Paracetamol overdose

Notes

Overview

Paracetamol poisoning is the most common overdose seen in the UK.

Paracetamol is a commonly used anti-pyretic and analgesic that can be purchased 'over the counter'. It has an excellent safety profile and is used for a variety of conditions. However, in overdose, it can lead to drug-induced liver injury (DILI). Within the UK, paracetamol overdose is the most common cause of acute liver failure (ALF) requiring liver transplantation.

Paracetamol overdose is frequently seen in the emergency department and most hospitals will have a local policy for its management. These policies will be based on advice from the national poisons information service (NPIS), which provides a clinical toxicology database known as ‘Toxbase’ (login required). This provides information on the diagnosis, treatment and management of patients who have been exposed to a wide range of medications, chemicals, plants and animals.

Risk assessment

Risk assessment is based on amount of paracetamol ingested (mg/kg) and time since ingestion.

All patients presenting known to have taken an overdose of paracetamol should have the following risk assessment as a minimum:

- Date of ingestion: is there a delay in presentation?

- Timing of ingestion: single overdose or staggered

- Time since last ingestion (even staggered)

- Weight: if >110 kg, used 110 kg as the maximum weight for calculations.

- Pregnancy: use pre-pregnancy weight to determine toxicity and current weight for treatment

- Total amount ingested (mg/kg)

- Current suicidal risk: consider a registered mental health nurse (RMN) to stay with the patient

Doses < 75 mg/kg are unlikely to cause toxicity unless staggered. Doses > 150 mg/kg are associated with serious or fatal adverse effects from toxicity and total doses > 12 g are potentially fatal.

Paracetamol ingestion

It is essential to understand and characterise the type of paracetamol ingestion as it determines management.

Acute ingestion

This refers to the ingestion of a potentially toxic dose of paracetamol within one hour or less.

Serious toxicity is unlikely if a patient has ingested <75 mg/kg. If a patient has ingested > 75 mg/kg, are symptomatic, or need urgent psychiatric assessment (if taken in context of self-harm), hospital admission is warranted.

Staggered ingestion

This refers to excessive ingestion of paracetamol over a period longer than one hour, usually in the context of self-harm.

Serious toxicity may occur in patients who have ingested > 150 mg/kg in any 24 hour period. Rarely, toxicity may occur for ingestions between 75-150 mg/kg. Doses consistently < 75 mg/kg in any 24 hour period are unlikely to be toxic. However, if paracetamol above the recommended daily dose (4g/24 hours in adults) is ingested for the two preceding days or more, the risk increases.

All patients that have taken a staggered overdose should be referred to hospital for assessment.

Unknown time of ingestion

If the time of ingestion is unknown patients should be treated as a ‘staggered overdose’.

Delayed presentation

This refers to a delay between the time of overdose and presentation to medical care.

This may be in the context of an acute overdose or staggered overdose. If a significant delay is suspected, treatment is usually initiated first whilst awaiting further investigations.

Unintentional

This refers to the unintentional use of excess paracetamol with the intent to treat an underlying problem (e.g. pain, fever) without intention of self-harm.

Patients should have ingested paracetamol at a dose greater than the licensed daily dose (4g/24 hours) and ≥75 mg/kg over 24 hours. Patients may have inadvertently taken paracetamol in addition to a paracetamol containing product (e.g. co-codamol). If there is uncertainty whether the presentation is unintentional therapeutic excess, patients should be managed as a staggered overdose.

Pathophysiology

Paracetamol is primarily metabolised in the liver to non-toxic metabolites, in overdose these pathways become overwhelmed.

Once ingested, paracetamol reaches peak concentration at 4 hours with an average half life of 2 hours. This may be significantly increased in the presence of hepatic dysfunction.

Paracetamol is primarily metabolised in the liver. This occurs via conjugation with the addition of glucuronide to form a water soluble metabolite that can be excreted in the urine. When there is excess paracetamol, such as with overdose, conjugation become saturated and paracetamol is converted into the metabolite N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine (NAPQI).

NAPQI has a short half-life and is usually conjugated by the addition of glutathione, which is then renally excreted. When glutathione stores are depleted, excess NAPQI binds to hepatocellular proteins and results in oxidative damage, mitochondrial dysfunction and ultimately hepatocellular injury. Anything that effects glutathione reserves may increase the risk of severe hepatotoxicity such as fasting, excess alcohol consumption and certain drugs.

Natural history

Patients may be completely asymptomatic in the early stages following overdose. Common symptoms include nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain.

Rarely, patients who have taken a significant overdose with very high plasma paracetamol concentrations may develop early metabolic acidosis, raised lactate and possibly coma. This is a separate clinical syndrome to the development of ALF, which is a direct drug effect of paracetamol on the functioning of mitochondria, which usually resolves with falling paracetamol levels.

Around 12-36 hours following overdose patients may experience abdominal pain. At 48-72 hours, patients may develop clinical features due to hepatic necrosis, which include right upper quadrant pain, nausea, vomiting, jaundice, acute kidney injury (i.e. oligo-/anuria) and hepatic encephalopathy (HE). The development of HE with coagulopathy (INR >1.5) is indicative of ALF and patients require urgent transfer to a transplant unit for further assessment.

Some patient may require urgent liver transplantation whereas others may show spontaneous recovery but need supportive care in intensive care during this process. Clinical recovery can take up to 3 weeks and complete hepatic recovery seen on histology can take several months.

Clinical features

Patients may be asymptomatic in the early stages of paracetamol overdose.

Many patients may be asymptomatic and show spontaneous recovery without a major effect on liver function. Others, particularly with significant overdoses, may have a wide range of clinical features due to severe hepatocellular injury.

Symptoms

- Nausea & vomiting

- Anorexia

- Malaise

- Abdominal pain

- Altered mental status

- Confusion

- Scars: evidence of previous self-harm

Signs

- Asterixis

- Bruising

- Jaundice

- Right upper quadrant pain

- Oliguria/anuria

- Tachycardia/hypotension

- Coma

Diagnosis and investigations

Diagnosis of paracetamol overdose is based on the history, but investigations are needed to assess for complications.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is based on the history, which may be from the patient, relative/friend or ambulance crew who have found empty packets of paracetamol. It is essential to consider paracetamol in any patient presenting with a mixed overdose or where the medication is unknown.

Hospital referral criteria

Any patient who has ingested paracetamol in the context of self-harm needs hospital admission for medical assessment and urgent psychiatric input.

Other reasons for hospital admission include:

- Symptomatic patients

- Ingestion of ≥75 mg/kg of paracetamol over an hour or less

- Ingestion of ≥75 mg/kg but the time of ingestion is uncertain

- Any patient who has taken a staggered overdose

- Ingestion of more than the licensed dose (4g/24 hours for adults) and the total dose is ≥75 mg/kg within 24 hours, OR, <75 mg/kg within 24 hours for each of the preceding 2+ days.

Bloods

A series of blood tests are essential to assess for hepatic damage, extra hepatic organ dysfunction and determine patients that may need urgent referral to a transplant centre.

- Full blood count

- Urea & electrolytes

- Liver function tests

- Bone profile

- Venous/arterial blood gas (pH, bicarbonate, lactate)

- Blood glucose

- Paracetamol levels

- Salicylates levels: should always be requested in acute overdose

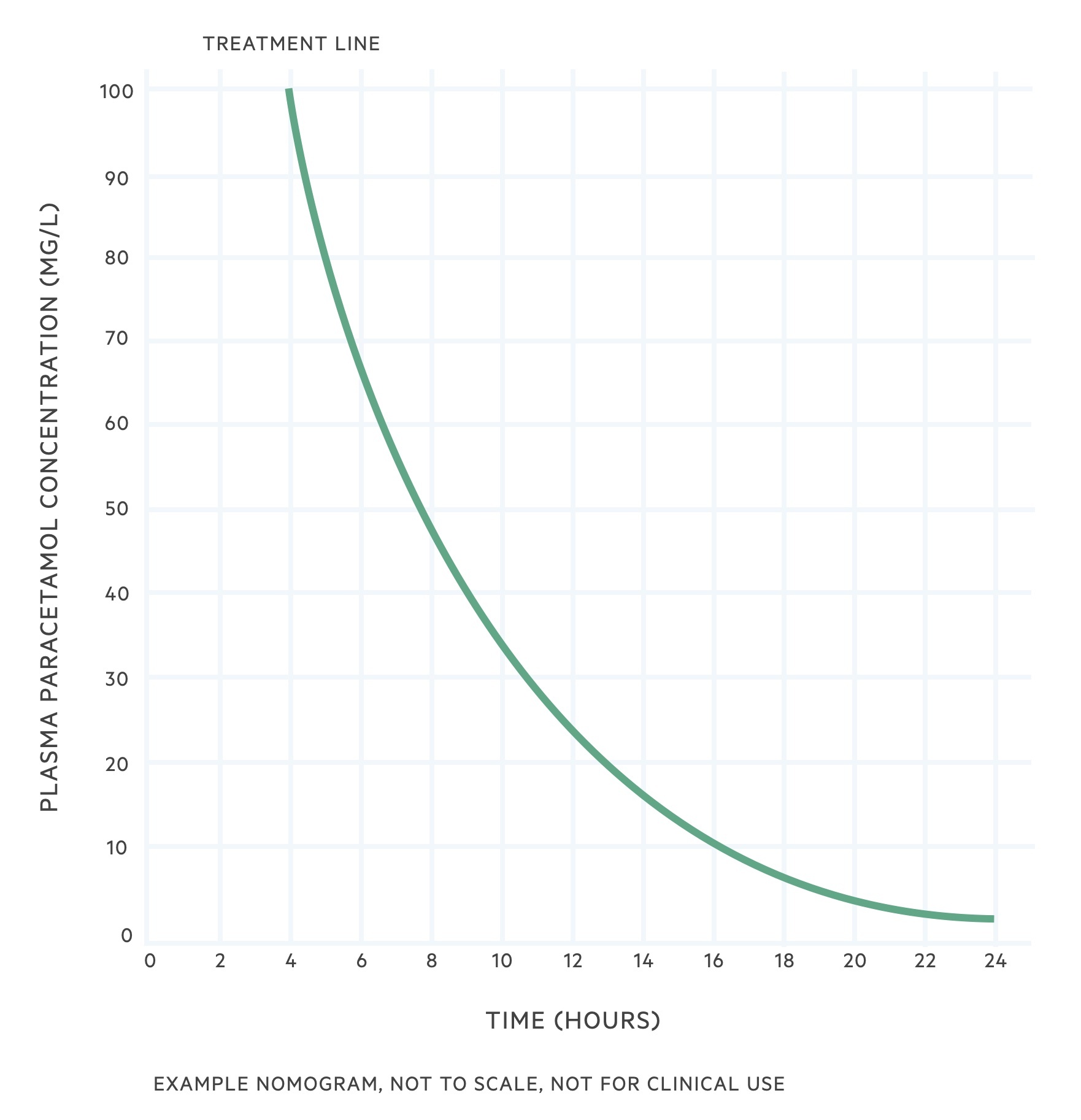

Nomogram

The paracetamol ingestion graph or ‘nomogram’ is used to determine if treatment with N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is needed.

The paracetamol nomogram is used to plot paracetamol concentration against time from ingestion. If the paracetamol concentration lies on or above the treatment line, NAC should be administered. This is used for patients who have ingested paracetamol over one hour or less and presented within 8 hours. As the plasma paracetamol concentration reaches its peak at 4 hours, it is important not to take a paracetamol level within 4 hours of the last ingestion.

Patients who have a delayed presentation, or where the paracetamol level will not be available within 8 hours from last ingestion, NAC is started whilst awaiting investigations. Paracetamol levels can be interpreted up to 24 hours, but any detectable level of paracetamol beyond 16 hours is concerning.

NAC

The principle treatment of a paracetamol overdose is N-acetylcysteine.

The principle treatment of paracetamol overdose is the intravenous administration of NAC. NAC has multiple proposed mechanisms of action. Critically, it is a precursor to glutathione, which means that administration increases the glutathione concentration available to bind NAPQI.

NAC is given as a standard 21 hour regimen, which is based on the patients weight. It comprises three consecutive infusions.

- First infusion (1 hour): 200 mls 5% dextrose or 0.9% sodium chloride with 150 mg/kg of NAC

- Second infusion (4 hours): 500 mls 5% dextrose or 0.9% sodium chloride with 50 mg/kg of NAC

- Third infusion (16 hours): 1000 mls 5% dextrose or 0.9% sodium chloride with 100 mg/kg of NAC

After the 21 hour regimen, bloods test are usually taken to look for any signs of hepatic impairment. If there is any evidence of significant coagulopathy, deranged liver function tests or abnormal renal function the patient should be discussed with the liver transplant centre. At this point, the third infusion of NAC is usually given continuously back-to-back until further advice.

Adverse effects

Anaphylactoid reactions to intravenous NAC is common and seen in up to 30% of patients treated with the 21-hour regimen. It usually occurs soon after the first infusion with features of nausea, vomiting, urticarial rash, angioedema, tachycardia, and bronchospasm. Shock is uncommon.

If this develops, temporarily stop the infusion, consider chlorphenamine (anti-histamine) and nebulised salbutamol. Once the reaction has settled, restart the infusion. Can consider slowing the infusion rate of the first bag to over 2 hours.

NOTE: an anaphylactoid reaction produces the same clinical picture of anaphylaxis but is not IgE-mediated

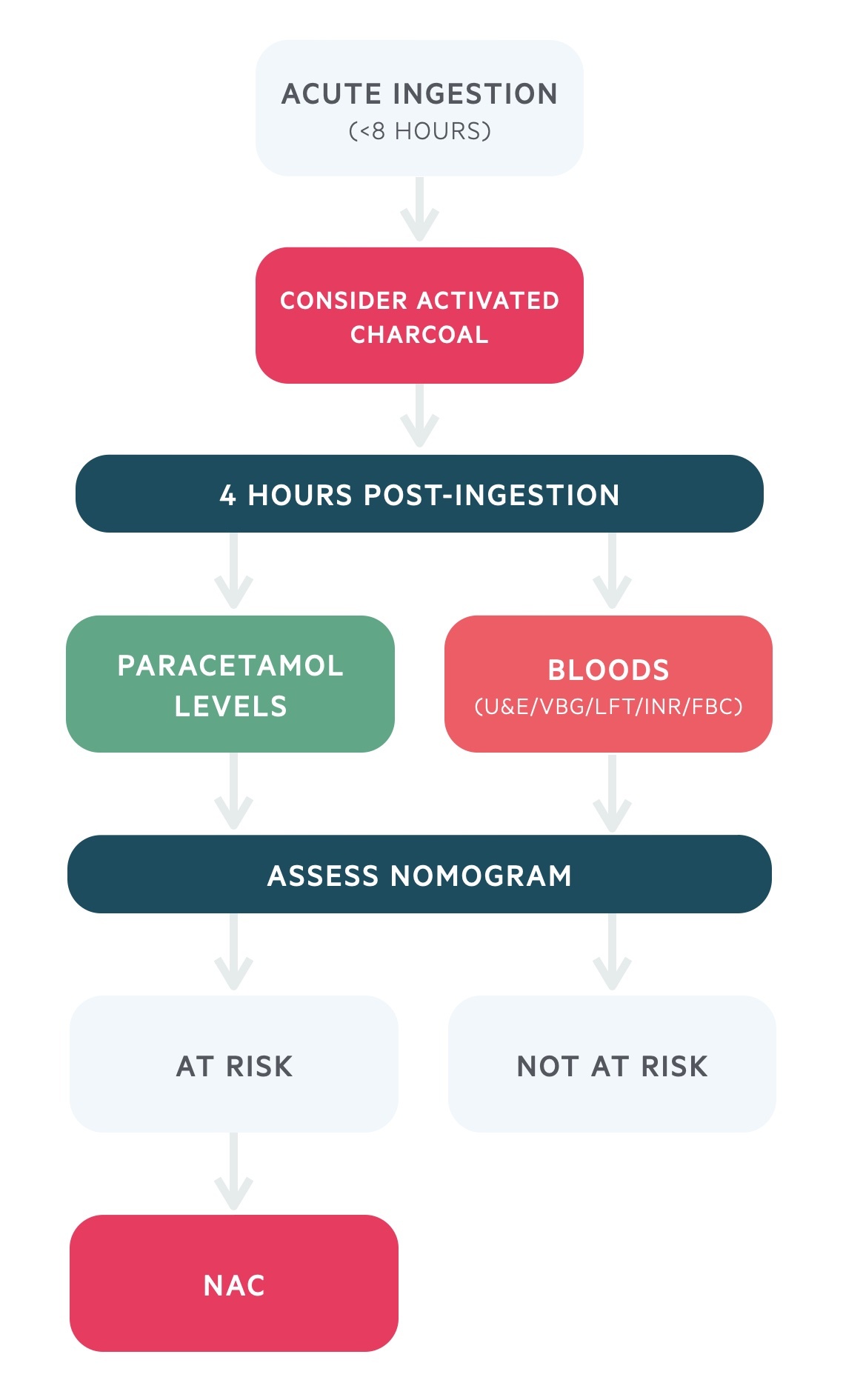

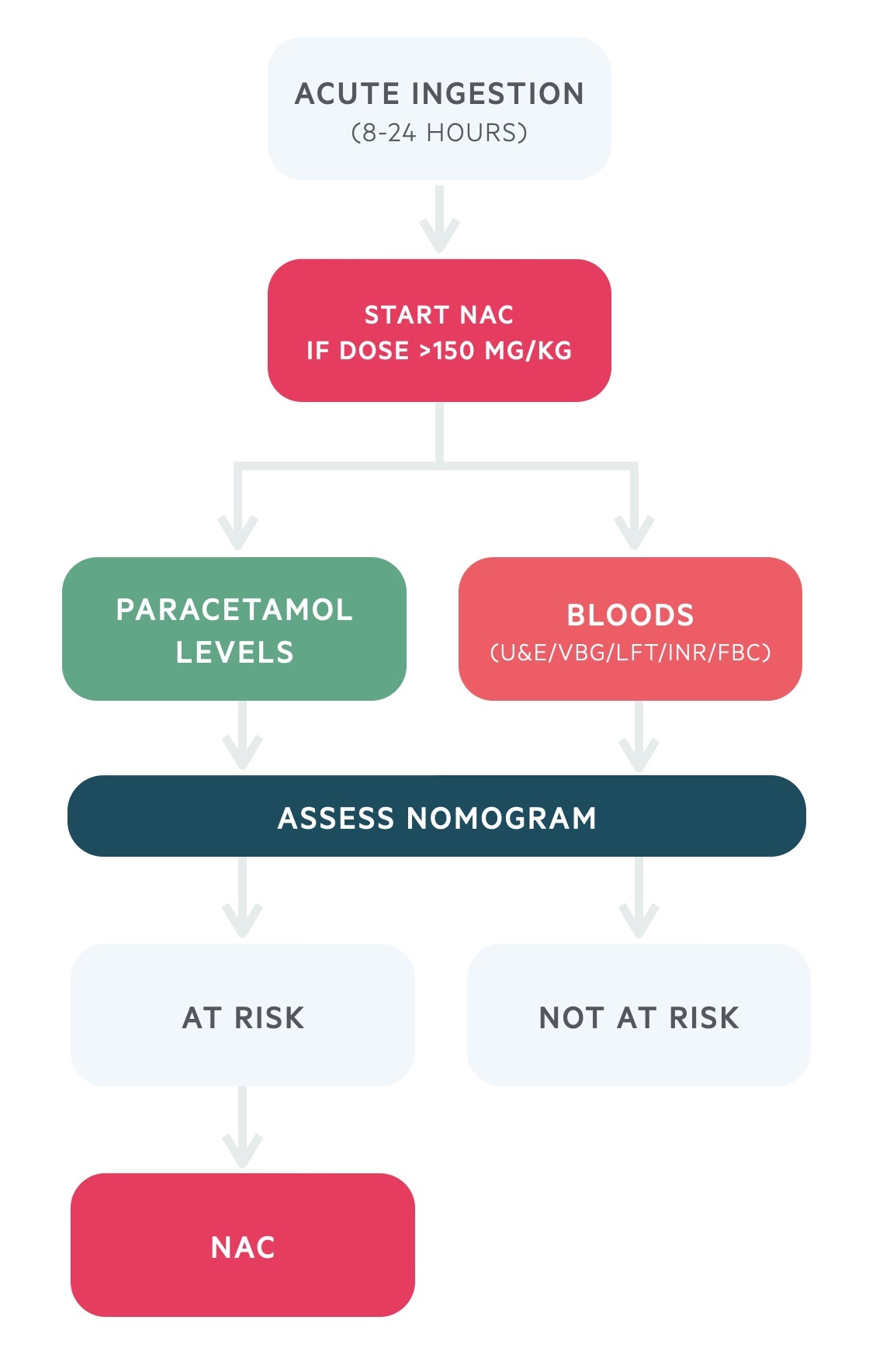

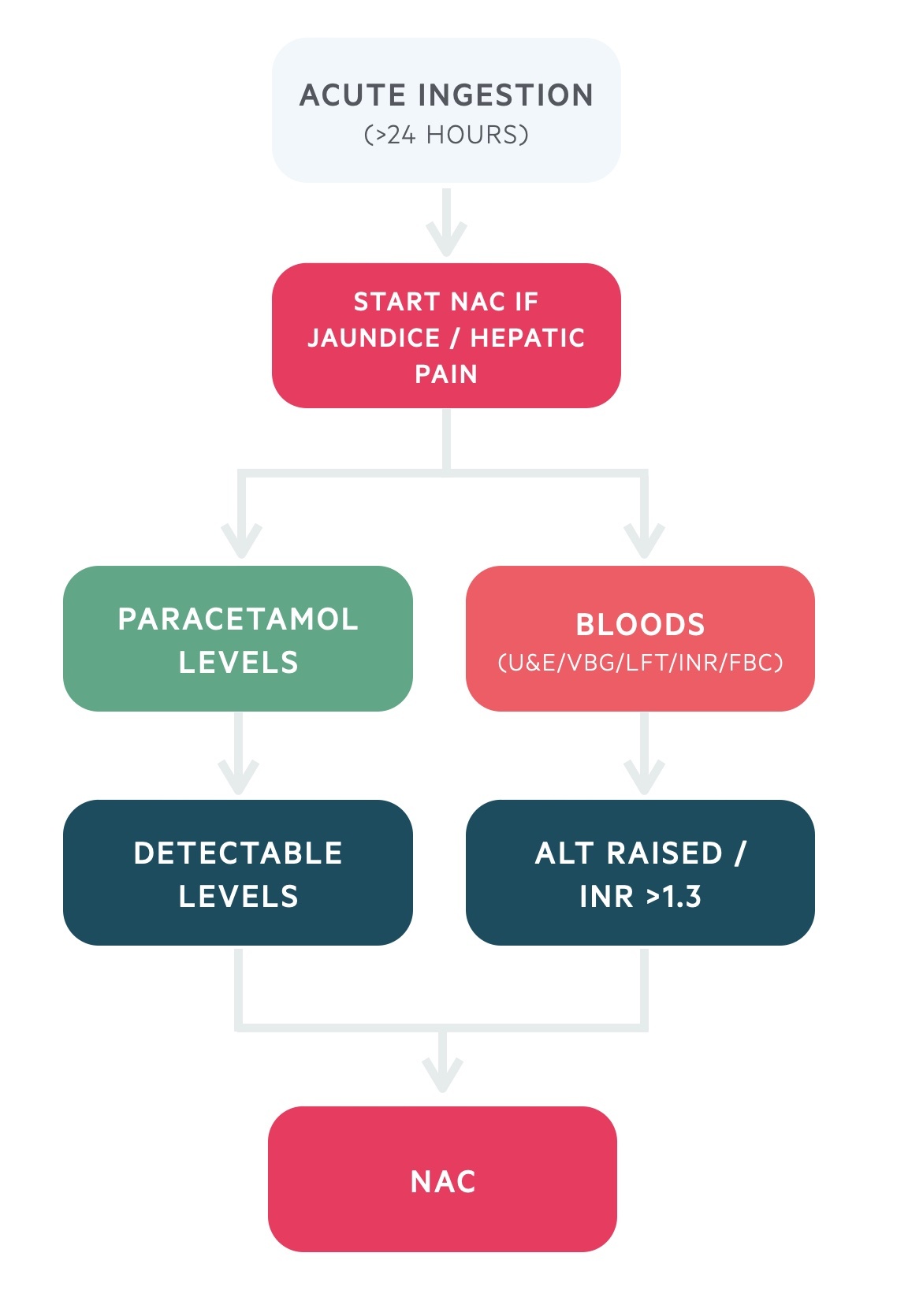

Treatment algorithm

Deciding when to initiate and continue NAC depends on the time and type of paracetamol ingestion.

All patients with a suspected paracetamol overdose should be managed according to a local treatment algorithm or follow the treatment algorithm from Toxbase. There are different algorithms depending on the type of ingestion (acute versus staggered), timing of presentation (< 8 hours, 8-24 hours, >24 hours) and presence or absence of hepatic damage.

NOTE: each diagram represents a simplified version of the treatment algorithm. Always check local guidelines or Toxbase.

Acute ingestion (< 8 hours)

- Activated charcoal: consider 50 g for adults if ingestion of >150 mg/kg and presentation within one hour

- Paracetamol level: wait until 4 hours from last ingestion then take a paracetamol level (cannot interpret level within 4 hours)

- Blood tests: takes bloods for U&Es, venous blood gas, LFTs, INR and FBC.

- Nomogram: assess the need for NAC by plotting the paracetamol level on the nomogram

- Abnormal bloods: if there is any evidence of hepatic injury consider NAC even if paracetamol level is below treatment line

- Treatment within 8 hours: if a paracetamol level will not be available within 8 hours of ingestion, start NAC empirically

- Not at risk: treatment is not required if the patient is asymptomatic, bloods are normal and paracetamol level is below the treatment line

- At risk: start/continue NAC treatment and follow end of treatment guidance

Acute ingestion (8-24 hours)

- Paracetamol level: take an urgent paracetamol level on admission

- Blood tests: takes urgent bloods for U&Es, venous blood gas, LFTs, INR and FBC.

- NAC: start NAC immediately if the patient has ingested >150 mg/kg

- Nomogram: assess the risk of liver damage by plotting the paracetamol level on the nomogram

- Abnormal bloods: if there is any evidence of hepatic injury, continue NAC regardless of paracetamol level

- Not at risk: treatment is not required if the patient is asymptomatic, bloods are normal and paracetamol level is below the treatment line. NAC can be stopped

- At risk: continue NAC treatment and follow end of treatment guidance

Acute ingestion (>24 hours)

- Paracetamol level: take an urgent paracetamol level on admission

- Blood tests: takes urgent bloods for U&Es, venous blood gas, LFTs, glucose, INR and FBC

- Immediate treatment: start NAC immediately if the patient is jaundiced or has hepatic tenderness

- Decision on NAC: treat with NAC if ALT raised, OR INR >1.3 (in absence of another cause), OR paracetamol level detected

- Not at risk: treatment is not required if the patient is asymptomatic, bloods are normal and paracetamol level is not detected.

- At risk: start NAC treatment and follow end of treatment guidance

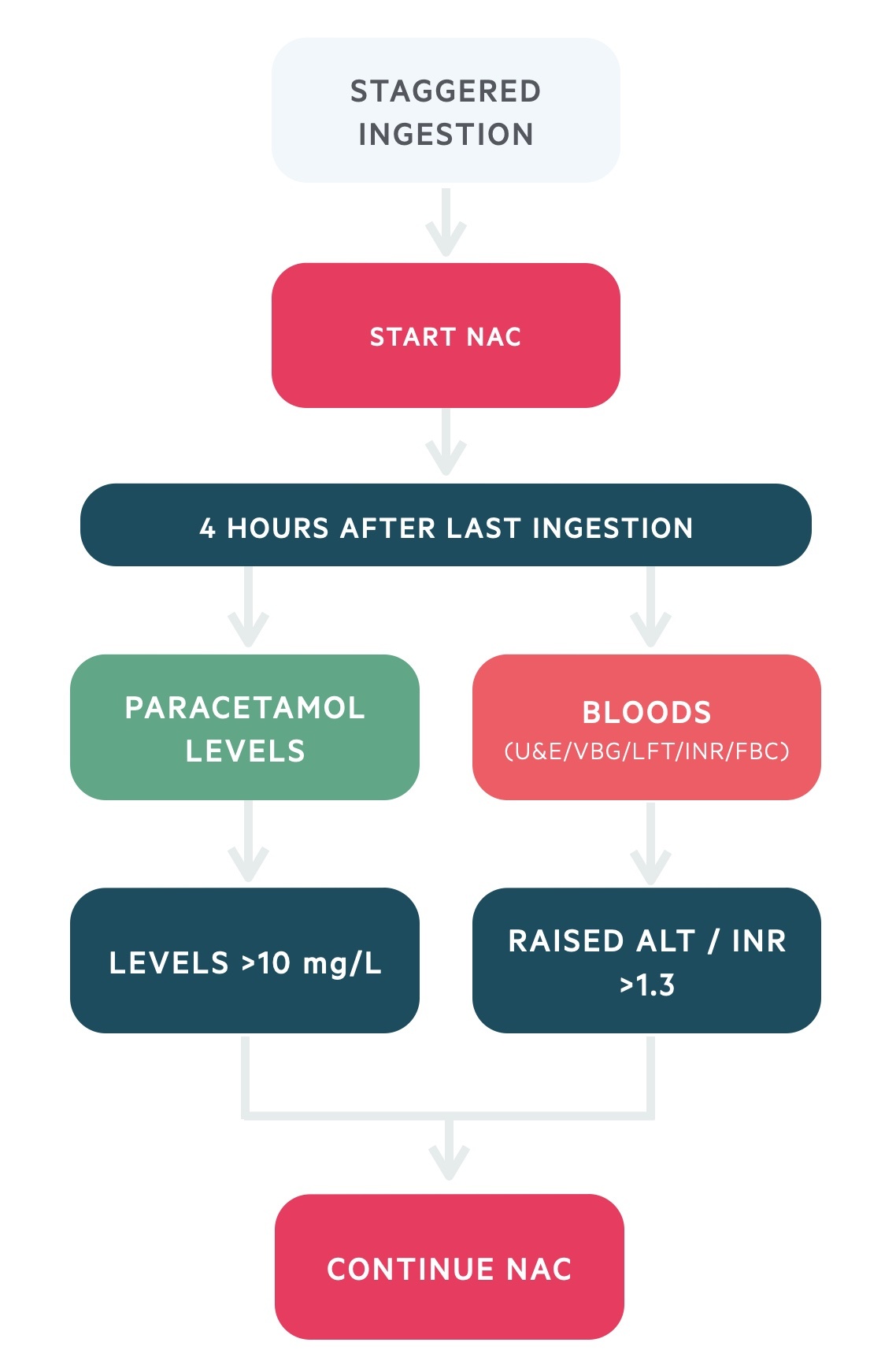

Staggered overdose

- Immediate treatment: start NAC treatment without delay in a staggered overdose

- Paracetamol level: wait until 4 hours following the last ingestion of paracetamol to take a level

- Blood tests: takes urgent bloods for U&Es, venous blood gas, LFTs, INR and FBC (should be 4 hours after ingestion)

- Not at risk: clinically significant hepatotoxicity is unlikely if >4 hours since last paracetamol ingestion AND paracetamol concentration <10 mg/L, ALT normal, INR ≤1.3 and no symptoms of hepatic damage

- Discontinuing NAC: if the patient is not at risk, discontinue NAC

- Continuing NAC: if the patient has symptoms of hepatic damage, paracetamol concentration >10 mg/L or raised ALT and/or INR >1.3 then continue NAC and follow end of treatment guidance

End of treatment

At the end of the standard 21-hour infusion of NAC, patients need to undergo repeat blood tests for LFTs, U&Es, INR and venous blood gas.

Treatment may be stopped when:

- INR ≤1.3 and ALT within normal range, OR

- INR ≤1.3 and ALT raised but <2x upper limit of normal and not more than double admission ALT

Treatment with NAC should be continued when:

- ALT >2x upper limit of normal

- ALT is raised and more than double the admission ALT

- ALT is raised and INR >1.3 (in absence of another cause)

- INR >0.5 from admission value

NOTE: if isolated rise in INR <0.5 from admission value, stop NAC and repeat INR in 4-6 hours. If INR falling or unchanged and ALT <2x upper limit of normal, no further treatment required.

Acute liver failure

Paracetamol overdose is the most common cause of ALF requiring liver transplantation in the UK.

Paracetamol overdose can lead to life-threatening ALF requiring urgent referral to a liver transplant centre for consideration of liver transplantation. These patients require management in an intensive care unit with specialist hepatology input. For more information see our notes on acute liver failure.

The decision to refer a patient to a liver transplant centre is based on guidance by the European association for study of the liver (EASL). In addition, the decision to allocate an urgent liver transplant is based on the King’s college criteria.

Referral criteria

- Arterial pH: <7.30 or bicarbonate <18 mmol/L

- INR: >3.0 on day 2 or >4.0 thereafter

- Renal: Oliguria or elevated creatinine

- Mental status: Altered consciousness (i.e. HE)

- Glucose: Hypoglycaemia

- Lactate: Elevated lactate unresponsive to fluid resuscitation

King’s college criteria

- Arterial pH: <7.3 after resuscitation and >24 h since ingestion

- Lactate: >3 mmol/L, OR

- The 3 following criteria:

- Hepatic encephalopathy >grade 3

- Serum creatinine >300 umol/L

- INR >6.5

Liaison psychiatry

Any patient who has ingested paracetamol in the context of self-harm needs an urgent psychiatric assessment.

Liaison Psychiatry refers to a dedicated team that can provide psychiatric input in general hospitals for patients who have mental health problems. This is critical for patients who have presented with self-harm or overdose. Traditionally, overdose and poisoning represents up to 10% of medical admissions.

The liaison psychiatry team are able to assess a patients ongoing suicidal risk and need for ongoing mental health input. Some of the considerations the team can assess include:

- Risk: ongoing suicidal ideation and risk to themselves

- Mental health act: need for section under the mental health act

- Observation: need for RMN 1:1, which refers to a registered mental health nurse sitting with the patient at all times

- Further input: need for ongoing psychiatric input as an inpatient

- Inpatient psychiatric care: need for transfer to an inpatient mental health bed once medically cleared

- Outpatient psychiatric care: need for outpatient mental health input

Last updated: March 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback