Hepatitis E

Notes

Overview

Hepatitis E is a small, non-enveloped RNA virus that can lead to acute and chronic hepatitis.

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) was originally considered a disease of travellers returning from endemic areas where it can cause large outbreaks. However, it is now recognised as the most common cause of acute viral hepatitis in many countries.

HEV is spread via the faeco-oral route, leading to locally-acquired infections or epidemic outbreaks.

The spectrum of HEV is wide and depends on the underlying genotype (see chapter on hepatitis E virus), patient co-morbidities (e.g. immunosuppressed or immunocompetent) and pregnancy status. It can cause:

- Asymptomatic infections

- Acute viral hepatitis

- Chronic viral hepatitis

- Extra-hepatic manifestations

Hepatitis E virus

There are four genotypes of hepatitis E that can cause disease in humans.

HEV belongs to the genus Orthohepevirus within the family Hepeviridae. There are four genotypes of mammalian HEV that are known to affect humans:

- HEV1

- HEV2

- HEV3

- HEV4

HEV1 and HEV2

These genotypes are waterborne obligate human pathogens. They usually cause epidemics of hepatitis E in developing countries and are most commonly seen in travellers returning from endemic areas. HEV1 is mostly found in Asia, while HEV2 is more commonly seen in Africa and Mexico.

HEV3 and HEV4

These genotypes are responsible for sporadic cases in developed and developing countries. In the UK, autochthonous (locally-acquired) HEV3 is the most common cause of hepatitis E and the genotype is widespread in Europe. HEV4 is largely restricted to Southeast Asia, but an increasing number of cases are being identified in Europe.

HEV3 and HEV4 are considered a porcine zoonotic infection, although they have been identified in other mammalian species including rates, wild board and rabbits. The primary host is pigs, but it is apathogenic in these animals. Eating contaminated pig meat or water can transmit the virus.

Epidemiology

There is an estimated two million locally acquired HEV infections in Europe every year.

Across Europe, there are areas of hyperendemic HEV (predominantly genotype 3). These include Southwest France, Netherlands, Scotland, western Germany, Czech Republic, Abruzzo, central Italy and western/central Poland.

Genotypes 1 and 2 are more prevalent in developing countries.

Seroprevalence and blood donors

Seroprevalence data has been assessed in blood donors, which shows high levels of IgG seropositivity that implies previous infection. This may be as high as 50% in areas of France to only 6% in Australia.

A significant proportion of donors are viraemic (i.e. high levels of HEV virus in the blood) at the time of donation, which can be transmitted to the recipient. This may be as high as 1:600 in areas of the Netherlands. The has led to many blood banks screening for HEV to protect high risk individuals receiving regular transfusions (e.g. patients with leukaemia).

Pathophysiology

The incubation period of hepatitis E is 2-6 weeks.

HEV is transmitted via the faeco-oral route. HEV1 and HEV2 are generally transmitted through contaminated water, whereas HEV3 and HEV4 are considered zoonotic infections, acquired from infected animals (usually contaminated meat or infected water from the run off of slurry).

Once acquired, the incubation period is 2-6 weeks. This describes the period between exposure to the virus and development of clinical symptoms. HEV viraemia reaches its peak during the early infectious period, which is associated with a transient rise in IgM (acute antibody response) followed by a more sustained IgG response. During this acute infection, viral RNA may be detected in the blood or stool. It disappears from the blood within 3 weeks. The narrow viraemic window means the absence of viral RNA does not exclude acute infection.

The vast majority have a subclinical infection. In fact, < 5% of patients with HEV3 will develop clinical hepatitis. Patients who do develop a clinically apparent acute infection usually have a self-limiting illness. However, the condition is associated with several extrahepatic manifestations (see clinical features). In patients with pre-existing liver disease, there is an increased risk of decompensated cirrhosis or acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF).

Patients who are immunosuppressed are at risk of chronic infection (presence of HEV for > 3 months) and accelerated liver disease.

Clinical features

Locally-acquired hepatitis E is more common in middle-aged/elderly males.

Asymptomatic illness

The majority of patients with acute hepatitis E will have a subclinical illness.

Acute hepatitis

Most patients with acute hepatitis will have a self-limiting illness with spontaneous recovery

- Jaundice

- Fatigue

- Nausea & vomiting

- Abdominal pain

- Pruritus

- Flu-like illness

- Hepatomegaly

Chronic hepatitis

Chronic hepatitis E refers to the presence of HEV in the blood or stool for > 3 months. It is more likely to occur in patients who are immunosuppressed (e.g. post-transplantation) and can lead to a rapid development of fibrosis/cirrhosis.

- Commonly asymptomatic

- Fatigue

- Rarely jaundiced

Acute liver failure

Acute liver failure can occur with HEV, but is rare with HEV3. Patients with pre-existing disease are at increased risk of ACLF. In pregnancy, acute hepatitis can be devastating with a 20% mortality.

Extra-hepatic manifestations

This refers to a variety of clinical presentations occurring outside the liver:

- Neurological: brachial neuritis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, mononeuritis multiplex, meningoencephalitis.

- Renal: glomerulonephritis (IgA, membranoproliferative, membranous).

- Haematological: thrombocytopenia, monoclonal gammaopathy of unknown significance (MGUS), cryoglobulinemia

- Gastrointestinal: acute pancreatitis

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on the presence of HEV RNA or positive serology (IgM/IgG).

Patients with symptomatic acute hepatitis usually have marked elevations in liver transaminases (e.g. ALT/AST >1000 IU/L). However, liver enzyme derangement is variable and in patients with chronic hepatitis E it may be much less prominent.

Any patient with biochemical evidence of hepatitis should be tested for hepatitis E.

HEV RNA

Blood tests can be taken for HEV RNA, which is detected using PCR. This confirms the presence of acute or chronic HEV. However, due to the short window of viraemia, a negative result does not exclude acute HEV.

HEV serology

The detection of anti-HEV antibodies can be used to make the diagnosis of hepatitis E. Although IgM is the initial antibody response and suggests acute infection, by itself, it is not robust enough to make the diagnosis of acute HEV.

Antigen assays

Detection of HEV antigens may be used to diagnose acute and chronic infection.

Diagnostic interpretation

Acute infections

- HEV RNA

- HEV RNA + anti-HEV IgM

- HEV RNA + anti-HEV IgG (usually IgM negative on reinfection)

- HEV RNA + anti-HEV IgM + anti-HEV IgG

- Anti-HEV IgM + anti-HEV IgG (rising)

- HEV antigen positive

Chronic infection

- HEV RNA ≥ 3 months (+/- anti-HEV antibodies)

Past infection

- Anti-HEV IgG positive only

Investigations

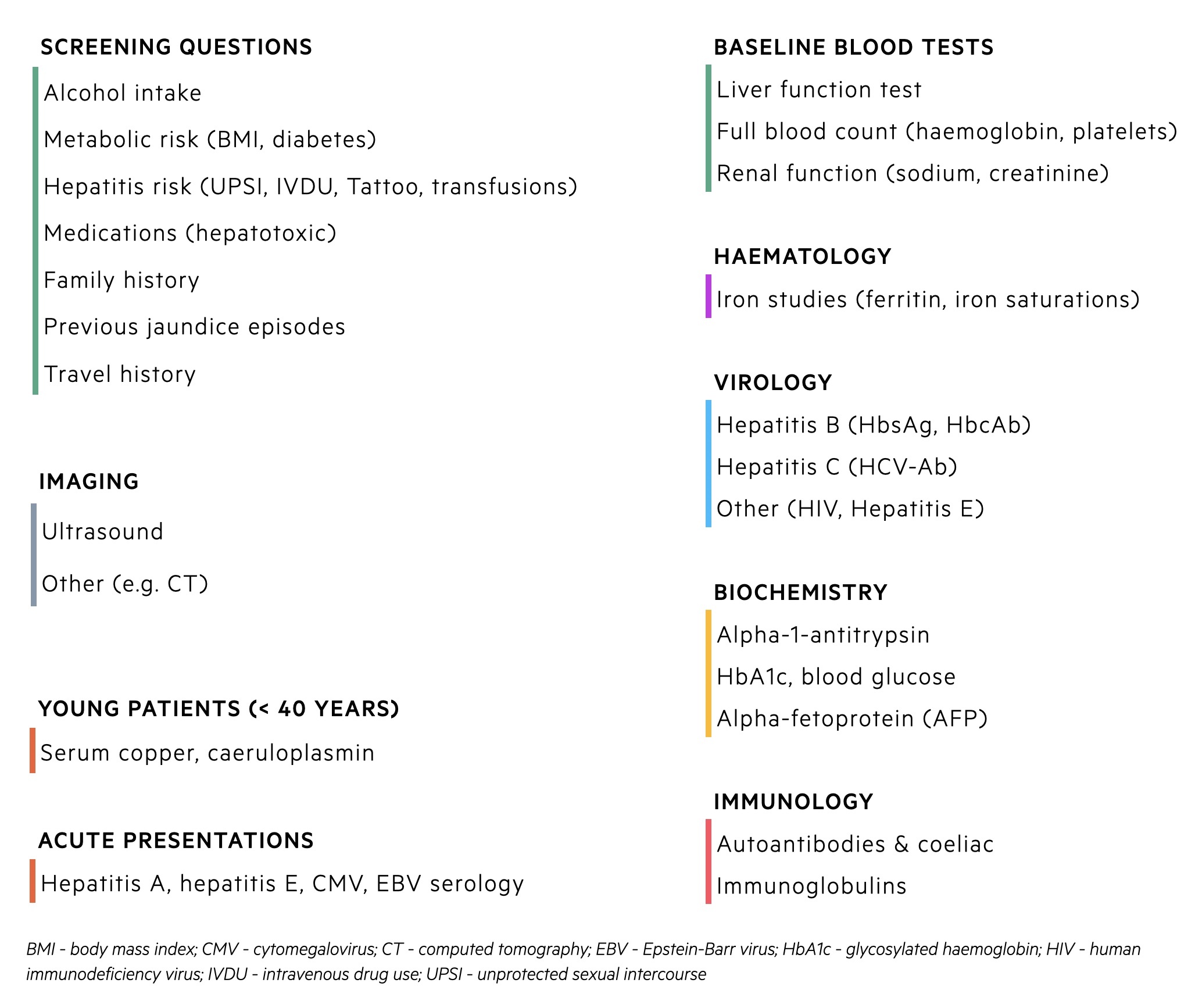

A series of investigations are requested in any patient with a new derangement in liver function tests.

At presentation, it may be unclear why a patients liver function tests are abnormal. Consequently, new derangement in liver function tests, particularly a transaminitis (rise in ALT/AST) requires a series of investigations known as a non-invasive liver screen. Hepatitis E testing is mandatory in acute hepatitis.

Non-invasive liver screen

A non-invasive liver screen refers to screening questions, biochemical tests and imaging to assess patients with suspected liver disease. It is employed when blood tests show abnormal liver function or patients have evidence of chronic liver disease on clinical examination/imaging.

Testing for Hepatitis E

All patients with acute hepatitis or decompensated cirrhosis should be tested for acute hepatitis E.

Due to the number of extrahepatic manifestations associated with hepatitis E, the following conditions should warrant HEV IgM/IgG and RNA testing

- Suspected drug-induced liver injury

- Brachial neuritis

- Guillain-Barré syndrome

- Encephalitis

- Patients with unexplained acute neurology and a raised ALT/AST

Management

Acute hepatitis E does not usually require any treatment and management is supportive.

Supportive treatment

In the majority of patients, acute hepatitis E will clear spontaneously. Advice consists of good oral hydration and rest. Alcohol should be avoided. Patients liver function tests and synthetic function (i.e. INR, albumin, bilirubin) can be monitored to ensure no worsening.

Acute liver failure or decompensated cirrhosis

A small proportion of patients may develop acute liver failure (ALF) or decompensated cirrhosis in those with underlying chronic liver disease. For more information on the management of ALF and decompensated cirrhosis, please see our other notes:

Anti-viral therapy

Ribaviron is the anti-viral therapy of choice and usually reserved for patients with chronic hepatitis E that has failed to clear spontaneously. Chronic hepatitis E most commonly occurs in immunosuppressed patients so the first management strategy is reduction in immunosuppression if possible. If this fails to clear the virus, ribaviron can be considered.

Ribaviron is typically given as a three month course of treatment that can be extended 6 months if there is clinical relapse. Other options include a 3 month course of Pegylated interferon in liver transplant patients. This is reserved for those who failed to respond to ribaviron.

Liver transplantation

Chronic hepatitis E may lead to progressive fibrosis/cirrhosis. Liver transplantation is a potential option in these patients.

Vaccination

In China, a vaccine against HEV has been licensed since 2011. The vaccine is derived against a component of HEV genotype 1 and has been shown to prevent episodes of symptomatic acute hepatitis. The longterm safety in patients who are immunosuppressed or with chronic liver disease is unknown. Outside China, the vaccine is not licensed for use.

Complications

Chronic hepatitis E can lead to rapidly progressive fibrosis and acute hepatitis E rarely causes ALF.

Hepatic complications

- Fulminant hepatitis in pregnancy (20% mortality)

- Decompensated cirrhosis or ACLF

- Acute liver failure

- Rapidly progressive fibrosis (chronic hepatits E)

Extrahepatic complications

- Neurological: wide variety of neurological problems associated with hepatitis E (e.g. Guillain-Barré syndrome, brachial neuritis)

- Haematological: thrombocytopaenia, MGUS

- Renal: glomerulonephritis

- Other: pancreatitis, autoimmune thyroiditis, polyarthritis, among others.

Last updated: March 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback