Deep vein thrombosis

Notes

Overview

Deep vein thrombosis is a common condition due to partial or total occlusion of a deep vein.

Venous thromboembolism

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a term that encompasses two conditions:

- Pulmonary embolism (PE): acute/chronic occlusion of pulmonary arteries. Clot breaks off and travels to the lungs (emboli).

- Deep vein thrombosis (DVT): acute/chronic occlusion of deep vein(s). Commonly affects the lower limbs through the formation of a clot forms (thrombus).

VTE is commonly asymptomatic, but 1-2 per 1000 people every year have symptomatic VTE. DVT accounts for two thirds of these cases and is commonly seen with PE. It is estimated that 80% of cases of PE are associated with DVT.

Deep vein thrombosis

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) refers to formation of a thrombus (blood clot) that develops in one of the deep veins. This characteristically occurs within the lower limb, but can affect any deep vein (e.g. upper limb, portal vein).

Left untreated, the clot is at risk of dislodging and being carried to the lungs where it can occlude the pulmonary arteries and cause a pulmonary embolism (PE).

Location

DVT can be categorised according to the location of thrombus.

- Distal: below the popliteal trifurcation. Most likely to resolve spontaneously without symptoms.

- Proximal: above the popliteal trifurcation. May affect popliteal, femoral, or iliac veins. 50% of symptomatic patients develop PE within 3 months.

- Other: named according to the vessel or location of the thrombus (e.g. upper limb DVT, portal vein thrombus, internal jugular thrombus).

In clinical practice, DVT is generally used synonymously with a lower limb DVT (proximal or distal). DVTs affecting other locations are less common, usually require specialist input, and management pathways are different. Therefore, they are usually considered separately.

Aetiology

DVT can be caused by a condition, or state, that increases the risk of blood clots.

DVT can broadly be divided into provoked (i.e. associated with a condition, or state, that increases the risk of blood clot) or unprovoked (i.e. no identifiable cause for blood clot formation).

- Provoked: transient or persistent risk factors. Factor usually easily removed. Typically within three months of event

- Unprovoked: no readily identifiable risk factor for VTE. Not easily correctable.

Risk factors

Several conditions greatly increase the risk of blood clots. These are part of the standard VTE risk assessment in secondary care.

Due to the high risk of VTE in patients admitted to secondary care (i.e. hospital), a VTE risk assessment should be completed on admission. This assesses whether a patient is suitable to receive prophylactic blood thinning medication (e.g. low molecular weight heparin) to reduce risk.

Intrinsic factors

- History of DVT

- Cancer

- Obesity

- Acquired or inherited thrombophilia

- Inflammatory disorders

- Varicose veins

- Smoking

- Male sex

- Older age (> 60 years)

Transient factors

- Hospitilisation

- Recent major surgery or significant trauma

- Significant immobility (e.g. bedbound)

- Hormone therapy: combined oral contraceptive pill, hormone replacement therapy

- Long-distance sedentary travel (e.g. long-haul flights)

- Dehydration

- Acute infection

- Pregnancy (+ 6 weeks postpartum)

Pathophysiology

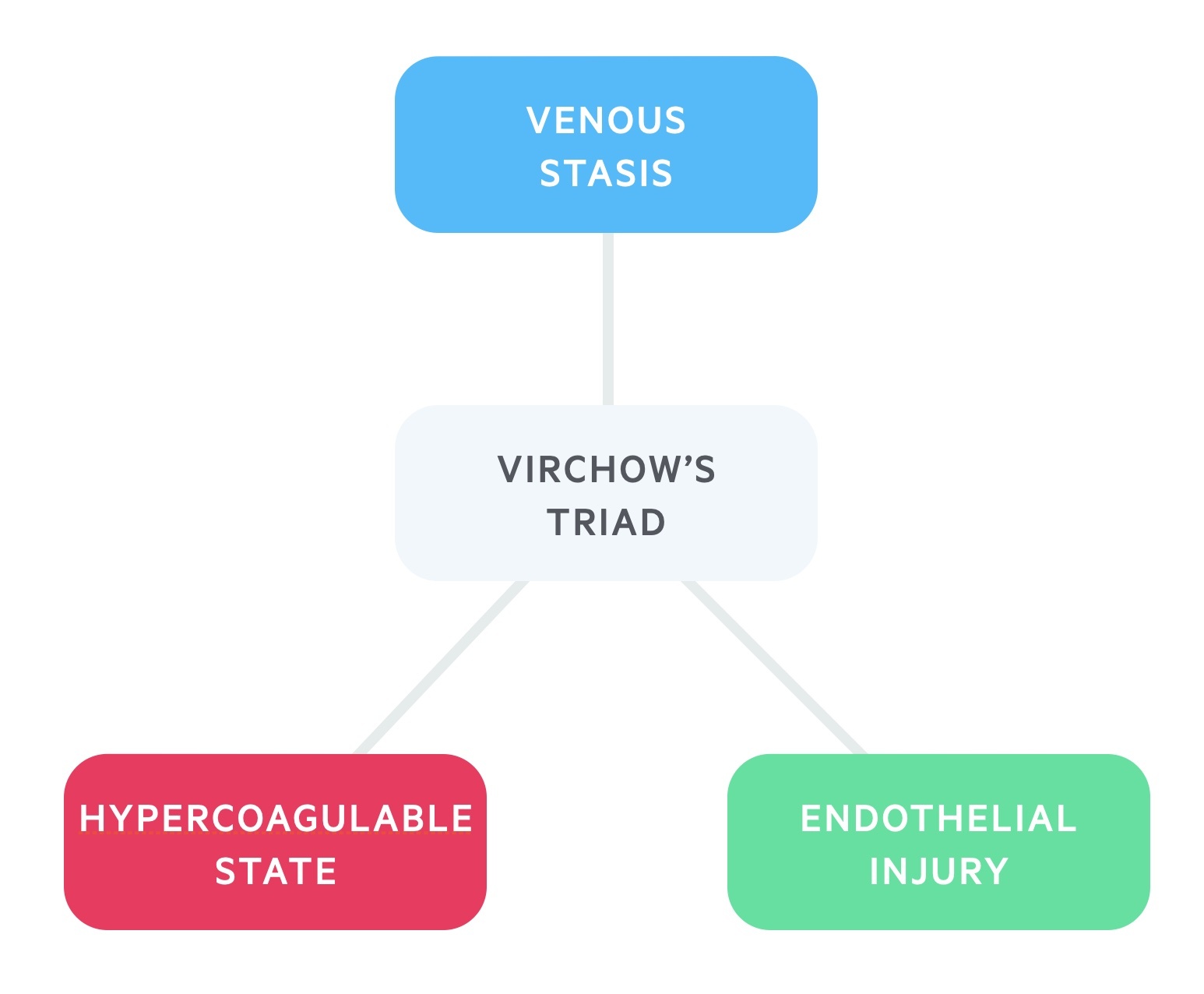

The pathophysiology of DVT is based on the principles of Virchow's triad.

The predominant theory for development of VTE is Virchow’s triad. This describes a triad of venous stasis, endothelial injury, and a hypercoagulable state. These are the three broad categories that contribute to the development of blood clots.

Patients may have inherited or acquired problems in one of more of these categories that leads to the development of blood clots. For example, a patient may have an inherited thrombophilia that increases the likelihood of clot formation or an active cancer which is associated with an acquired hypercoagulable state.

Clinical features

DVT classically presents with a painful, unilateral leg swelling that is warm to touch with surrounding erythema.

The clinical features of DVT, especially in the lower limb, may be non-specific and a significant proportion of patients will be asymptomatic. Only around one quarter of patients with PE associated with DVT are symptomatic.

Symptoms

- Unilateral leg swelling

- Pain or tenderness: particularly when walking

- Erythema

- Warmth

Signs

- Calf asymmetry: diameter > 3cm increases likelihood of DVT

- Venous distension: dilated collateral veins

- Oedema

- Tenderness along deep veins

Right lower limb DVT

Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons

Wells score & D-dimer

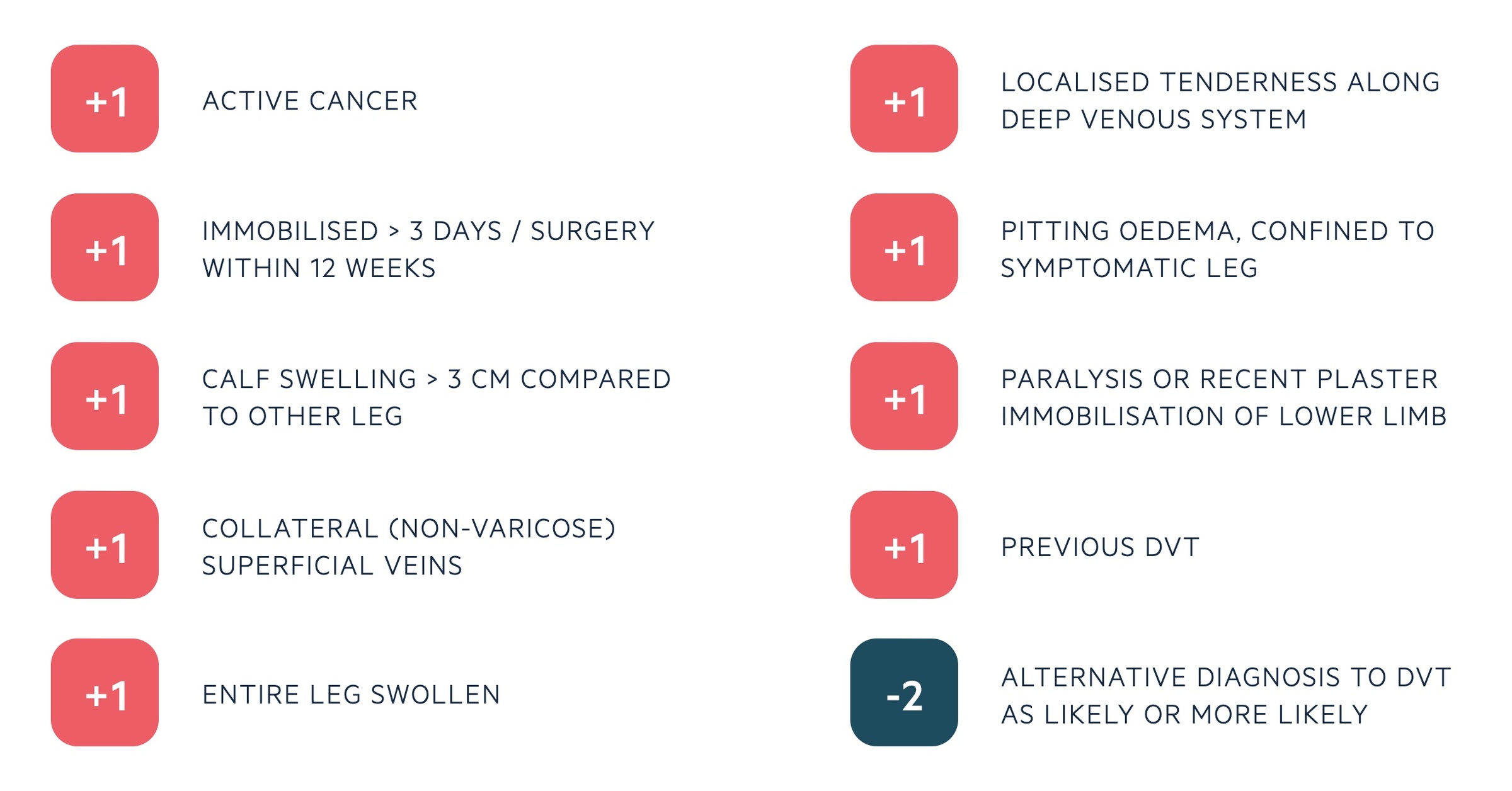

The Wells score is used to assess the likelihood, or risk, of DVT and guide further investigations.

Wells score

There are two different Wells' scores, one for the assessment of PE and one for DVT. In DVT, a series of ten criteria are used that give a score between 0-9. This divides patients into low, moderate or high risk of DVT. This score should be applied to patients felt to be at risk of DVT based on history and clinical examination.

In the two-level model, patients are grouped into two categories:

- DVT likely (score ≥ 2): straight to proximal leg vein ultrasound within 4 hours. Alternatively, request D-dimer, give interim anticoagulation and arrange ultrasound within 24 hours.

- DVT unlikely (score ≤ 1): prevalence of DVT ~5%. Proceed to d-dimer testing. If test is positive proceed to proximal leg vein ultrasound testing.

D-dimer

D-dimer is a fibrin-degradation product, which is created when blood clots are broken down by the fibrinolytic system. It is a marker of VTE but can be raised in many conditions.

It is an excellent test at ‘ruling out’ DVT due to its high sensitivity (~96%). However, it has a much lower specificity, which means there are a lot of false positives. Therefore, it cannot be used to make the diagnosis

Diagnosis

DVT is diagnosed by ultrasound evidence of a thrombus within a deep vein.

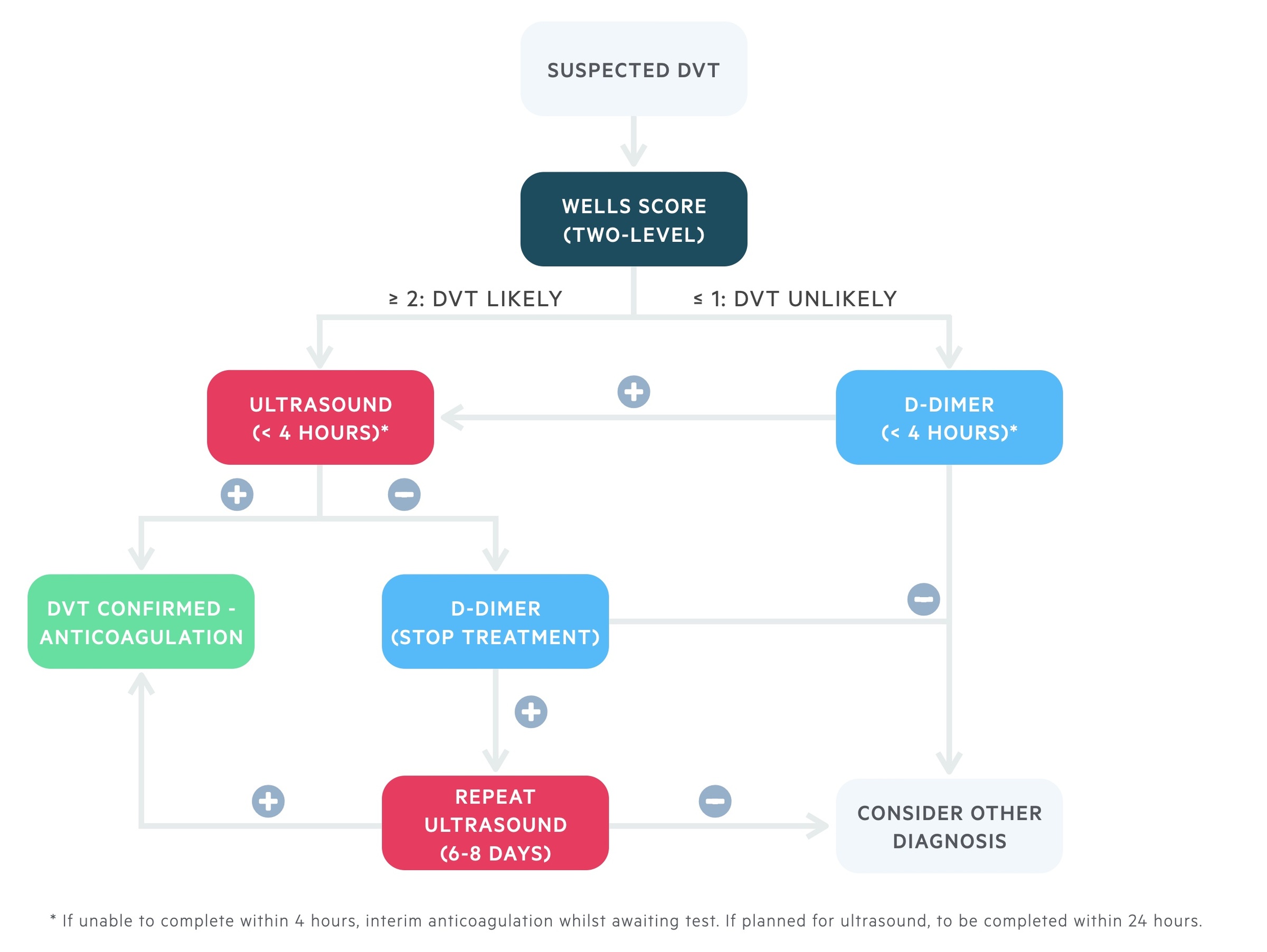

Based on the two-level Wells score. Those high risk, or low risk with a positive D-dimer, go on to have a proximal leg vein ultrasound. If a delay is expected, patients should be offered interim anticoagulation if there is no contraindication.

Patients with a positive scan are confirmed to have a DVT and offered anticoagulation. If patients have a negative scan, a d-dimer can be requested if not already completed. A negative scan and a negative d-dimer excludes DVT (consider alternative diagnosis).

If the d-dimer is positive and initial scan negative, interim anticoagulation should be stopped and patients offered a repeat proximal leg vein ultrasound in 6-8 days. This is to look for possible extension of a distal DVT into the proximal veins that requires treatment. Some centres may offer whole leg ultrasound as an alternative initial strategy. However, this is not recommended by NICE (NG158) and the data to support treatment of distal DVTs is more limited.

Other investigations

Additional investigations are required as part of the routine management of DVT (e.g. FBC, Coagulation, U&Es, LFTs) to ensure it is safe to provide ongoing prescription of anticoagulation. Investigations can also be used where an alternative diagnosis (e.g. cellulitis) or underlying cause is suspected (e.g. cancer, thrombophilia).

Anticoagulation

The are a numerous agents that can be used as anticoagulation in DVT.

The choice of anticoagulation includes low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), direct oral-acting anticoagulants (DOAC), and vitamin K antagonists (i.e. warfarin). Before confirmation of DVT, if interim anticoagulation is required patients should be offered apixaban or rivaroxaban, but LMWH is an alternative if these are not suitable.

Example choices of anticoagulation in DVT (as per NICE 2020 guidelines - NG158):

- Stable, no renal impairment or co-morbidities: offer apixaban/rivaroxaban. If not-suitable, LWMH for 5 days then offer edoxaban/warfarin*.

- Active cancer: consider DOAC (e.g. edoxaban). If not suitable, LMWH.

- Renal impairment: if creatinine clearance (CrCl) 15-50 ml/min, offer apixaban/rivaroxaban or LMWH for 5 days then edoxaban/warfarin*. If CrCl <15 ml/min offer LMWH/UFH/warfarin* as per local guidance.

*NOTE: If starting warfarin, must have two consecutive INR readings >2.0 before stopping LMWH (termed bridging therapy)

Long-term management

Patients are advised to continue anticoagulation for a minimum period of three months.

Beyond three months (3-6 months for active cancer), the duration of therapy depends on whether the DVT was provoked or unprovoked, the bleeding risk and whether the underlying risk factor has been removed. Patients should be referred to a specialist anticoagulation clinic and the risk/benefit of continuing, stopping or changing therapy discussed.

In patients with an unprovoked DVT, it is important to consider an underlying cause (e.g. inherited thrombophilia, cancer).

- Thrombophilia testing: looking for an inherited predisposition to form blood clots. Best completed by anticoagulation team*. Offered if coming off anticoagulation

- Cancer: clinical assessment and examination (including breast and testicular). Further investigations based on presence of cancer-specific clinical features (i.e. post-menopausal bleeding, breast lump).

*NOTE: Some anticoagulants can interfere with the tests carried out for thrombophilia so ideally need to be completed once off treatment.

Complications

The most concerning complication of DVT is PE, which in severe cases can lead to haemodynamic compromise and death.

The classical complication of a DVT is post-thrombotic syndrome. This describes the presence of chronic swelling, pain and skin changes from venous stasis secondary to chronic venous hypertension. In severe cases it can lead to ulcers and gangrene. It affects up to 50% of people, most commonly within two years of DVT, although there is a wide spectrum of severity.

Last updated: March 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback