Mononeuropathies

Notes

Overview

A mononeuropathy refers to damage or dysfunction of a single peripheral nerve.

Mononeuropathy is a broad term that refers to damage or dysfunction of a single peripheral nerve. This typically leads to a characteristic set of clinical features with motor and/or sensory dysfunction relating to the usual function of the nerve involved.

Mononeuropathies are commonly due to entrapment or compression as peripheral nerves have to travels through small openings and between other major structures (e.g. median nerve compression within the carpal tunnel). This compression may be internal (e.g. nerve tumour), or external (e.g. fracture, compressive clothing, unusual posture). Management of mononeuropathies depends on the nerve involved and the underlying aetiology. For example, compression of the median nerve as it runs through the carpal tunnel may be treated by surgical release.

Here, we discuss some of the commonly observed upper and lower limb mononeuropathies.

Distribution

Mononeuropathies are commonly seen in the upper and lower limbs.

The peripheral nervous system sends and receives information from the brain and spinal cord that make up the central nervous system. The peripheral nervous system is divided into visceral and somatic fibres:

- Visceral fibres: divided into visceral sensory fibres that predominantly carry information from thoracic and abdominal compartments and visceral motor fibres that form the autonomic nervous system (ANS). The ANS is further divided into the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems

- Somatic fibres: these carry important sensory information from skin, muscles, bone and joints and motor information to glands and muscles

The motor and sensory somatic fibres are carried via the spinal nerves and cranial nerves. These nerves exit the brainstem and spine at different levels. When spinal nerves exit the spinal cord they may enter a plexus. A plexus simply refers to a branching network of nerves (or vessels). Eventually, these give rise to individual peripheral nerves (e.g. median, ulnar).

Mononeuropathies commonly affect cranial nerves and individual peripheral nerves of the upper and lower limbs. Therefore, we can broadly think of mononeuropathies in three groups:

- Cranial mononeuropathies: relates to the 12 paired nerves arising from the brain and brainstem

- Upper limb mononeuropathies: relates to the peripheral nerves involved in upper limb function

- Lower limb mononeuropathies: relates to the peripheral nerves involved in lower limb function

Upper limb

The major peripheral nerves of the upper limb arise from the brachial plexus. They provide both sensory and motor function. There are many upper limb nerves including:

- Median

- Ulnar

- Radial

- Axillary

- Other (e.g. musculocutaneous, long thoracic, suprascapular, spinal accessory)

Lower limb

The major peripheral nerves of the lower limb arise from the lumbosacral plexus. They provide both sensory and motor function. There are many lower limbs nerves including:

- Common peroneal

- Tibial

- Femoral

- Sciatic

- Other (e.g. sural, obturator, lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh)

Cranial nerves

Cranial nerve neuropathies may occur in isolation or in combination depending on the underlying aetiology and which part of the nerve is affected (e.g. cell body or axon). For example, diabetes mellitus may cause an isolated sixth cranial nerve neuropathy whereas a cavernous sinus thrombosis may affect the third, fourth, five and sixth nerves in combination.

In this note, we focus on mononeuropathies affecting the upper and lower limbs. For information on mononeuropathies affecting the cranial nerves check out the following notes:

Aetiology & pathophysiology

A single peripheral nerve injury is commonly due to compression.

Peripheral nerves may be damaged from a variety of insults. However, damage or dysfunction of a single peripheral nerve commonly occurs secondary to a compressive aetiology. Other factors include transection, inflammation, ischaemia, or even radiation.

Compression

Compression of peripheral nerves is common as they travel along their course. Examples include:

- Entrapped in a ligamentous canal

- Entrapped within a facial compartment

- Local compression by a tumour

It is a combination of nerve compression and ischaemia that leads to damage and neurological symptoms. Compression may occur acutely (e.g. compartment syndrome) or occur chronically (e.g. carpal tunnel syndrome).

In mild cases, compression may occur when the limb is held in a certain position leading to temporary paraesthesia from ischaemia of the nerve. For example, leaning on the elbow leads to compression of the ulnar nerve. If compression becomes more consistent or chronic there is demyelination with additional pain and weakness. Over time, the distal segment of the nerve stops functioning and there is Wallerian degeneration that essentially refers to axonal damage distal to the problem. Functional loss of sensation and strength is seen when there is a complete conduction block in the nerve.

Transection

This refers to the complete separation of a nerve. It is commonly the result of trauma (e.g. knife injury). Without urgent reattachment, regrowth of the nerve is impossible.

Ischaemia

Damage to the blood vessels that supply peripheral nerves known as the vasa nervorum can lead to infarction and neuropathy, usually from axonal injury. This can be due to vasculitis, atherosclerotic disease, or other conditions such as diabetes mellitus.

Others

A variety of other aetiologies can lead to single nerve damage including infections (e.g. varicella zoster virus), inflammation, radiation, or metabolic processes (e.g. hypothyroidism).

Median neuropathy

Carpal tunnel syndrome is the most common cause of a median nerve neuropathy.

The median nerve is derived from the lateral and medial cords of the brachial plexus (C5-T1). It enters the upper arm at the axilla and travels alongside the brachial artery into the cubital fossa. It then travels in the anterior forearm before passing through the carpal tunnel to supply some intrinsic muscles of the hand.

Sensory function

The median nerve provides sensory innervation to the hand. This includes the palmar and distal dorsal aspects of the lateral three-and-a-half digits (thumb, index, middle, and half of the ring finger) and central palm. The sensation of the palm is provided by the median nerve and a small sensory branch known as the palmar cutaneous, which branches before the carpal tunnel.

Motor function

In the forearm, the median nerve provides innervation for:

- Pronator teres

- Flexor carpi radialis

- Palmaris longus

- Flexor digitorum superficialis

A branch of the median nerve known as the anterior interosseous arises within the forearm and provides innervation for:

- Pronator quadratus

- Flexor pollicis longus

- Part of the flexor digitorum profundus

The median nerve enters the wrist through the carpal tunnel with nine flexor tendons. It goes on to provide motor innervation to the thenar eminence and two lateral lumbricals that can be remembered as ‘2LOAF’.

Aetiology

There are several causes of median nerve neuropathy but the most common is carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS). CTS is due to compression of the median nerve as it passes through the carpal tunnel formed by the flexor retinaculum superiorly and carpal bones inferiorly. It is the most common upper limb mononeuropathy that may be due to structural compression or inflammation. Risk factors include diabetes mellitus, pregnancy, rheumatoid arthritis, obesity and thyroid disease.

Other causes of median nerve neuropathy are due to compression anywhere along its course (e.g. by haematoma, trauma or tumour) or from non-compressive aetiologies such as diabetes mellitus or vasculitis. Two characteristic syndromes related to compression of the median nerve and/or its branches are pronator teres syndrome and anterior interosseus nerve syndrome.

- Pronator teres syndrome: compression of the median nerve in the forearm as it passes through the pronator teres. A rare syndrome typically seen in physically active people (e.g. professional cyclists).

- Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome: compression of the isolated motor branch of the median nerve known as the anterior interosseous. Although this syndrome is rare, it has a very classic clinical examination finding of being unable to make the ‘okay’ sign.

Clinical features

The clinical features of median nerve neuropathy can vary depending on the underlying cause or level of compression/entrapment. Characteristic features include:

- Sensory loss and/or paresthesia: typically seen over the palmar and distal dorsal aspects of the thumb, index, middle and half of the ring finger.

- Weakness or clumsiness using the hand

- Weak thumb abduction

- Thenar eminence wasting

- Hand pain: typically worse at night (carpal tunnel syndrome)

In the setting of carpal tunnel syndrome a few provocative manoeuvres can be performed, which are tests designed to elicit symptoms on examination. These include Phalen and Tinel.

- Phalen manoeuvre: ask the patient to hyperflex both hands and hold dorsal surfaces together. This should be held for 1 minute. A positive test leads to pain and/or paraesthesia in the distribution of the median nerve

- Tinel test: percuss over the median nerve just proximal to the carpal tunnel. A positive test leads to pain and/or paraesthesia in the distribution of the median nerve

NOTE: Tinel's test is a non-specific test to assess for peripheral nerve injury by tapping proximal to the damaged nerve. Commonly used in Carpal tunnel syndrome, but may be used in other peripheral nerve injuries (e.g. tarsal tunnel syndrome)

Ulnar neuropathy

The ulnar nerve may become trapped at the elbow or the wrist.

The ulnar nerve is a continuation of the medial cord of the brachial plexus (C8-T1). The ulnar nerve lies medial to the brachial artery in the upper arm. At the elbow, the ulnar nerve passes between the medial epicondyle of the humerus and olecranon of the ulna. Posterior to the medial epicondyle the ulnar nerve is easily palpable.

The ulnar nerve subsequently runs through two main tunnels that can lead to compression:

- Cubital tunnel at the elbow: bordered by the medial epicondyle, olecranon and arcuate ligament (connects two heads of flexor carpi ulnaris)

- Guyon’s (ulna) canal at the wrist: a groove between the pisiform carpal bone and the hook of hamate that are joined by the palmar carpal ligament

Sensory function

The ulnar nerve provides sensory function to the skin of both the palmar and dorsal aspects of the medial one-and-a-half digits and adjacent palm. In other words, the little finger and medial side of the ring finger. It also provides sensation to the medial side of the dorsum of the hand.

Motor function

The ulnar nerve provides motor innervation to some muscles in the forearm:

- Flexor carpi ulnaris

- Flexor digitorum profundus (medial half)

The ulnar nerve also provides motor innervation to all the intrinsic muscles of the hand except the ‘LOAF’ muscles supplied by the median nerve as discussed in median neuropathy.

- Hypothenar muscles: Opponens digiti minimi, abductor digiti minimi, flexor digiti minimi brevis

- Interossei muscles

- Medial two lumbricals

- Flexor pollicis brevis

- Adductor pollicis

Aetiology

Ulnar neuropathy is often due to compression at the elbow or wrist. Compression can occur anywhere along its course due to haematoma, trauma or tumour for example. Non-compressive aetiologies can include diabetes mellitus or vasculitis.

At the elbow, the ulnar nerve is particularly vulnerable to compression around where it passes through the cubital tunnel. The broad term 'ulnar compression at the elbow' is used to reflect that the nerve can be compressed anywhere along its course in the region and not just within the cubital tunnel. Compression just in this tunnel may be termed cubital tunnel syndrome. Compression may occur due to trauma (e.g. distal humerus fracture), prolonged elbow flexion, leaning on the elbow, osteophyte formation due to arthritis, or other mass lesions.

At the wrist, the ulnar nerve is commonly compressed as it passes through Guyon's canal due to trauma, direct pressure (e.g. leaning on the handlebars of a bike) or prolonged use of hand tools.

Clinical features

Ulnar neuropathy typically presents with sensory changes in the distribution of the ulnar nerve with hand weakness due to loss of intrinsic muscle function. Ulnar neuropathy is characterised by:

- Sensory loss and/or paraesthesia: seen over the little finger and medial side of the ring finger

- Hand weakness (loss of dexterity, grip weakness)

- Muscle wasting: seen over the hypothenar eminence and/or interossei muscles

- Claw hand deformity (if severe): usually more pronounced with compression of the wrist

Long-standing ulnar neuropathy may lead to deformity in the hand known as a 'claw hand'. This refers to hyperextension of the 4th and 5th metacarpophalangeal joints with flexion at the interphalangeal joints. This is particularly noticeable when opening the hand and is due to loss of medial lumbrical function.

Hand deformities can actually be very confusing in the medical literature. There are lots of terms such as 'Ape hand', ‘Hand of benediction’ and ‘Claw hand’.

- Ape hand: failure of thumb opposition and abduction (due to median nerve neuropathy)

- Hand of benediction: has been attributed to both ulnar and median nerve neuropathies

- Ulnar: seen when trying to open the hand. Hyperextension at 4th/5th MCP joints with abnormal flexion in the IP joints

- Median: seen when trying to close the hand. Abnormal flexion of the 2nd/3rd fingers

Therefore, the typical appearance of the hand of benediction may be seen in both ulnar and median neuropathy. It is differentiated based on the movement that promotes the deformity (i.e. opening or closing the hand) and the associated sensory loss (i.e. sensory changes in the distribution of the median or ulnar nerve). The 'ulnar claw' or simply 'claw hand' is another term for the hand of benediction secondary to an ulnar neuropathy.

Test of ulnar function

There are two important clinical signs to test for ulnar nerve function:

- Froment’s: ask the patient to pinch a piece of paper between thumb and index finger. As the examiner pulls the paper away, if there is flexion of the distal phalanx of the thumb this suggests ulnar weakness. This is because flexion of the distal phalanx of the thumb is performed by the median-nerve inverted flexor pollicis longus

- Wartenberg’s: ask the patient to hold the fingers fully extended and close together (i.e. adducted). If the little finger drifts away this is positive. Due to weakness of the ulnar-nerve innervated third palmar interosseous muscle. Alternatively, ask the patient to pinch a piece of paper between the little finger and ring finger. The examiner should then attempt to pull the piece of paper away

Radial neuropathy

The classic presentation of radial neuropathy is acute ‘wrist drop’.

The radial nerve is a continuation of the posterior cord of the brachial plexus (C5-T1). Around the mid-humerus is a shallow depression known as the radial groove or spiral groove that the nerve runs along. As the nerve reaches the elbow is wraps around the humerus and passes anteriorly to the lateral epicondyle and through the cubital fossa to give off two terminal branches: superficial sensory branch and deep motor branch.

Sensory function

The radial nerve provides sensory innervation for the dorsal aspect of the radial (i.e. lateral) three-and-a-half digits of the hand (i.e. thumb, index, middle, and lateral half of ring finger). Within the arms and forearm, sensory branches are given off that provide innervation for the skin on the posterior and outer surface of the arm and forearm.

Motor function

The radial nerve has important function for several muscles in the arm:

- Triceps brachii

- Extensor carpi radialis longus

- Brachioradialis

- Anconeus

As the nerve passes through the cubital tunnel into the forearm it continues as the posterior interosseous nerve that provides innervation to the extensor muscles of the forearm:

- Extensor carpi radialis brevis

- Supinator

- Abductor pollicis longus

- Extensor carpi ulnaris

- Extensor digiti minimi

- Extensor digitorum

- Extensor indicis

- Extensor pollicis brevis

- Extensor pollicis longus

Aetiology

The radial nerve is particularly vulnerable to compression as it wraps around the posterior surface of the mid-humerus along the radial groove also known as the spiral groove. Classic causes of neuropathy here include a mid-humeral fracture or Saturday night palsy. The key presenting feature in radial neuropathy is ‘wrist drop’ due to weakness of the forearm extensor muscles.

Saturday night palsy is a classic presentation commonly seen in patients who are heavily inebriated and place their arm over a chair (or another object) for an extended period of time leading to a pressure injury of the radial nerve.Other causes of radial neuropathy can occur due to compression at other locations along the nerves course (e.g. haematoma, trauma, tumour) or from non-compressive aetiologies such as diabetes mellitus or vasculitis.

Another classic syndrome is known as posterior interosseous syndrome due to compression of the posterior interosseous branch of the radial nerve. This is commonly due to trauma, repetitive pronation/supination activities or space-occupying lesions.

Clinical features

The hallmark of radial nerve neuropathy is wrist drop that occurs alongside weak finger extension. Characteristic features include:

- Sensory loss and/or paraesthesia over the dorsum of the hand (may extend up posterior aspect of the forearm)

- Wrist drop

- Weakness in finger extension

- Weakness in brachioradialis (best assessed by testing forearm flexion against resistance with the forearm in a ‘banging the table’ position)

NOTE: isolated neuropathy of the posterior interosseous nerve classically causes weak finger extension with sparing of the proximal muscle groups and no sensory changes (it is a primary motor nerve).

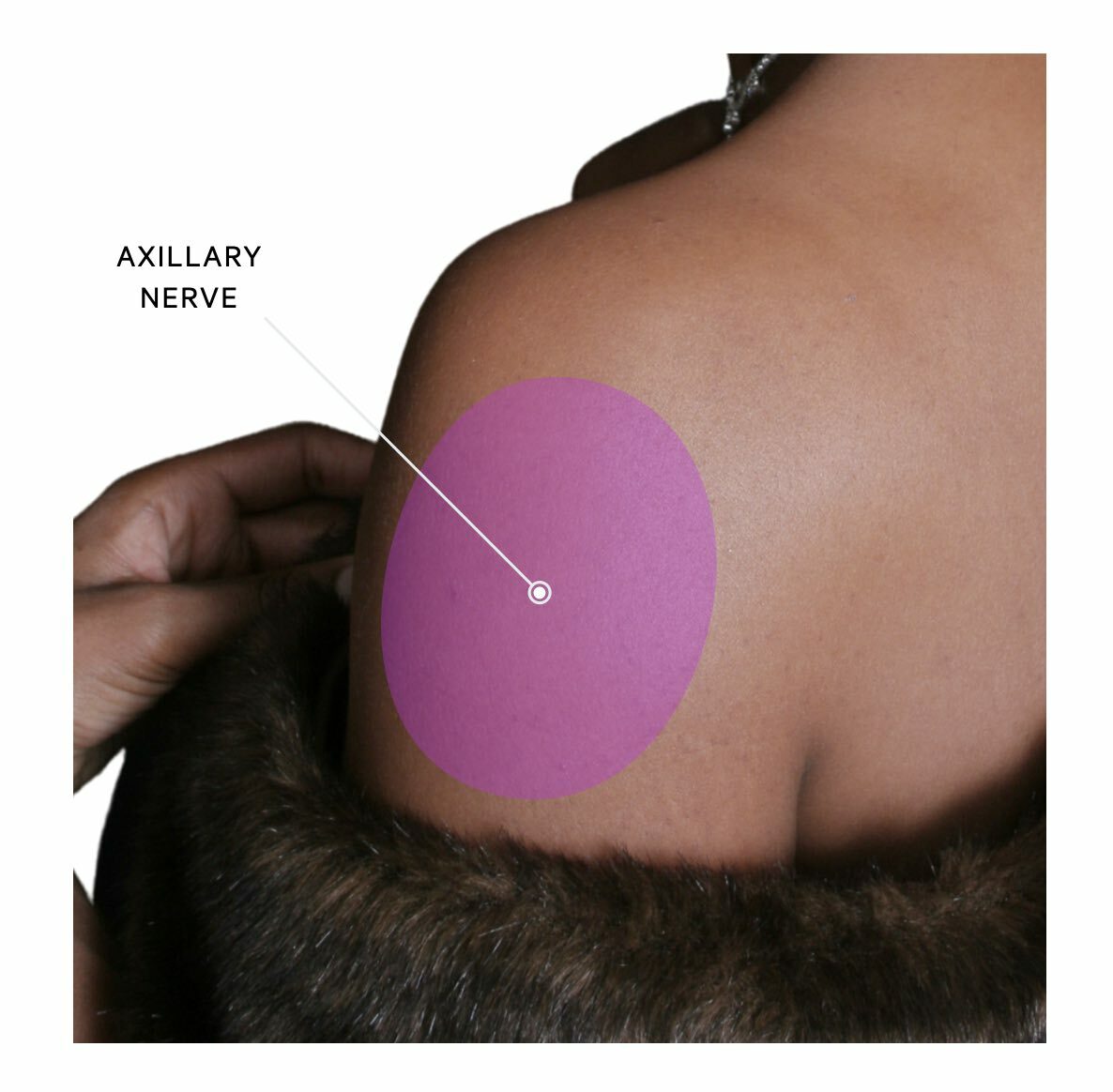

Axillary neuropathy

An axillary neuropathy is most commonly due to trauma such as shoulder dislocation.

The axillary nerve is a branch of the posterior cord of the brachial plexus (C5-6). It has both sensory and motor function in the upper arm including important shoulder muscles.

Sensory function

The axillary nerve supplies a small oval-shaped patch of cutaneous skin on the lateral aspect of the shoulder. This is often known as the ‘regimental badge area’. It also carries sensory information from the glenohumeral joint (i.e. the shoulder joint).

Motor function

The axillary nerve has important motor functions to several muscles involved in shoulder movement. These include:

- Deltoid

- Teres minor

- Lateral head of the triceps brachii

Aetiology

The most common cause of axillary neuropathy is trauma. This may be from shoulder dislocation or proximal humeral fracture.

Clinical features

Axillary neuropathy is characterised by a sharp sensory loss over the lateral shoulder. Weakness may be present but it is usually highly variable due to many other muscles contributing to shoulder movement. Pain is typically a predominant feature due to the aetiology of trauma/dislocation and this may be present with shoulder deformity.

Common peroneal neuropathy

The classic presentation of a common peroneal neuropathy is acute ‘foot drop’.

The common peroneal nerve is a terminal branch of the sciatic nerve that arises from L4-S2. It is also known as the common fibular nerve. The nerve arises from the sciatic nerve in the deep posterior thigh and then passes through the popliteal fossa. It then passes around the head of the fibula, which is a common site of compression leading to neuropathy.

After curving around the head of the fibula it divides into the superficial and deep peroneal nerves.

Superficial peroneal nevre

The superficial peroneal nerve has both sensory and motor function.

- Sensory: skin over the anterolateral aspect of the lower limb and dorsum of the foot

- Motor: muscles in the lateral compartment of the leg (fibularis longus and fibularis brevis)

Deep peroneal nerve

The deep peroneal nerve also has sensory and motor functions.

- Sensory: first dorsal webspace (i.e. between the big and second toe)

- Motor: muscles in the anterior compartment of the leg (Tibialis anterior, extensor hallucis longus, extensor digitorum longus)

Aetiology

Common peroneal neuropathy is commonly due to trauma/injury to the knee (e.g. proximal fibular fracture, knee dislocation) or from external compression such as a tight splint or cast, habitual leg crossing, or even abnormal positioning during general anaesthesia. Non-compressive causes are variable and may include diabetes mellitus or vasculitis.

Clinical features

A common peroneal neuropathy is characterised by ‘foot drop’ due to weakness of dorsiflexion at the ankle that may lead to the patient ‘catching their toe’ or ‘tripping’ when walking. There is usually sensory loss or paraesthesia over the dorsum of the foot and lateral shin. On examination, there is weak dorsiflexion and eversion of the ankle.

Tibial neuropathy

The tibial nerve is most commonly compressed as it passes under the transverse tarsal ligament in the ankle.

The tibial nerve is one of the terminal branches of the sciatic nerve that arises from L4-S3. The tibial nerve runs within the posterior compartment of the lower leg. It exits the posterior compartment and enters the sole of the foot through the tarsal tunnel, which lies posterior to the medial malleolus.

Sensory function

The tibial nerve has several sensory branches that supply the skin of the posterolateral lower leg, lateral foot, and sole of the foot. One of these branches is known as the sural nerve that provides innervation to the posterolateral lower leg. This is important because the nerve may be affected in isolation.

Motor function

The tibial nerve has important motor function to muscles within the posterior compartment of the foot and the intrinsic muscles of the foot.

Aetiology

The most common cause of tibial neuropathy is compression as it passes under the transverse tarsal ligament in the ankle, which is known as tarsal tunnel syndrome. The most common cause of this is a fracture and/or dislocation of the ankle, whereas other causes can include inflammatory arthritis or tumours.

More proximal compression of the tibial nerve is uncommon due to its deep location within the posterior compartment of the leg but can occur with problems within the popliteal fossa such as a large Baker’s cyst.

Clinical features

Tibial nerve neuropathy is characterised by paraesthesia, pain, and numbness over the sole of the foot, which may be worse at night or prolonged standing. Tinel’s test may be positive, which refers to pain or tingling over the distribution of the nerve when tapping repeatedly on the tarsal tunnel. In long-standing cases, there may be atrophy of the intrinsic muscles of the foot.

Various foot deformities may be seen due to weakness of the intrinsic foot muscles including:

- Pes planus

- Pronated foot

- Abnormal gait (e.g. antalgic gait, excessive pronation)

Meralgia paraesthetica

Meralgia paraesthetica refers to pain and/or sensory loss over the anterolateral thigh.

Meralgia paraesthetica is due to neuropathy of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve which is a small sensory nerve supplying cutaneous tissue over the anterolateral portion of the thigh. The nerve branches from the lumbar plexus roots L2/L3 and runs lateral to the psoas muscle and then passes underneath the inguinal ligament.

Neuropathy commonly occurs due to entrapment at it passes under the inguinal ligament. Major risk factors for the condition include diabetes mellitus, obesity, and older age.

The condition is characterised by pain, paraesthesia, and numbness over the anterolateral aspect of the thigh. There is usually reduced pin-prick sensation on clinical testing and motor signs should be absent (it is solely a sensory nerve). More than 90% of patients respond to conservative treatment (e.g. weight loss, alter clothing choice that compresses the nerve around the waist).

Diagnosis & investigations

The diagnosis of mononeuropathies is confirmed on electrodiagnostic testing.

Mononeuropathies are most commonly due to focal entrapment or compression. Therefore, the predominant investigations are electrodiagnostic tests to confirm the neuropathy (i.e. abnormal conduction through the nerve) and imaging to identify the cause of the compression. Specific blood tests should be requested depending on the suspected cause (e.g. thyroid function and diabetes mellitus in carpal tunnel syndrome). When a systemic syndrome is suspected (e.g. vasculitis) then more extensive blood tests are usually required.

Electrodiagnostic tests

Electrodiagnostic tests including nerve conduction studies and electromyography are the best way of diagnosing and characterising mononeuropathies.

- EMG (evaluates muscle units): this refers to an assessment of the electrical activity of muscles. It can assess activity during rest and voluntary contraction. Records the electrical potentials generated in a muscle belly through the insertion of a needle

- NCS (evaluates peripheral nerves): this refers to an assessment of individual peripheral nerve function. It essentially involves activating nerves electrically over several points on the skin of the upper/lower limbs and measuring the response. The test involves assessing both the size (i.e. amplitude) and speed (i.e. velocity) of signals through motor and sensory fibres

Electrodiagnostic tests usually enable localisation of the suspected entrapment by looking for demyelination over the affected segment of the nerve. They can also be very useful at differentiating between mononeuropathies, plexopathies, and radiculopathies.

Imaging

Imaging is useful in the workup of mononeuropathies, which is usually due to compression. Patients presenting with acute mononeuropathies secondary to injury or trauma may undergo X-rays or computed tomography (e.g. fractured humerus). In patients with chronic mononeuropathies, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is usually the principal investigation. It is often completed following electrodiagnostic studies to help target the scan to the correct location. Imaging is essential to exclude mass lesions such as tumours.

Management

The management of a mononeuropathy depends on the type of neuropathy and underlying cause.

There are both non-surgical and surgical options for the management of mononeuropathies. This largely depends on the type, severity and cause of the underlying neuropathy. For example, carpal tunnel syndrome may be treated with wrist splints, corticosteroid injection, or surgical decompression. In another example, a common peroneal neuropathy may be managed by removing the external compression and providing an orthosis to keep the foot in dorsiflexion alongside physiotherapy.

Individual management of mononeuropathies is beyond the scope of this note.

Last updated: July 2022

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback