Acute pericarditis

Notes

Overview

Pericarditis refers to inflammation of the lining of the heart known as the pericardium.

Inflammation of the pericardium can be acute or chronic:

- Acute pericarditis: acute-onset chest pain and characteristic ECG features (e.g. saddle ST elevation). Multiple aetiologies. Self-limiting without significant complications in 70-90% of cases.

- Chronic pericarditis: long-standing inflammation (> 3 months), usually follows acute episode. Complications include chronic pericardial effusion and constrictive pericarditis due to scarring.

Acute pericarditis is the most common pericardial disease. Although true incidence is difficult to quantify, acute pericarditis is estimated to be present in 1% of adults who present with ST elevation changes on an ECG to accident & emergency. In developed countries, acute pericarditis is most commonly secondary to a viral aetiology.

There are several terms used in the description of pericarditis and associated disorders:

- Pericarditis: inflammation of pericardial sac

- Myocarditis: inflammation of the myocardium, which is the muscular tissue of the heart

- Perimyocarditis: inflammation of both the pericardial sac and myocardium with a primarily myocarditic syndrome

- Myopericarditis: inflammation of both pericardial sac and myocardium with a primarily pericarditic syndrome

The pericardium

The serous pericardium is a double layered membrane that surrounds the heart.

Anatomy

The pericardium is composed of a tough, outer fibrous layer and an inner, serous layer. The combined thickness of these layers is 1-2mm. The fibrous pericardium is a tough sac, which completely surrounds the heart but remains unattached.

The serous pericardium is composed of two membranes that line the heart. These are the parietal and visceral pericardium. Between these two membranes is a small volume of fluid.

- Parietal pericardium: internal surface of the fibrous pericardium

- Visceral pericardium: inner membrane, known as the 'epicardium', which covers the heart and great vessels

- Pericardial space: contains a small amount of serous fluid (20-50 mls)

Physiology

The pericardium has three main physiological functions:

- Mechanical: limits cardiac dilation, maintains ventricular compliance (i.e. relationship between volume and pressure), and aids atrial filling.

- Barrier: reduces external friction and acts as a barrier.

- Anatomical: fixes the heart through its ligamentous function.

Aetiology & pathophysiology

In developed countries, the majority of cases are due to a transient viral infection.

In most cases of acute pericarditis, the pericardial sac is acutely inflamed with infiltration of immune cells secondary to an acute infection or as manifestation of a systemic disease.

The aetiology of acute pericarditis is numerous:

- Idiopathic: significant proportion of cases are idiopathic. Majority thought to represent undiagnosed viral infections. Clinically, unable to distinguish between viral and true idiopathic pericarditis.

- Viral: most common. 1-10% of cases. Short-lived lasting 1-3 weeks. Often due to coxsackievirus B. Variety of other viruses implicated (e.g. influenza, echovirus, adenoviruses, enterovirus, etc)

- Bacterial: approximately 1-8% of cases. May occur due to haematogenous spread, extension from pulmonary infection or as complication of endocarditis or trauma. Multiple organism implicated including gram positive and negative.

- Tuberculosis: must be investigated in high prevalence areas or high-risk patients (e.g. immunodeficiency). 4% of all cases. More insidious onset. High-risk of chronic pericarditis and constrictive complications.

- Systemic disease: underlying systemic inflammatory disease (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis). Features of systemic disease on clinical assessment. May complicate chronic kidney disease (e.g. uraemic pericarditis), hypothyroidism or post-myocardial infarction

- Other: drugs, radiotherapy and trauma

Due to the usually benign disease course associated with a viral infection, an in-depth search for an underlying aetiology is not necessary in most cases. The need for inpatient admission and further investigations is guided by the likelihood of an underlying disorder on initial assessment and the presence of prognostic risk factors (discussed below).

Dressler’s syndrome

This is a specific autoimmune form of acute pericarditis that occurs 2-3 weeks following a myocardial infarction.

Unlike the immediate post-myocardial infarction pericarditis due to direct inflammation from transmural infarction, Dressler’s syndrome is thought to be an autoimmune reaction to myocardial antigens post infarction.

Prognostic risk factors

These are factors associated with a worse prognosis and warrant search for an underlying aetiology and inpatient admission.

As discussed, the majority of cases are due to a viral infection and a relatively benign course. However, in the presence of major of minor risk factors, patients require inpatient admission and search for an underlying aetiology.

Major risk factors:

- Fever > 38º

- Subacute onset

- Large pericardial effusion

- Cardiac tamponade

- Poor response to 1 week of treatment

Minor risk factors:

- Myopericarditis

- Immunosuppression

- Trauma

- Oral anticoagulant therapy

Clinical features

The cardinal feature of acute pericarditis is chest pain.

Symptoms

- Chest pain: sharp, pleuritic (worse on inspiration). Characteristically better on leaning forward and sitting up

- Fever: usually low-grade

- Breathlessness: may indicate development of complications such as pericardial effusion or myocardial involvement.

- Cough

Signs

- Pericardial friction rub: scratchy or squeaking sound heard over the heart

- Features of cardiac tamponade: muffled heart sounds, distended JVP, pulsus paradoxus (fall in blood pressure > 10 mmHg during inspiration), hypotension

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is usually based on a typical history, characteristic ECG findings and exclusion of other causes.

Formal diagnosis of acute pericarditis is based on finding two of the following four features:

- Typical chest pain

- Pericardial friction rub

- Characteristic ECG features

- New or worsening pericardial effusion

NOTE: based on 2015 European Society of Cardiology guidelines on pericardial disease

Investigations

Patients with suspected acute pericarditis require formal assessment, blood tests, ECG, CXR and echocardiogram.

Blood tests

- FBC

- U&Es

- CRP

- Troponin: if elevated, suggests myocardial involvement (i.e. myopericarditis)

Selective blood tests may be completed based on suspected aetiology. These include cultures, virology, autoimmune screen or tuberculosis work-up.

ECG

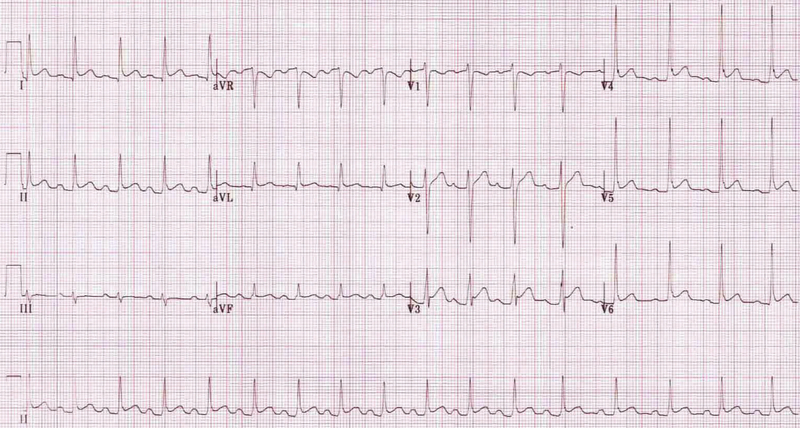

The characteristic ECG findings are widespread saddle-shaped ST elevation with PR depression.

ECG showing widespread saddle-shaped ST elevation

Image courtesy of Popfossa

Most cases show ST elevation in both limb and chest leads. May be difficult to distinguish from myocardial infarction or benign repolarisation. T wave changes and q waves rarely seen in acute pericarditis, which would favour myocardial infarction. Reciprocal ST depression sometimes seen in aVR and V1 as shown in ECG above.

Chest x-ray

Useful to exclude an alternative diagnosis in any patient presenting with chest pain. In addition, helps exclude pneumonia if raised inflammatory markers. May show enlarged cardiac shadow if significant pericardial effusion.

Echocardiogram

In acute pericarditis, typically normal. Essential in patients with suspected pericardial effusion as helps to quantify amount and assess for any haemodynamic compromise of cardiac function.

Useful if concern regarding myocardial infarction or myocardial involvement. Able to look for any regional wall motion abnormalities that represent focal areas of myocardial dysfunction due to myocarditis or ischaemia.

Other

Cardiac MRI and CT may be needed in specific cases. Cardiac MRI is useful for the assessment of myocardial involvement. CT is useful at assessment of surrounding pulmonary and pleural structures that may suggest a specific underlying cause (e.g. tuberculosis).

Management

The mainstay of treatment for acute pericarditis is the use of NSAIDs, aspirin or colchicine.

In cases of idiopathic/viral acute pericarditis, the treatment involves NSAIDs/Aspirin +/- colchicine.

- First-line: ibuprofen (600 mg TDS) or aspirin (600 mg TDS). Ensure no contraindications. Give for 1-2 weeks until pain resolves. Tapering advised. Gastric protection (e.g. proton pump inhibitor).

- Adjuvant: colchicine (2-3 mg loading then 0.5 mg BD) can be given as an adjunct to NSAID treatment or as primary therapy in patients with contraindications. Typically longer course (i.e. 3 months)

- Other: short courses of oral corticosteroids may be required in patients who fail to respond, those with contraindications or development of side-effects.

Specific causes of acute pericarditis should be treated according to the underlying disease. Medications above may be used in addition to definitive treatment.

Patients without major/minor risk factors or a suspected underlying aetiology can be managed as outpatients. Important to advise on restriction of physical activity until symptoms resolve or diagnostic tests (e.g. CRP/ECG) improve. In athletes, further minimal restriction of physical activity advised for three months.

Complications

The majority of patients with acute pericarditis make a good recovery.

In idiopathic/viral pericarditis, around 15-30% of patients without treatment will develop recurrent disease. Incessant (pericarditis for 4-6 weeks) and recurrent (repeated acute episodes) pericarditis can be problematic.

Rare, but serious, complications of acute pericarditis include cardiac tamponade and chronic pericarditis.

- Cardiac tamponade: compression of the heart by pericardial fluid, which can lead to cardiovascular collapse and cardiac arrest. Requires urgent pericardial paracentesis. Rarely occurs in viral/idiopathic acute pericarditis

- Chronic pericarditis: chronic inflammation of the pericardial sac and high-risk for developing constrictive pericarditis. Around 1% risk of constrictive pericarditis from idiopathic/viral aetiology compared to 20-30% for bacterial aetiology including TB.

Last updated: March 2022

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback