Budd-Chiari syndrome

Notes

Overview

Budd-Chiari syndrome is a vascular liver disorder due to obstruction of hepatic venous outflow.

Budd-Chiari syndrome (BCS) describes a classic triad of hepatomegaly, abdominal pain and ascites due to hepatic venous obstruction. It is a vascular liver disease due to a variety of underlying disorders that each result in obstruction anywhere from the small hepatic venules in the liver to the entrance of the inferior vena cava (IVC) at the right atrium.

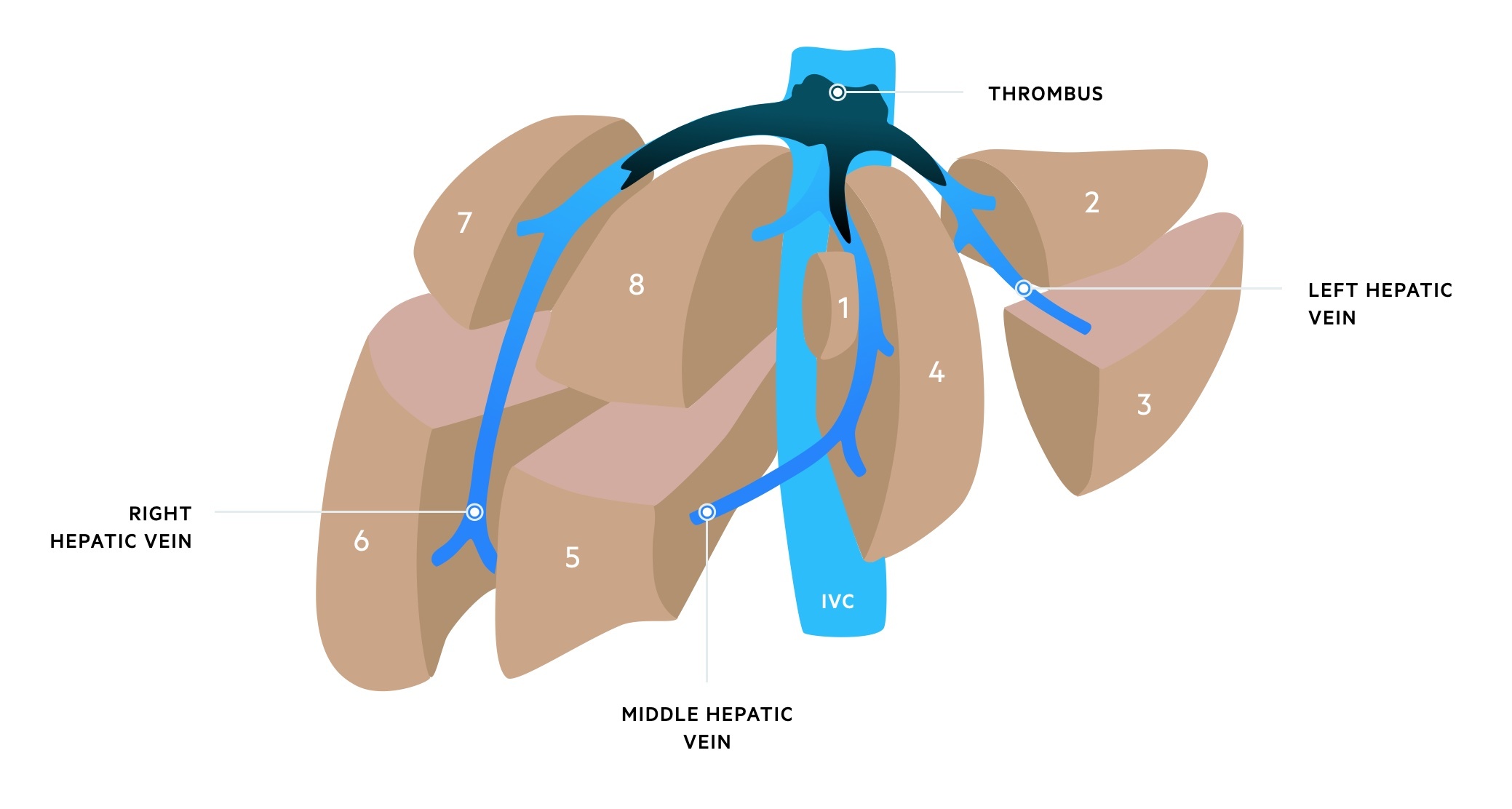

Budd-Chiari syndrome with thrombus in all three hepatic veins

Epidemiology

In the general population, BCS occurs at 1 in 100,000 people.

The epidemiology of BCS varies depending on geographical location. In non-Asian countries, the condition typically presents in the third or fourth decade and is slightly more common in woman. The condition can occur in children and the elderly. BCS is being more frequently diagnosed, which likely reflects the increasing use of imaging.

Terminology

Several important terms are used to describe hepatic venous outflow obstruction in the liver.

BCS is often used as a broad term to refer to hepatic venous outflow obstruction. It can be divided into primary or secondary:

- Primary BCS: obstruction due to a predominantly venous process (e.g. thrombosis, phlebitis)

- Secondary BCS: obstruction due to external compression or invasion of the hepatic veins/IVC (e.g. tumour)

Several more exact terms are used to describe the pathological process of venous outflow obstruction that incorporates both the level of obstruction and suspected aetiology. These terms represent separately discussed conditions with different management strategies. In this context, the term BCS is used to refer to a much more specific pathological process.

The key terminology include:

- Budd-Chiari syndrome

- Sinusoidal obstructive syndrome

- Congestive hepatopathy

- Obliterative hepatocavopathy

Budd-Chiari syndrome

Describes a condition characterised by occlusion or partial occlusion of any, or all, the three major hepatic veins. This may occur with or without occlusion of the IVC. Commonly due to thrombosis with well characterised underlying conditions including myeloproliferative disorders (50% of cases).

Sinusoidal obstructive syndrome

Sinusoidal obstructive syndrome (SOS) is also known as veno-occlusive disease. It specifically refers to obstruction of the hepatic sinusoids and small hepatic venules. This type of obstruction is commonly due to nonthrombotic fibrosis or obliteration that may be induced by drugs (e.g. chemotherapy).

Congestive hepatopathy

This describes several conditions that result in hepatic congestion due to cardiac or pericardial disease. Commonly the result of right-sided heart failure, tricuspid regurgitation or constrictive pericarditis. Due to the very specific aetiology, considered separately.

Obliterative hepatocavopathy

This refers to a very specific condition where there is membranous obstruction in the IVC that predisposes to thrombosis. A thick fibrous band or web may develop blocking flow through the IVC. More frequently seen in Asian countries (e.g. Japan). Usually a milder version of BCS.

Aetiology

The cause of BCS can be identified in up to 80% of cases.

The majority of conditions leading to Budd-Chiari are associated with a hypercoagulable state that increases the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE). Most importantly, myeloproliferative disorders are implicated in up to 50% of cases.

Causes of BCS

- Myeloproliferative disorders

- Malignancy

- Infection and benign liver lesions

- Oral contraceptives and pregnancy

- Other: hypercoaguable states, membranous webs, connective tissue diseases (e.g. Behçet, lupus)

Myeloproliferative disorders

The myeloproliferative disorders (MPD) refers to several haematological conditions that are characterised by an overproduction of cells derived from the myeloid cell line in the bone marrow.

MPD is essentially an umbrella term for several condition, which include (among others):

- Polycythaemia ruba vera (PRV): overproduction of erythrocytes

- Essential thrombocytosis (ET): overproduction of platelets by megakarocytes

- Chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML): one of the chronic leukaemias with overproduction of leucocytes.

MPD are implicated in up to 50% of cases of BCS, particularly with PRV. The presence of a MPD may be ‘occult’ or ‘covert’ and only identified on bone marrow assessment. Patients are commonly tested for the characteristic JAK2 mutation that is found in >80% of patients with PRV as well as other MPD disorders. This mutation renders haematopoietic cells more sensitive to growth factors.

Malignancy

Malignancy, or cancer, accounts for around 10% of BCS cases and may be primary (due to thrombosis) or secondary (due to tumour invasion or compression). Hepatocellular carcinoma is most often implicated.

Infection and benign liver lesions

A variety of benign liver lesions including hepatic cysts, hepatic abscesses, adenomas or fungal infections (e.g. aspergillosis) can lead to thrombosis or extrinsic compression.

Oral contraceptives and pregnancy

The cause of BCS may be related to contraceptive use or pregnancy in up to 20% of cases. This is thought to be due to the increased sex hormone levels in these conditions that promotes a hypercoagulable state.

Others

Numerous other conditions may lead to BCS. This could be due to a condition that promotes a hypercoagulable state (e.g. factor V leiden) or a systemic inflammatory condition that causes a global pro-coagulable state (e.g. Behçet, Lupus). Only 20% of BCS cases are considered idiopathic (no known cause).

Pathophysiology

The severity of BCS depends on the speed of occlusion and time for collateral formation.

For the clinical spectrum of BCS, occlusion of ≥2 hepatic veins is usually required. Occlusion increases the pressure in hepatic sinusoids, which reduces blood flow, causes dilatation and leads to interstitial fluid accumulation. When the lymphatic capacity for clearing the interstitial fluid is exceeded, it passes through the liver capsule and causes ascites.

This global increase in pressure reduces portal flow and leads to hypoxic damage to hepatocytes. Due to poor portal flow, portal vein thrombosis may be seen in 10-20% of cases. As the condition progresses there is centrilobar necrosis (cell damage around the central veins in the liver architecture). This area is known as zone 3. Rapid progression to acute liver failure, or slow progression of fibrosis, depends on the speed of occlusion.

Speed of occlusion

BCS may lead to acute (fulminant) liver failure or rapid progression of fibrosis with development of cirrhosis. This spectrum of severity is dependent on the speed of occlusion to the hepatic venous flow.

- Acute occlusion: patients at risk of acute liver failure that can result in death within 2-3 weeks.

- Subacute occlusion: more insidious onset over months compared to acute occlusion. Less severe due to collateral venous formation in portal and hepatic venous systems. At risk of rapid progression of fibrosis.

- Chronic occlusion: development of chronic liver disease with features of portal hypertension. Usually present with complications of cirrhosis (e.g. ascites, encephalopathy)

Clinical features

Traditionally, BCS is characterised by a triad of hepatomegaly, abdominal pain and ascites.

The clinical features of BCS are highly variable. Up to 15% of patients may be asymptomatic, which is usually due to hepatic venous collaterals (e.g. patency of one large remaining hepatic vein). Other patients may present with acute liver failure, characterised by ascites, encephalopathy, jaundice and coagulopathy.

Symptoms

- Abdominal pain

- Abdominal swelling (ascites)

- Nausea & vomiting

- Itching

- Leg cramps

- GI bleeding: more common if acute presentation with/without liver failure

Signs

- Hepatomegaly

- Ascites

- Distended abdominal veins (predominant if IVC obstruction)

- Peripheral oedema (predominant if IVC obstruction)

- Jaundice (usually absent and at worst mild)

Features of acute liver failure

- Hepatic encephalopathy: confusion, asterixis (flapping tremor)

- Bruising (coagulopathy)

- Jaundice

- Ascites

- GI bleeding (e.g. variceal)

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of BCS is made by demonstrating hepatic venous outflow obstruction on imaging.

The diagnosis of BCS is made using imaging. Options include:

- Doppler ultrasound: first-line investigation. Sensitivity >75% in experienced hands.

- CT/MRI: used if doppler ultrasound is not available, to confirm the diagnosis following ultrasound or when ultrasound is negative but the suspicion is still high. MRI is more difficult to obtain acutely compared to CT.

- Venography: involves transvenous insertion of a catheter via the internal jugular or femoral vein. Contrast is then injected to visualis the hepatic venous system once accessed. May be used if CT/MRI are inconclusive or to plan for therapeutic interventions. Considered the gold-standard.

Investigations

A comprehensive work-up is important to determine the underlying cause.

Basic investigations are important in the work-up of BCS to assess for an underlying cause, degree of liver injury and any contraindications to therapeutic options (e.g. anticoagulation and thrombolysis).

Basic investigations

- Full blood count

- Urea & electrolytes

- Liver function tests

- Bone profile

- C-reactive protein

- Coagulation

Further investigations

- Non-invasive liver screen: biochemical tests and imaging to assess patients with suspected liver disease. Important to address any additional contributors to liver disease.

- Imaging (liver US, CT, MRI): to assess for underlying malignancy or tumour causing extrinsic compression. Critical as part of both diagnosis of BCS and work-up for underlying cause.

- Thrombophilia screen: refers to testing for an inherited tendency to develop venous thromboembolism (VTE). Includes testing for deficiency of natural anticoagulants (e.g. antithrombin III, Protein C, Protein S), genetic mutations (e.g. factor V Leiden, prothrombin mutation) and antiphospholipid screen (Lupus anticoagulant, anti-Cardiolipin and anti-β-2-Glycoprotein-1 antibodies).

- Haematological screen: assessing for myeloproliferative disorders (e.g. full blood count, blood film, JAK2 mutation +/- bone marrow biopsy) and paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria.

- Liver biopsy: rarely needed in BCS, but may be completed when the diagnosis is uncertain.

- Other investigations: guided by the presentation. For example, vasculitis screen if a connective tissue disease is suspected or lower GI endoscopy if inflammatory bowel disease is suspected.

Management

A stepwise algorithm to the treatment of BCS is recommended.

Patients with BCS may present with rapid deterioration in liver function and acute liver failure. They should be referred to a specialist liver unit with access to interventional radiology and transplant services.

There are three key areas to management:

- Treat the underlying obstruction (commonly due to thrombosis): involves four key elements including medical management (e.g. anticoagulation), interventional radiology, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPSS) and liver transplantation.

- Treat the consequences of portal hypertension (e.g. ascites, varices): typically involves use of diuretics and/or ascitic drainage. Varices are managed with beta blockers or variceal band ligation for primary prophylaxis against bleeding.

- Treat the underlying condition (e.g. MPD)

Medical management

Patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome (hepatic vein thrombosis) should receive systemic anticoagulation to reduce clot extension and new thrombotic episodes. The initial anticoagulant of choice is usually low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) that may subsequently be converted to warfarin.

The presence of varices, if adequately controlled, is not a contraindication to anticoagulation.

Interventional radiology

Patients may be considered for interventional radiological procedures that include angioplasty (unblocking a vein using balloon dilatation) with/without stenting and/or catheter-directed thrombolysis.

TIPSS

Patients who fail to respond to medical therapy with anticoagulation and first-line interventional procedures may be considered for TIPSS. TIPSS is another interventional radiology procedure, which is a definitive treatment.

TIPSS involves creation of an artificial channel between the portal inflow and hepatic vein outflow. This channel is known as a shunt and is kept open by placement of a PTFE-covered stent.

Surgery

Patients presenting with severe acute liver failure or those failing to respond to medical and/or radiological therapy may be considered for liver transplantation unless significant contraindications exist. It is important to consider the patients co-morbidities, fitness for surgery and general health before proceeding to transplantation.

Survival with liver transplantation is similar to patients initially treated with TIPSS. Some patients may benefit from direct referral to transplantation rather than undergoing TIPSS, but this is a very specialist area.

Prognosis

Prognosis has improved with overall survival 75% at 5 years.

Acute forms of BCS with acute liver failure is usually fatal without liver transplantation. The use of TIPSS and liver transplantation has improved outcomes with 75% survival at 5 years. Follow-up is important because patients are at risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma following an episode of BCS.

Last updated: July 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback