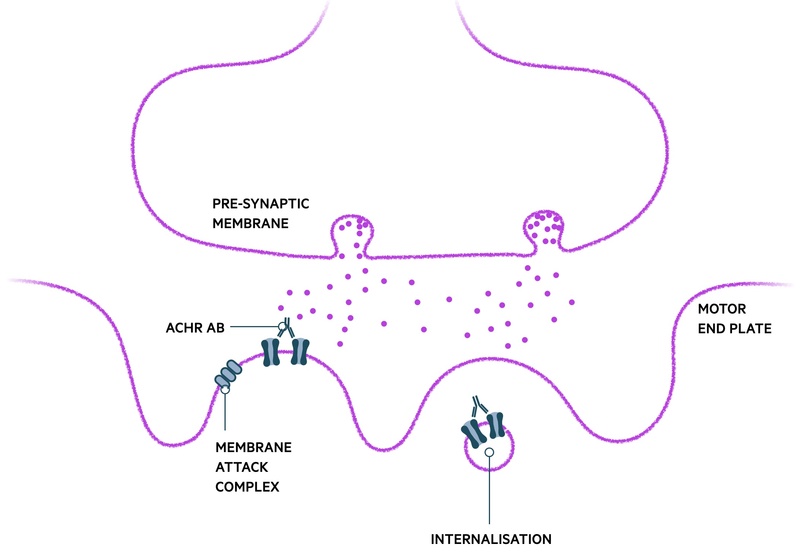

The neuromuscular junction is the principle site of pathology within MG.

The NMJ is important for excitation-contraction coupling. This refers to the process of converting an action potential that terminates at a NMJ, which is a chemical synapse between motor neuron and muscular fibre, into muscular contraction.

Neuromuscular junction

During normal functioning, an action potential travels down a nerve to a NMJ junction, which is composed of a pre-synaptic membrane, synaptic cleft and motor-end plate. The motor-end plate is formed by a thickened portion of the muscle plasma membrane known as the sacrolemma. The sequential steps involved include:

- Presynaptic depolarisation: action potential passes to pre-synaptic membrane.

- Calcium ion influx: action potential activates calcium channels.

- Exocytosis: stored vesicles of ACh released into synaptic cleft.

- ACh binds receptor: ACh binds to its receptor on the sarcolemma.

- Opening of ACh-R: confirmational change leads to sodium influx and depolarisation.

- Sodium-channel activation: leads to depolarisation of adjacent muscle.

- T-tubules: depolarisation invades the ’T-tubules’ of muscles. Activates calcium channels.

- Calcium ion influx: influx calcium ions leads to mechanical contraction.

Following activation, ACh is broken down by the enzyme acetylcholinesterase, which prevents further depolarisation. ACh is broken down into choline and acetic acid of which choline is taken back into the pre-synaptic bulb. In the bulb, choline is bound to acetyl CoA by choline acetyltransferase and reformed into vesicles to be released during another action potential.

Pathogenesis in MG

In MG, AChR-Abs bind to ACh-R on the motor end-plate of skeletal muscle, which blocks the binding of ACh. This is an example of a type II hypersensitivity reaction (antibody-mediated). Smooth muscle and cardiac muscle are not usually affected by the disease.

AChR-Ab binding affects the NMJ is several ways:

- Blockage of ACh binding

- Cross linking of ACh-R, internalisation and destruction: global reduction in the number of ACh receptors able to contribute to muscular contraction, particularly on repeated use of the muscle

- Complement-mediated destruction of membrane: damage to post-synaptic membrane via the membrane attack complex (MAC). Limits the surface area available for insertion of new AChRs.

Once a certain threshold of receptors on the motor-end plate is lost, clinical symptoms of weakness are observed. The dynamic process of the condition with fluctuation in strength is largely owed to the ability of the NMJ to repair itself and form more ACh receptors without major difficulty.

As part of the physiology of the NMJ, several additional proteins are important in ACh binding and receptor activation. These include proteins MuSK and LRP. This highlights why antibodies generated against these proteins may also lead to the development of MG.

Classification and subtypes

There are different subtypes of MG, which impact on both treatment and prognosis.

There are multiple ways of classifying MG, which can be based on clinical features, antibodies, presence of thymic abnormality or age of onset.

Clinical subtypes

- Ocular MG: weakness limited to eyelids extraocular muscles. Only 50% seropositive.

- Generalised MG: can affect numerous muscle groups including neck, bulbar, limbs, respiratory and ocular. Up to 90% seropositive.

Antibody subtypes

- MG with AChR-Ab: 80-90% of cases

- MG with Anti-MuSK: ~4% of cases

- MG with Anti-LRP4: ~2% of cases

- Seronegative myasthenia

Thymic abnormalities

- Normal

- Thymoma: 10-15% of patients with MG

- Hyperplasia

- Atrophy

Age of onset

- Neonatal

- Juvenile

- Early-onset (< 50 years)

- Late-onset (≥ 50 years)

Seronegative myasthenia

Patients without detectable autoantibodies are said to have seronegative MG.

Traditionally, patients with MG who did not have AChR antibodies were classified as ‘seronegative’. Approximately, 50% of these patients have been identified to have another autoantibody known as muscle-specific receptor tyrosine kinase (MuSK). Other autoantibodies involved in the pathogenesis of MG has been identified including anti-lipoprotein receptor-related protein 4 (LRP4). Both MuSK and LRP4 are important in the normal function of the NMJ.

Now, patients without AChR, MuSK or LRP4 autoantibodies are classified as seronegative MG. Other autoantibodies have been associated with MG in both seropositive and seronegative cases (e.g. anti-striated muscle antibodies).

Clinical features

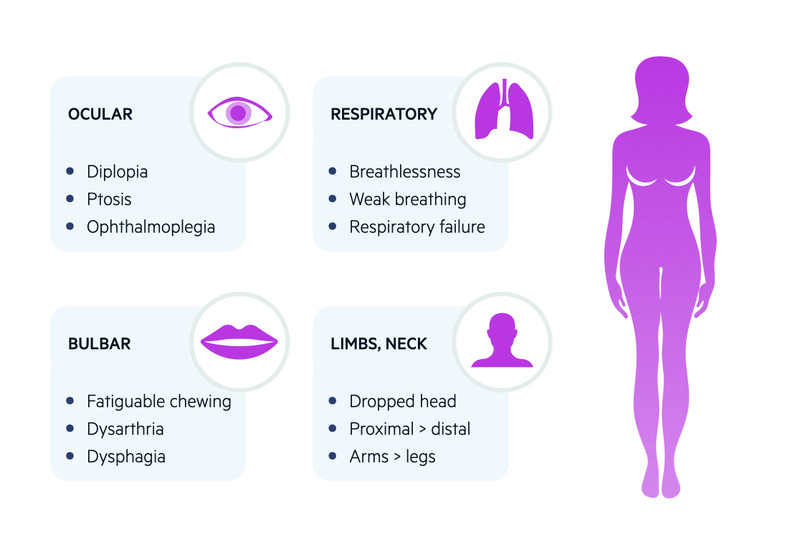

MG is broadly classified into two clinical forms: ocular and generalised.

The hallmark clinical feature of MG, in both ocular and generalised, is fluctuating skeletal muscle weakness. This usually presents with fatiguability that refers to increased muscle weakness on repeated use.

Symptoms are commonly worse at the end of the day or following exercise. As the condition progresses, there may be no periods of normal muscle function. Instead, weakness may merely fluctuate between mild and severe.

Ocular

More than 50% present with ocular symptoms

- Diplopia: double vision. Should improve on closing, or occluding, one eye.

- Ptosis: drooping of upper eyelid. May be asymmetrical and fluctuant. May be enhanced on prolonged upward gaze.

- Weak eye movements: unusual pattern of weakness that does not correlated to a single nerve or muscle (helping differentiate it from a cranial nerve palsy)

- Pupillary sparing: no evidence of abnormally small or large pupils and react to light.

Around 50% of patients with ocular myasthenia will develop generalised disease within two years of onset. Furthermore, up to 25% will only have ocular symptoms throughout their disease course.

Generalised

Approximately 15% present with bulbar symptoms and 5% with limb weakness alone

- Bulbar muscles: fatiguable chewing, dysarthria, dysphagia.

- Facial muscles: expressionless face. Poor smile or classical ‘myasthenic sneer’ (mid lip rises but outer mouth corners fail to move)

- Neck muscles: extensor and flexor muscles can be affected. May get ‘dropped-head syndrome’ towards end of day.

- Limb muscles: mainly proximal muscle weakness. Arms affected more than legs

- Respiratory muscles: most serious presentation. Can lead to respiratory failure, which is life-threatening. May present with myasthenic crisis (discussed below). May occur spontaneously or be precipitated*.

*NOTE: common precipitants of respiratory muscle weakness and subsequent myasthenic crisis include surgery, infections, medications or tapering immunosuppression.

Ice pack test

Refers to the improvement of ptosis in patients with MG after the application of a bag filled with ice to the closed eyelid for one minute. After removal, the extent of ptosis is immediately assessed. There should be a short duration of improvement (< 1 minute). Sensitivity is approximately 80%.

The test relies on the principle that neuromuscular transmission is better at lower muscle temperature. The ice pack test is not diagnostic and instead, supports the diagnosis when suspected.

Diagnosis & investigations

The diagnosis of MG is generally based on clinical features and serological testing.

Muscle weakness with fatiguability and the presence of AChR-Ab are usually enough to support the diagnosis of MG and consider treatment. All patients with suspected MG should be referred to a neurologist for further assessment and initiation of treatment. Patients with severe symptoms or concern about myasthenic crisis need urgent hospital admission.

Bedside

- Ice-pack test: discussed above

- Edrophonium (tensilon) test: no longer completed in clinical practice. Consisted of an infusion of edrophonium, which is an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor with rapid onset and short duration. Leads to a brief improvement in symptoms in patients with obvious ptosis or ophthalmoplegia. False positive and negatives. Safety concerns due to muscarinic side-effects (e.g. bradycardia, bronchospasm).

Serological

- AChR-Ab: 90% of generalised, 50% of ocular MG. High specificity (~99%). Rarely, may see false positives in a patient with thymoma without MG.

- MuSK and LRP4: completed if AChR-Abs are negative. Typical clinical phenotype.

- Others: multiple antibodies against differentiate components of skeletal muscle (Anti-striated muscle antibodies). Strongly linked with thymoma.

Neurophysiology

Repetitive nerve stimulation (RNS) and electromyography (EMG) can be used to help diagnose MG, especially in seronegative cases.

In RNS, an electrode is placed over a region of muscle and the motor nerve to that muscle is stimulated repeatedly at 2-3 Hz around 6-10 times. In MG, with repeated stimulation there is a progressive decline in amplitude suggesting fatiguability. EMG is more sensitive, but more technically difficult. May be used if RNS is negative or where availability allows.

Assessment of thymus gland

All patients with suspected MG, irrespective of clinical or serological subtype need to undergo assessment of the thymus gland using CT or MRI. Both imaging modalities are excellent at identification of a thymoma, but it may be difficult to distinguish between thymoma and hyperplasia. Thymoma is very uncommon in the absence of AChR-Ab or anti-striated muscle antibodies .

Others

All patients should undergo thyroid function tests because of the strong association with thyroid autoimmune disease. Other tests including a rheumatological screen (e.g. ANA, ENA, CCP, RF) or cerebral imaging (e.g. MRI brain) are guided by the clinical presentation and presence or absence of typical antibodies.

Management

The principle initial treatment for MG is pyridostigmine, which is an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor.

There are numerous treatment options for MG, which depend on the clinical subtype (ocular versus generalised), whether symptoms respond to therapy and whether they have, or are at risk of, myasthenic crisis.

Treatment options

- Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (e.g. pyridostigmine): prevent the hydrolysis of acetylcholine and increases its effect at the NMJ. Usually given as initial therapy. Associated with cholinergic side-effects (secretions, diarrhoea, GI upset, bronchospasm, sweating, urinary incontinence).

- Corticosteroids (e.g. prednisolone): immunosuppressive effects. Given if ongoing symptoms despite pyridostigmine. Given as an alternate day strategy and dose increased until symptomatic improvement. Different dose if ocular or generalised.

- Immunosuppressants: Azathioprine usually offered first-line. Inhibits purine synthesis. Must check TPMT level before use due to risk of bone marrow suppression. Other options include mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, ciclosporin, rituximab (anti-CD 20 monoclonal antibody)

Ocular myasthenia

- Initial therapy: pyridostigmine (usually 15 mg QDS for 2-4 days then slowly uptitrate according to protocol).

- If failing to respond: introduce prednisolone at 5 mg alternate days and then increase as per protocol (max 50 mg alternate days). Consider bone and gastric protection as likely long-term use. Counsel on side-effects.

- Resistant symptoms, high steroid dose or side-effects: consider immunosuppressant therapy with azathioprine or other agent if contraindication.

- Relapses: identify a precipitant, consider restarting or escalating corticosteroids. May need to consider starting or altering immunosuppressant.

Generalised myasthenia

- Initial therapy: pyridostigmine (usually 15 mg QDS for 2-4 days then slowly uptitrate according to protocol).

- If failing to respond: introduce prednisolone at 10 mg alternate days and then increase as per protocol (max 100 mg alternate days). Consider bone and gastric protection as likely long-term use. Counsel on side-effects.

- Resistant symptoms, high steroid dose or side-effects: consider immunosuppressant therapy with azathioprine or other agent if contraindication.

- Relapses: identify a precipitant, consider restarting or escalating corticosteroids. May need to consider starting or altering immunosuppressant.

Thymectomy

Patients with evidence of a thymoma should be referred to a thoracic surgeon for consideration of thymectomy. This is usually completed in a centre with access to neurology input and specialist anaesthetic care due to the risk of deterioration peri-procedure. Thymectomy can also be considered in patients without thymoma who are < 45 years old and have positive AChR antibodies.

Myasthenic crisis

Myasthenic crisis is a life-threatening condition.

A myasthenia crisis is defined as a worsening of weakness that requires respiratory support (e.g. intubation or non-invasive ventilation). Up to 20% of patients will experience a MG crisis within their lifetime.

It is important to recognise patients with, or at risk of, a myasthenic crisis because they need urgent admission to hospital and possible referral to the high-dependency unit (HDU) or intensive treatment unit (ITU).

Inpatient management

Inpatient management should be considered in any patient with, or at risk of, a myasthenic crisis. This includes those with:

- Significant bulbar symptoms

- Low forced vital capacity (FVC)

- Respiratory symptoms

- Progressive deterioration

All inpatients should be assessed by the speech and language team (SALT) and should have regular assessment of their FVC. FVC is main tool for monitoring deterioration in respiratory function. If there are any concerns, patients should be referred to HDU/ITU where they can have closer monitoring of respiratory function and earlier intervention with respiratory support as needed.

Forced vital capacity

Measuring FVC should be based on weight and any significant fall should warrant referral to HDU/ITU for closer monitoring, or if significantly low, respiratory support.

Generally, an FVC < 30 ml/kg should warrant referral to HDU/ITU

- If weight 55 kg: FVC < 1.6L should warrant referral

- If weight 90 kg: FVC < 2.7L should warrant referral

If the FVC falls below 15-20 mls/kg, then elective intubation should be considered.

Pharmacological therapy

Patients with, or at risk of, a myasthenic crisis can be treated with urgent intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), corticosteroids and consideration of plasma exchange (removal and replacement of a patients blood plasma) if symptoms don’t respond.

- IVIG: consider if severe respiratory or bulbar symptoms (1-2 g/kg total dose, given over several days). May be repeated if limited initial effect, should be discussed with neurology.

- Plasma exchange: considered if poor response to IVIG. Removal of patients plasma and replaced with albumin or fresh frozen plasma.

- Corticosteroids: prednisolone can be reinstated via NG tube or orally depending on whether intubated. In general, if ventilated, give high dose (e.g. 100 mg alternate days). If not ventilated, can consider standard starting prednisolone protocol. May lead to a temporary worsening of symptoms within 5-10 days of starting treatment (less concern if also receiving IVIG).

Pyridostigmine should generally be avoided during an acute crisis due to the increase in respiratory secretions and risk of aspiration. Furthermore, excessive use of magnesium sulphate on ITU should be avoided where possible (precipitates worsening symptoms)

Precipitants

Several factors including medications, surgery or intercurrent illness are well recognised to precipitant symptoms.

Precipitating factors

- Warm weather

- Surgery

- Stress

- Infections and intercurrent illness

- Co-morbidities

- Pregnancy

- Medications

Medications

A number of medications have been recognised to worsen symptoms and may precipitate a myasthenic crisis. It is imperative to try and avoid these medications, where possible, in patients with MG.

- Antibiotics: aminoglycosides (e.g. gentamicin), ciprofloxacin, clindamycin, erythromycin

- Antihypertensives/Antiarrhythmics: beta-blockers, calcium-channel blockers

- Neuromuscular blocking agents: atracurium, vecuronium

- Many others (e.g. phenytoin, statins, lithium, penicillamine chloroquine, magnesium, prednisolone)

Prognosis

With modern treatment mortality from MG is 3-4%.

MG used to be associated with a high mortality (~40%). Morbidity is largely related to respiratory and bulbar muscle symptoms that may be associated with respiratory failure and aspiration.

Early in the disease, patients usually have fluctuant muscle weakness with long periods (hours/days/week) being symptom free. As the disease progresses, symptoms may worsen and become more persistent. The clinical manifestations generally peak within three years of onset.

Informally, there are three main stages of MG:

- Stage one (active): fluctuating muscle weakness with most severe clinical features. Majority of crises occur in this phase.

- Stage two (stable): persistent, but stable symptoms. Serious exacerbations may develop due to infection, medications, or altering treatment.

- Stage three (remission): a minority of patients may develop complete remission without need for treatment.

Last updated: October 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback